Discussing Little Feat, music critic Robert Christgau ventured to say that the dedicated group wasn't just another jam band from Los Angeles but were, in disguise, Euro progressive-rockers at heart. Little Feat had slide guitar, soulful vocals, and boogie well enough to satisfy anyway speedway inclination to get in the T Bird and gun your engine. Still, Bill Payne's slippery keyboard work's modernist jazzy and sly sound and the sneaky switching of time signatures amid the funk-riffing improvisation, and odd and provocative melange of jazz, blues, rock and soul influences, made them hard to classify. Christgau pegged them as a brighter version of the Continental art-rockers. Plainly, Little Feat wanted their music to be something that reflected the best use of their musicianship. Their sound was skilled, never busy, lyrically evasive and evocative at the same time, never far the American mythos of Robert Johnson country-blues or Bukowski/Selby/Algren take on seeking transcendence as well as survival in a post-war American city.

To Christgau's point, I would add Steely Dan, perhaps the most inscrutable band to achieve a long line of radio hits, platinum albums, and sold-out tours. More so than Little Feat, Steely Dan was incredibly sharp at composing great hooks for their songs, those brief introductions at the start of tunes or coming midway during the chorus, or appearing else, unanticipated, that lures you into the story and the musical moods that underscore the emotional journey. Beyond hooks, though, Steely Dan was eclectic in the styles they drew from inputting their albums together--great bouts of guitar boogie for the stadium crowd, a mid-tempo bottom of jamming funk keeping matters on a constant low boil, Ellington like tone poems where the horn players managed brass and reed orchestrations only to give way to alone, searching cry and lilt of sax improvisation.

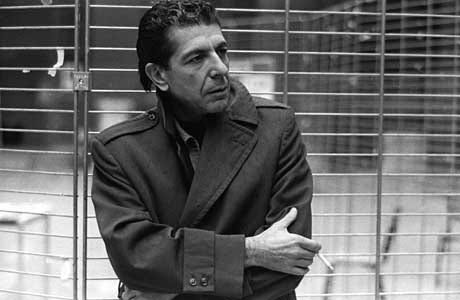

All this and the hooks, and the lyrics, managed by keyboardist and lead vocalist Don Fagin, an opaquely and vaguely presented universe of people, places, things, and situations that rarely come into sharp focus; surreal, witty, allusive, cruel, and kind in different turns of mood, Fagin didn't have a large world he wrote about, or instead, wrote around. But his wordcraft was generally superb, like the music, artful but not crowded, bright but chatty. The recently deceased Walter Becker, dead at age 67, Steely Dan co-founder with Fagin, a writing partner in a beautifully realized team effort, made this work all of the pieces. He arranged the music, turning mere hooks and stray ideas into whole pieces.

As often as not, centering an arrangement around Fagin's keyboard, with its affection for minor-key flirtations at the end of chord progressions that just as often seemed like an awakening and eventual arousal from the dream you wish you could return to. Becker's work on the arrangements showed that he knew how to extend and compress sections of a song under construction. His was the ability to have their best material to be immediate clarity of riff, flourish and hook. He had a discerning ear for things more diffuse, abstract, opaque informal response to emotional states under an artist's scrutiny, made Steely Dan unique even in a time when there was scarcely a shortage of quality musicians and experimenters advancing their way to their respective versions of true and only heaven.

Add to this surrealistically pleasurable slurring of motifs, literary conceits, and hard-bop resolve. We have Becker's signature guitar work, stinging, serpentine solos, short fills, and spatially sublime solos with phrasing that seemed to move in a coiling, sideways motion. Becker was never in a hurry with his fretwork; his note choices investigated the chords and space between them, popped, stung, and soothed as motif and mood required. Becker co-created something priceless, alluring, daunting, yet readily approachable in pop music. It's a pity there is no real equivalent prize such as the Nobel for rock and roll.