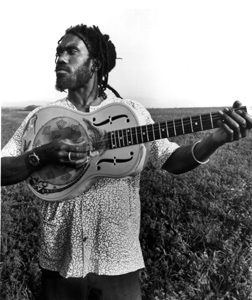

Corey Harris, a fine blues guitarist, songwriter, and singer in a neo-traditionalist blues style, writes a provocative column on his blog Blues is Black Music entitled "Can White People Sing the Blues?" Harris, a musician, specializing in a style of blues that's been around much longer than his years on this earth, insists it's an important question. His primary objection of whites playing what is a black art form is this: that while listeners are entertained by technical competence and show business bedazzlement, they do not have legitimacy because the music is robbed of historical context and is, as a result, merely ornamentation, not art that convincingly interprets personal and collective experience in a cruel, problematic existence. There is no culture without the long, collective memory to inform it and keep it honest.

" Without culture there is no music. Music is the voice of a culture. Separate the two and the music can never be the same. Of course, it may be in the same style as the original, but the meaning of a song such as Son House's 'My Black Mama' will always be changed with a different performer. This is especially true if the performer is not from the Black culture that gave birth to the blues."

I agree that those aspiring to perform blues, jazz, or soul

should forever know what they are picking up is black music created by and

defined by black artists and the culture, twisted as it may have been,

that contained the forces that brought together elements of African and

European tradition that otherwise would not have met. Would that the

institutions that created the genius of African American music hadn't been the

racist and economically determinist demon of Slavery? Harris, though, assumes

that culture is static and implies that black culture has remained still. The

creation of Black American culture regarding art, education,

literature, music, theatre, speech, theology refutes that rather handily, as it

arises, through forced circumstances, from a system of oppression; oppressed

classes create counter-institutions.

The new black culture gradually arose and developed as the response by black

communities to the decimation of the institutional, social and spiritual

traditions that had been theirs in their own land. The new culture, in turn, influenced

the larger culture, the culture of white people. One can single out exploitation,

minstrelsy, racist practices, blatantly bad, and watered-down imitations of

popular and emerging black art forms, especially musical idioms. Still, there

is the area of the personal, localized, and influence of blues culture on white

musicians apart from record companies, promoters, and agents where the younger

musician is influenced and, in effect, being mentored by the Black

musicians they admired took their cues from. Harris makes a powerful

argument based on a series of cherry-picked conceits to the exclusion

of glaring contradictions. He speaks that the metaphysical essence of blues is

feeling, emotion, the ability of the human voice to convey true experience, and

yet he speaks in racial absolutes, denying the capacity of individual musicians,

black and white, to transcend, mature, grow out of the imitative phase and

achieve a true feeling, a true vision of the music they love. The case is that while self-righteous revisionist scolds like

Harris is articulate will limit the range of blues to exclude all who are not

black from having true blues authenticity, art does not sustain itself by

remaining in a vacuum. No matter how righteous the music's argument belongs to,

without the constant input from musicians attracted to it and performing it according

to the narrative of their personal lives, the music ceases to grow. It shrivels

up and dies and becomes only a relic, notable mostly for its distant and

antiquated sound.

We will admit without reservation, upfront and unconditionally, that blues and jazz are Black-American creations. It's important to keep that fact in mind. Still, the blues, being music, is something that catches the ear of the blues lover, regardless of race, and speaks to those people in profound ways, giving expression to perceptions, emotions, personal contradictions in ways that mere intellectual endeavor cannot; it is this music these folks come to love, and many aspire to play, to make their own and stamp with their own personality and twists and quirks. That is how art, any art, survives, grows, remains relevant enough for the born-again righteousness of Harris to reshuffle a less interesting set of arguments from LeRoi Jones' book "Blues People."

There is the aspect that blues is something in which anyone one

can play the game, an element that exists in any instance of art one thinks

ought to be restricted to particular groups, but what really matters

is less how many musicians have gotten in on the game as much as how many are

still on the playing field over the years, with great tunes, memorable

performances, slick licks, and most importantly, emotions that are

real, emphatic, unmistakable. There is no music without real emotion and new

inspiration from younger players bringing their own version of the wide and

dispersed American narrative to the idiom. There is no art, and it dies, falls

into irrelevancy, and is forgotten altogether.