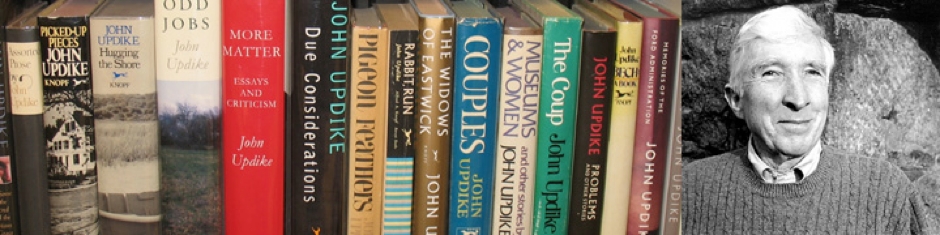

It's been said that John Updike is able to write extremely well about nothing what so ever, less to do with the sort of hyper-realism of Robbe-Grillet or the purposeful taxonomies of David Foster Wallace than the plain old conceit of being in love your own voice. There is no theoretical edge to Updike's unceasing albeit elegant wordiness. It's a habit formed from deadlines as he authored many books of short stores, published novels at a steady click, and wrote high caliber book and art reviews in great quantity. He was a writer by trade, and write he did . He has published a minimum of one book a year since his first book The Poorhouse Fair was published in 1958, and like any artists who is as prolific over a long period--Wood Allen and Joyce Carol Oates fans take note--there will be the inevitable productions that are ambitious but under constructed, dull, repetitive of past success, what have you.Toward the End of Time was one of his occasional flings with science fiction and it was dull beyond repair. Licks of Love was rather a quaint and grandiloquent selection of lately composed stories that don't add much to his reputation. The Rabbit quartet, though, is masterful, a genuine American Saga of a man who is the quintessential rudderless citizen who goes through an entire lifetime in which none of his experiences gives any clue to purposes beyond his own disappointments and satisfactions. Updike is brilliant in this sequence, and for this alone I'd guess his reputation as a major writer is safe for generations to come. He's had his share of duds, but an unusually high proportion of his work is masterful, even brilliant. The Rabbit quartet, The Coup, Witches of Eastwick, Brazil, Beck: A Book, The Centaur, Roger's Version. I could go on. It's interesting as well to note the high incidence of experimentation with narrative form and subject matter. Rabbit placed him with this image of being someone comically dwelling on the lapsed virtues of middle aged East Coasters, ala John Cheever, (another writer I prize), but he has been all over the map so far as what he's written about and how he wrote about it. Even though I've cooled on Updike lately--I've been reading him for thirty years--I can't dismiss him nor diminish his accomplishment. He is one of the untouchables. Besides, neurosis is character, and it's hardly a monochromatic shade. It's a trait that comes across in infinitely varied expressions, and we need someone who can artfully exploit their potential.

Showing posts with label John Updike. Show all posts

Showing posts with label John Updike. Show all posts

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Thursday, August 30, 2018

THE MIRROR MAN

John Updike doesn't create characters, just neurosis. That’s what I remember a dinner partner saying a while ago after we finished our deserts and now chatted away the remaining interests we shared. She was not a fan of novelist John Updike. I begged to differ, responding as follows, in a paraphrase of the actual words: Perhaps, but Updike has written much better novels. He's had his share of duds, but an unusually high proportion of his work is masterful, even brilliant. The Rabbit quartet, The Coup, Witches of Eastwick, Brazil, Beck: A Book, The Centaur, Roger's Version. I could go on. It's interesting, too, to note the high incidence of experimentation with narrative form and subject matter. Rabbit placed him with this image of being someone comically dwelling on the lapsed virtues of middle-aged East Coasters, ala John Cheever, (another writer I prize), but he has been all over the map so far as what he's written about and how he wrote about it. The career-long chronicling of men who thought they were driven by a superior purpose and moral clarity only to find themselves undermined by hunger, itches, instincts and unarticulated libidos remain, I think, one of the great accomplishments of American writing. Although I've cooled on Updike lately--I've been reading him for thirty years--I can't dismiss him nor diminish his accomplishment. He is one of the untouchables. Besides, neurosis is character, and it's hardly a monochromatic shade. It's a trait that comes across in infinitely varied expressions, and we need someone who can artfully exploit their potential.

