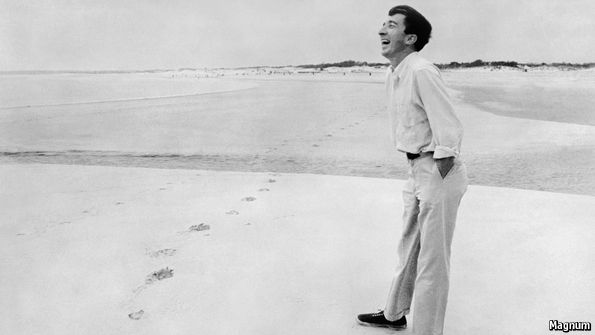

John Updike doesn't create characters, just neurosis. That’s what I remember a dinner partner saying a while ago after we finished our deserts and now chatted away the remaining interests we shared. She was not a fan of novelist John Updike. I begged to differ, responding as follows, in a paraphrase of the actual words: Perhaps, but Updike has written much better novels. He's had his share of duds, but an unusually high proportion of his work is masterful, even brilliant. The Rabbit quartet, The Coup, Witches of Eastwick, Brazil, Beck: A Book, The Centaur, Roger's Version. I could go on. It's interesting, too, to note the high incidence of experimentation with narrative form and subject matter. Rabbit placed him with this image of being someone comically dwelling on the lapsed virtues of middle-aged East Coasters, ala John Cheever, (another writer I prize), but he has been all over the map so far as what he's written about and how he wrote about it. The career-long chronicling of men who thought they were driven by a superior purpose and moral clarity only to find themselves undermined by hunger, itches, instincts and unarticulated libidos remain, I think, one of the great accomplishments of American writing. Although I've cooled on Updike lately--I've been reading him for thirty years--I can't dismiss him nor diminish his accomplishment. He is one of the untouchables. Besides, neurosis is character, and it's hardly a monochromatic shade. It's a trait that comes across in infinitely varied expressions, and we need someone who can artfully exploit their potential.

John Updike doesn't create characters, just neurosis. That’s what I remember a dinner partner saying a while ago after we finished our deserts and now chatted away the remaining interests we shared. She was not a fan of novelist John Updike. I begged to differ, responding as follows, in a paraphrase of the actual words: Perhaps, but Updike has written much better novels. He's had his share of duds, but an unusually high proportion of his work is masterful, even brilliant. The Rabbit quartet, The Coup, Witches of Eastwick, Brazil, Beck: A Book, The Centaur, Roger's Version. I could go on. It's interesting, too, to note the high incidence of experimentation with narrative form and subject matter. Rabbit placed him with this image of being someone comically dwelling on the lapsed virtues of middle-aged East Coasters, ala John Cheever, (another writer I prize), but he has been all over the map so far as what he's written about and how he wrote about it. The career-long chronicling of men who thought they were driven by a superior purpose and moral clarity only to find themselves undermined by hunger, itches, instincts and unarticulated libidos remain, I think, one of the great accomplishments of American writing. Although I've cooled on Updike lately--I've been reading him for thirty years--I can't dismiss him nor diminish his accomplishment. He is one of the untouchables. Besides, neurosis is character, and it's hardly a monochromatic shade. It's a trait that comes across in infinitely varied expressions, and we need someone who can artfully exploit their potential.

HOW MANY PALTRY, FOOLISH, PAINTED THINGS

(Michael Drayton, 1563-1631)

How many paltry foolish painted things,That now in coaches trouble every street,Shall be forgotten, whom no poet sings,Ere they be well wrapped in their winding-sheet!Where I to thee eternity shall give,When nothing else remaineth of these days,And queens hereafter shall be glad to liveUpon the alms of thy superfluous praise.Virgins and matrons, reading these my rhymes,Shall be so much delighted with thy storyThat they shall grieve they lived not in these times,To have seen thee, their sex’s only glory:So shalt thou fly above the vulgar throng,Still to survive in my immortal song.

Michael Drayton’s ode speaks to posterity, speaking to what he believes is the likelihood that this fair woman will be remembered, gloried and virtually worshipped as womanly perfection in ages yet to come by virtue of his poem. The ladies who now clutter the streets “shall be forgotten” by poets and this miss will be the envy of women of future elegant pretense because Drayton’s directly addressed ideal is “their sex’s only glory”. A harsh judgment, but it plays to vanity and a person’s feeling of being unjustly ignored. There is resentment here to be exploited and Drayton’s technique, effective or not, is a masterful piece of exploitation. It takes a man, after all, to make the world aware of the genius of the woman who has taken his arm in companionship, in romance, in matrimony. The woman is anonymous, a cipher without the right man to make the powers that are innate in her bosom radiate fiercely, proudly, for the world to praise and to cater to. “So shalt thou fly above the vulgar throng,/Still to survive in my immortal song.” This is to cleverly say that the woman will be remembered forever because of the man’s immortal song, which is also to say that only a man, this man, could have written. Without the man’s words, his voice, the woman being seduced is unknown, without the power he extols in the lyric, which is to say that she is without her own voice, bereft of even a language to command. rather classically, both these quick-witted sonnets display less the feeling of spontaneity, of genuine play, than they do the feeling of a well-constructed presentation, an argument mulled over, finessed and converted into a poeticized template intended for the means of endearing oneself to women by appealing to their perceived vanity. This makes you consider the old cartoon line when Olive Oyle says to Popeye and Bluto, as they try to woo her, “I bet you say that to all the girls.” The speakers, the wooers, the orators that profess the unqualified beauty, brilliance, charm, grace, and sublimity of their objects of affection, deliver their testimonies with it in mind to present themselves in an exceptional light; the sonnets are, in essence, sales pitches, imbuing the speakers with qualities compatible with the ones they’ve ascribed to their ladies dearest without so much as one self-glorified personal pronoun being used in either of these artfully cantilevered proclamations. It’s a subtle argument to be made that requires the most skillful of tongues, that the qualities , the talents that are being attached to the would be betrothed have not been noticed by the the rabble, the masses, those who live a generic existence, and that only the men who have broached and spoke to the subject of the ladies beauty are intelligent, sensitive, caring, dynamic enough to speak these truths. It is artful indeed, requiring a fine a balance, of knowing when to let one’s voice trail off, to end on a soft syllable, awaiting a response. This is bragging through the flattering of another.I rather like the wit and spare and adroit verbal sharpness that mark both of these poems; graceful, preening, softly boasting and flattering the women to whom they are addressed in terms that bestow qualities exceptional, unique, miraculous to behold, these are the testimonies of horn dogs working their way into a woman’s favor. And, perhaps, the respective beds they sleep. in.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1985647-1351980780-7019.jpeg.jpg)

the scarecrow in the distant field

holding onto its flapping coat

saying, "Don't forget me!"

That quiet at midnight,

the slow giving in

to each other--something

moving at the window again, then gone.

This reads like the Disney version of "The Legend of Sleepy Hallow", at best, all in what seems like an attempt to mine what one feels is an inexhaustible font of material, their emotions. Emotions that are, it seems, always sad, as if required by some unspoken Poet's Guild that the collective persona of bards must be a population beset by an exaggerated sensitivity to life's barrage of an existence that seems to disregard our feelings , passions and pet peeves.