|

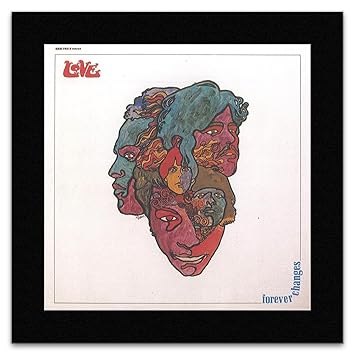

| FOREVER CHANGES--Love |

I caught

wind that 2017 would be the fiftieth anniversary of the release of Love's

seminal record, Forever Changes—an occasion I could not let glide

past without a dutiful, a tribute, listen to the revered 1967 album. I was

mesmerized all over again by a shimmering range of materials: an acidic rock

guitar, martial rhythms, sad, almost mocking Mariachi horn sorties, a Spanish

guitar and tango beats, lush arrangements, MOR pop-jazz, and the cunning skill

to write the sort of private lyric that drew the listener closer to the

speaker, thirsting for the words, yet cruelly denying a comforting, a vulgar,

assurance.

There were

menacing undercurrents beneath the fleeting elegance, an album full of wide

roads, sharp terms, and an almost unbearable, idyllic optimism. It was as if

Arthur Lee, that vibrant vocalist and principal songwriter, had absorbed every

note of music—from every style that poured, a glittering sludge, from Los

Angeles radio—blending them with a master’s will, providing a true, an original

thing, something no one had, in all probability, ever heard before. It remains

a fascinating and dramatic document; it’s damn good music. The way this disc

moves, a chameleon on a plaid fabric, from one mood to the next, quickly but

not jarringly, from upbeat, dance-happy jazz to the serene yet melancholic

textures, shades, and tonalities the orchestrations create as they play over

the solid rock band base, remains amazing and, I think, utterly unequaled.

The Beatles

were antecedents, of course, in their clever employ of diverse musical styles

in their songs, mixing them up in ways rock and roll songwriters hadn't

imagined up to that time. But a major element of Lee's and Love's success in

diving headlong into that choppy eclecticism was a certain fastidiousness, an

avoidance of the limitless disasters of others who attempted their own, clumsy

versions of Sgt. Pepper.

Not all the

music on Forever Changes has aged well, alas. Lee’s lyrics

sometimes become a murmuring stream of hippie know-nothingism—a kind of

spiritual slumming. The guitar solos, though mercifully brief, are likewise

cringe-inducing, those atonal fuzz tone blasts that sour the album’s otherwise

sublime arrangements. Where, one wonders, were Hendrix and Clapton when their

savvy on the frets was so desperately needed?

All told,

this is only a nitpicking, a minor quibble, a footnote to genius. The record is

of its time and still creates a spell fifty years later. Arthur Lee was one of

the greatest of rock singers as well, an ironic commentary on identity

politics; we see this in his beautiful crooner style, which echoes the

under-considered talent of Johnny Mathis and Sammy Davis Jr., two pioneering

black performers who honed singing styles that were smooth, gallant, and

perfectly acceptable to large white audiences. We also see it in the way Lee

mastered the grunting, gravelly, slurring style of British singers like Mick

Jagger and Eric Burdon—two singers who tried to replicate the sound of their

heroes Muddy Waters and Howling Wolf but who, lacking the true vocal apparatus,

wound up creating a style of singing that was itself appealing and a valid

means of personal expression. Lee was equally smitten with both styles and

mingled them throughout his oeuvre; the silky croon and gruff belt combined for

an unexpected effect, mysterious and suggestively unique.

Two songs

particularly have remained with me these fifty years since I first heard this

record, melodies, chords, and winsome vocals that echo still amidst the

accumulated memories: the opening song, and the album's final song. The first,

written by the guitarist and singer Bryan MacLean, is the exquisitely flawless

"Alone Again Or." It begins faintly, a ghost of sound, volume slowly

increasing, a Spanish guitar and a sharp, insistent report of a small drum kit,

simple and elegantly finger-picked chords that bring us a confession of a kind,

a soul reaching out to a lover who leaves him alone in his isolation. The

second verse is a declaration, a statement of personal purpose:

"I

heard a funny thing /somebody said to me /you know that I could be in love with

almost everyone, I think that people are/The greatest fun…."

As the

melody charges, segues into a stirring horn solo and again fades off and then

builds momentum, we have the genius of the album, a mix of insight and naivete

trying to balance them out, contained in a gorgeous, simple framework.

MacLean's forlorn disquisition is about the battle of a man trying to bring

clarity to the many sensations his senses brought him. Each day a new hope,

every afternoon the same confusions of elation and sadness, each night a

solitude that embraces the narrator as fully as the sleep that will come over

him and so prepare him for the morning.

The album's

last tune, Lee’s masterpiece, is "You Set the Scene," a fascinating

stitchery of the kind of rush discotheque pulse where everything is noticed and

reality becomes a druggy collage. Details are word fragments, phrases, and

images that do not follow each other in a logical order; it is as good a

description of an acid trip as I’ve listened to. The trippy pulse of the first

section segues into the steady, marching stride of the second portion. Horns

blare a hearkening fanfare, drums kick in with a steady, even gait, and the

narrator seems to have crashed from his high after a vision and now allows his

eyes to scour the hillsides and valleys and consider, finally, the kind of

future he’d like to live in.

"Everything

I've seen needs rearranging /And for anyone who thinks it's strange/Then you

should be the first to want to make this change/And for everyone who thinks

that life is just a game/Do you like the part you're playing?"

Yes, this

smacks of the old counterculture conceits, the young man, smitten with The

Truth, saying farewell to parents and old friends to become genuinely

authentic. But Lee’s imagination prevents this from becoming a preposterous

demonstration. Lee’s voice soars, croons, quivers, strains effectively on high

notes, floating with confidence over the increasingly dynamic horn arrangement.

This is a march into the future; it astonishes me how magnificent this music

still sounds fifty years on. Forever Changes, Love's third album,

is considered by many to be the best American response to the Beatles'

bar-raising disc Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. As is too

often the case, Lee’s greatest creative period was short-lived; drugs, jail,

eccentricity, and erratic behavior prevented him from regaining the heights he

reached with Forever Changes.