John Updike doesn't create characters, just neurosis. That’s what I remember a dinner partner saying a while ago after we finished our deserts and now chatted away the remaining interests we shared. She was not a fan of novelist John Updike. I begged to differ, responding as follows, in a paraphrase of the actual words: Perhaps, but Updike has written much better novels. He's had his share of duds, but an unusually high proportion of his work is masterful, even brilliant. The Rabbit quartet, The Coup, Witches of Eastwick, Brazil, Beck: A Book, The Centaur, Roger's Version. I could go on. It's interesting, too, to note the high incidence of experimentation with narrative form and subject matter. Rabbit placed him with this image of being someone comically dwelling on the lapsed virtues of middle-aged East Coasters, ala John Cheever, (another writer I prize), but he has been all over the map so far as what he's written about and how he wrote about it. The career-long chronicling of men who thought they were driven by a superior purpose and moral clarity only to find themselves undermined by hunger, itches, instincts and unarticulated libidos remain, I think, one of the great accomplishments of American writing. Although I've cooled on Updike lately--I've been reading him for thirty years--I can't dismiss him nor diminish his accomplishment. He is one of the untouchables. Besides, neurosis is character, and it's hardly a monochromatic shade. It's a trait that comes across in infinitely varied expressions, and we need someone who can artfully exploit their potential. Friday, March 16, 2018

Updike

Novelist Dianna Evans writes a fine essay regarding the late John Updike's decline in reputation as a novelist due, mostly, to his over all failure to create fully-formed women characters. Her response is ambivalent, understandably so, as Updike could be mean to his women characters, and yet he wrote so beautifully, lyrically, ingratiatingly. No surprise the late novelist John Updike isn't a favorite among younger readers in this era of "Me Too" and "Times Up". Indeed, the age of men being held accountable for their conduct has come and it's here to stay. A good thing.

Updike was not especially kind in his depictions of women in his fiction, and for that he needs to read critically, but one needs to admire his stated understanding of what his duty as an artist was,"“My duty as a writer is to make the best record I can of life as I understand it,and that duty takes precedence for me over all these other considerations.” The novelist and short story writer wrote elegantly, lyrically, poetically, he had , perhaps, the most perfect prose style of any American writer of his generation, and he created a fictional world of men, mostly heterosexual , fumbling through the lives full of small stakes ambition and fully licensed libidos that derailed their best natures with compromises of opportunism, affairs, self deception, an inability to see larger contexts beyond their perspectives.

The writer was , like many of his characters, unable to see further than his own vision, an aspect that might be called a great writer's failure of imagination,but what he did know he know--a straight , middle class male's world of materialism and lust rationalized into metaphysical permanence--he understood intimately, knowingly, and was aware of how the limits makes perfect plans, perfect plans, fall apart or produce results contrary to expectations. Updike wasn't, I don't think, quite so oblivious to his renderings of women in his tales, but I think his aim, over all, was to imaginatively construct the many scenarios of how the perfect worlds of his protagonists are at odds with a universe that will not obey good or bad intentions. That he wrote about this world so beautifully--there are those times when I pick up an Updike book, say "Rabbit Run" or "The Centaur" or "The Witches of Eastwick" just to have the language figuratively roll of the page as if the words , the sentences or the fleeting notes of a transcendent Clifford Brown solo-- might be a flaw in his art, one could argue.

He makes it attractive, the prose is a seduction of a kind. Fine, that makes him dangerous for both male and women writers, which makes him artist, a great one. That makes him a pleasure to read and a pleasure worth discussing critically, as a means of understanding our own responses to his increasingly problem-making, if still alluring works,

Updike was not especially kind in his depictions of women in his fiction, and for that he needs to read critically, but one needs to admire his stated understanding of what his duty as an artist was,"“My duty as a writer is to make the best record I can of life as I understand it,and that duty takes precedence for me over all these other considerations.” The novelist and short story writer wrote elegantly, lyrically, poetically, he had , perhaps, the most perfect prose style of any American writer of his generation, and he created a fictional world of men, mostly heterosexual , fumbling through the lives full of small stakes ambition and fully licensed libidos that derailed their best natures with compromises of opportunism, affairs, self deception, an inability to see larger contexts beyond their perspectives.

The writer was , like many of his characters, unable to see further than his own vision, an aspect that might be called a great writer's failure of imagination,but what he did know he know--a straight , middle class male's world of materialism and lust rationalized into metaphysical permanence--he understood intimately, knowingly, and was aware of how the limits makes perfect plans, perfect plans, fall apart or produce results contrary to expectations. Updike wasn't, I don't think, quite so oblivious to his renderings of women in his tales, but I think his aim, over all, was to imaginatively construct the many scenarios of how the perfect worlds of his protagonists are at odds with a universe that will not obey good or bad intentions. That he wrote about this world so beautifully--there are those times when I pick up an Updike book, say "Rabbit Run" or "The Centaur" or "The Witches of Eastwick" just to have the language figuratively roll of the page as if the words , the sentences or the fleeting notes of a transcendent Clifford Brown solo-- might be a flaw in his art, one could argue.

He makes it attractive, the prose is a seduction of a kind. Fine, that makes him dangerous for both male and women writers, which makes him artist, a great one. That makes him a pleasure to read and a pleasure worth discussing critically, as a means of understanding our own responses to his increasingly problem-making, if still alluring works,

Friday, January 27, 2012

Defending John Updike

Writer Katie Roiphe does a wonderful job defending the late novelist John Updike against the onslaught of posthumous naysaying regarding his reputation in her current piece in Slate. Cheap shots, she essentially declares, quoting the more notable snipers like David Foster Wallace and James Wood. The biggest complaint isn’t that Updike wrote badly; in fact, he is pilloried for writing too well, too often. Roiphe puts the lie to the accusations. Another charge is that the departed novelist wrote the same novel over and over, for decades, decorating rich promiscuity of his language; the sheer perfume around the prose was meant to distract us from the paucity of ideas, the lack of variety. One wonders how much Updike these critics have read. There are advantages to reading deeply and slowly.

Updike has written

novels that resemble one another in many respects over the years, but this not

issuing the same novel "over and over." I would say that he is

thematically less repetitive than Philip Roth, who is often cited as The American writer is most likely to be our next Nobel Laureate in literature. Updike

has themes and ideas that he works on in his many novels and short story

collections, but there are usually new variations, nuance, new ironies to

experience. Most good novelists you can name do this. Updike, though, was

especially keen at setting his ideas--spiritual aridity, infidelity, the denial

of death through manic activity and material acquisition, the eventual irony

as Life trudges forward unmindful of character pride or expectations--in settings

one would associate with him.

The astonishing thing about Updike is how much and how often

he experimented with form and subject, purposefully and with success straying

from the nice little container his critics try to place him in. We can also have

"Gertrude and Claudius," his lively prequel to "Hamlet,"

"Terrorist," an especially intense character study of an

American-born jingoistic, and "Brazil," a favorite of mine, an inspired

turn at Magic Realism. These novels, as well the novels “The Coup,” “Witches of Eastwick,” and “Seek My Face”, demonstrate

an impressive range for any novelists, regardless of how high their current literary stock might happen to be. An especially irksome, which is to say knee-jerk charge leveled against the novelist is that he is an egotist and an unreconstructed narcissist, someone who fashioned a high literary style to glide through a narrow range of matters that reflects a self-absorption bordering on a psychological defect. That charge essentially consists that Updike failed at a supposed grand responsibility to connect with a community of readers who expect the characters to be sufficiently sympathetic who retain the possibility for redemption.

This is patent nonsense since the principal duty of the novelist, the poet, the artist isn't to second guess their talent and attempt a version of accomplishment and truth find as someone else might imagine it, but to explore their own perceptions in some detail against and within a variety of different situations and to see precisely where their ideas, concepts, fears take them. Calling this narcissism is a convenient way of avoiding the task of understanding Updike's fictional world. I would also substitute the word egotism with confidence--the artist worth paying attention to is the one who commits themselves fully to a style that allows them to attempt many different things to the fullest degree; to the degree that Updike wrote a considerable number of novels that are not your typical mainstream inventions--he dared to experiment with his famous style--and in doing kept his persistent themes viable and capable of yielding more nuances to his tales of the frailty of the human will, he is a master. No less than Henry James, no less than Faulkner, no less than Nabokov. Updike's stock should be much, much higher then it is, and Roiphe's article makes a persuasive argument in Updike's defense. UpdikeHHe was the best American novelist while he lived, I think, and it sticks in the craw of his detractors that there are not others who demonstrated such a brilliant consistency over many decades of writing.

This is patent nonsense since the principal duty of the novelist, the poet, the artist isn't to second guess their talent and attempt a version of accomplishment and truth find as someone else might imagine it, but to explore their own perceptions in some detail against and within a variety of different situations and to see precisely where their ideas, concepts, fears take them. Calling this narcissism is a convenient way of avoiding the task of understanding Updike's fictional world. I would also substitute the word egotism with confidence--the artist worth paying attention to is the one who commits themselves fully to a style that allows them to attempt many different things to the fullest degree; to the degree that Updike wrote a considerable number of novels that are not your typical mainstream inventions--he dared to experiment with his famous style--and in doing kept his persistent themes viable and capable of yielding more nuances to his tales of the frailty of the human will, he is a master. No less than Henry James, no less than Faulkner, no less than Nabokov. Updike's stock should be much, much higher then it is, and Roiphe's article makes a persuasive argument in Updike's defense. UpdikeHHe was the best American novelist while he lived, I think, and it sticks in the craw of his detractors that there are not others who demonstrated such a brilliant consistency over many decades of writing.

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

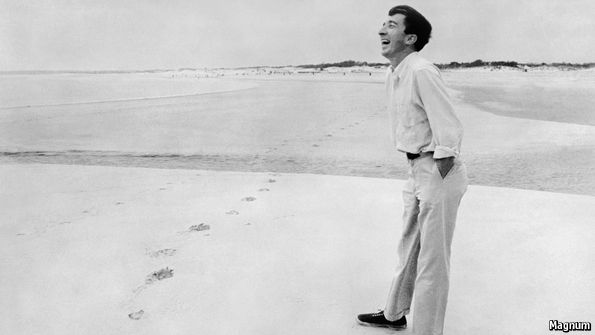

UPDIKE AT REST: Our Best Novelist is Dead:

We've lost one of our greatest novelists, John Updike, who died of lung cancer at age 76. Norman Mailer, in a breezy dismissal of Updike's novel Rabbit Run, called Updike the sort of writer who was popular with the mass of readers who knew nothing about writing. Mailer's withering glare, though, was notably fueled with obvious envy (brilliant as he was, the late writer was always obsessed with his literary competition), and what the departed Updike leaves behind is one of the most impressive bodies of work a contemporary writer, American or otherwise, would want for a legacy. His Rabbit quartet of novels--Rabbit Run, Rabbit Redux, Rabbit is Rich, Rabbit at Rest--is among the peerless accomplishments of 20th century fiction in it's chronicle of living through the confusion of the Viet Nam war, feminism, civil rights and the sexual revolution in the person of the series' titular character, Rabbit Angstrom. Not deep of thought but rich in resentment, Angstrom was an analog of American culture itself, a congested vein of self seeking that never recovered from the raw sensation of youthful vigor; Angstrom, like the country itself, resentfully fumbled about for years ruing the loss of vitality and trying to replace it with new things, the crabby possessiveness of the middle class.

Updike had been criticized, as had Nabokov, for creating characters who weren't sufficiently heroic in their suffering or sympathetic to any degree, a charge I considered a dodge against the dicier matters of personality Updike was fascinated by and lovingly detailed with his poetically charged sentences. The seduction and allure of Updike's prose was the lush and bittersweet tone he could manage while following the curious circles of sense seeking his creations walked in--within any scene, whether a room, a church, a middle-class home decorated in conflicting schools of tackiness, there would be an order things established, material goods contrasted against modified and enhanced surroundings that would offer up a vivid sense of how intoxicating, self-convincing a character's thought process can be. Updike, though, didn't trust perfect scenarios or theories as to the meaning of life and was well aware of the human quirk that seems compelled to foul the nest with self-seeking. Comic, cruel, resonating with moments that are suddenly enlarged beyond the inane doings of his sweetly deluded antagonists, Updike was the voice of the problematic white straight male libido. Everything was sex drive--love, business, politics--and that realization alone is likely what gave Updike so much material to write books about, captured in an unequaled six decades of novels, short story collections, plays, and essay collections. John Updike was that rare talent who had the capacity of vary his approach to novel writing and still remain vital, alive--the ratio of how many of his novels worked aesthetically and worked structurally within his constant experimentation with form and voice is astounding. What is amazing, as well, is how vital his novels remained as he aged--Terrorist (dealing with the obvious issue), Seek My Face (a novelization of the life of Jackson Pollack), and Gertrude and Claudius (a prelude by Updike to Shakespeare's Hamlet) among others show a fictionist of endless curiosity about things topical, historical, outside his own famous niche of New England suburbs and small towns. Tom Wolfe accused him of being among those American novelists who've missed the vitality of real people, preferring instead the easier job of writing fanciful "writer" works, but that's the sort of comment that shows that Wolfe wouldn't let the facts ruin a chance to pour gasoline on a burning resentment.

Updike, gain truth, took the pains to research a number of novel ideas and then imagine a world where the characters would live--his range of subject matter leaves one breathless. Joyce Carole Oates impresses us with her energy and her sheer productivity, but one doesn't escape the feeling that she's written the same story, with variations in tone and width, at least sixty to seventy times over in her three hundred plus volumes; Updike, a little slower yet still prolific with fifty books, left his comfort zone and applied the novelist's craft to those situations and people he felt had a story worth telling. So too comes his criticism and book reviews, which seemed to make remarks from any number of writers and subjects; his willingness to consider fiction an expandable craft made him one of the more trustworthy reviewers we've had the good luck to read over the years.

Updike had been criticized, as had Nabokov, for creating characters who weren't sufficiently heroic in their suffering or sympathetic to any degree, a charge I considered a dodge against the dicier matters of personality Updike was fascinated by and lovingly detailed with his poetically charged sentences. The seduction and allure of Updike's prose was the lush and bittersweet tone he could manage while following the curious circles of sense seeking his creations walked in--within any scene, whether a room, a church, a middle-class home decorated in conflicting schools of tackiness, there would be an order things established, material goods contrasted against modified and enhanced surroundings that would offer up a vivid sense of how intoxicating, self-convincing a character's thought process can be. Updike, though, didn't trust perfect scenarios or theories as to the meaning of life and was well aware of the human quirk that seems compelled to foul the nest with self-seeking. Comic, cruel, resonating with moments that are suddenly enlarged beyond the inane doings of his sweetly deluded antagonists, Updike was the voice of the problematic white straight male libido. Everything was sex drive--love, business, politics--and that realization alone is likely what gave Updike so much material to write books about, captured in an unequaled six decades of novels, short story collections, plays, and essay collections. John Updike was that rare talent who had the capacity of vary his approach to novel writing and still remain vital, alive--the ratio of how many of his novels worked aesthetically and worked structurally within his constant experimentation with form and voice is astounding. What is amazing, as well, is how vital his novels remained as he aged--Terrorist (dealing with the obvious issue), Seek My Face (a novelization of the life of Jackson Pollack), and Gertrude and Claudius (a prelude by Updike to Shakespeare's Hamlet) among others show a fictionist of endless curiosity about things topical, historical, outside his own famous niche of New England suburbs and small towns. Tom Wolfe accused him of being among those American novelists who've missed the vitality of real people, preferring instead the easier job of writing fanciful "writer" works, but that's the sort of comment that shows that Wolfe wouldn't let the facts ruin a chance to pour gasoline on a burning resentment.

Updike, gain truth, took the pains to research a number of novel ideas and then imagine a world where the characters would live--his range of subject matter leaves one breathless. Joyce Carole Oates impresses us with her energy and her sheer productivity, but one doesn't escape the feeling that she's written the same story, with variations in tone and width, at least sixty to seventy times over in her three hundred plus volumes; Updike, a little slower yet still prolific with fifty books, left his comfort zone and applied the novelist's craft to those situations and people he felt had a story worth telling. So too comes his criticism and book reviews, which seemed to make remarks from any number of writers and subjects; his willingness to consider fiction an expandable craft made him one of the more trustworthy reviewers we've had the good luck to read over the years.

If a writer's task is, among others, to help us understand the actions that cause us to fall down and act badly despite our best intentions, Updike has performed a patriotic service. There should be some prize for that.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

-

The firing of pop music Robert Christgau from the Village Voice by their new owners gives me yet another reason to pass up the weekly on the...

-

Why Bob Seger isn't as highly praised as Springsteen is worth asking, and it comes down to something as shallow as Springsteen being t...