The Gospel According to the Son

The Gospel According to the Sona novel by Norman Mailer

(Random House Trade Paperbacks)

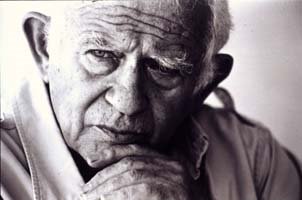

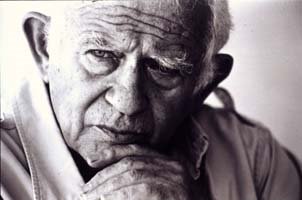

Norman Mailer has had a radical trajectory through the course of his career, and now, at age 75 with fifty years as a professional writer behind him, a summary collection is the fashion, and

The Time of Our Time is the door stopper through which posterity should judge either his ascension, or decline in our literary Olympus. It's amazing, actually, how Mailer has controlled the course of criticism of his work, as he did with

"Advertisements for Myself" and later with the Prisoner of Sex, both books through which his aesthetics were linked with a peculiarly Maileresque cosmology.There is much to argue with in The Prisoner of Sex, and though I'm in sympathy with the aims of the women's' movement, I cheer Mailers' defense of the artists right to use their sexuality and sense of the sensual world as proper fodder for poetic expression. What makes the book important is precisely the fact that Mailer felt there was a need for a man to stand up and have a word against and about the rising tide of Feminist theory; while many male writers were too confused, adrift in daydreams of irony or bottled up rage, and while the academy was surrendering its arms without a shot being fired, Mailer spoke up and wrote that there was a profound and important difference between the sexes, and that while social justice must and will prevail regarding the rights of women in the work place and overall social sphere, one cannot maintain, straight faced, that the only difference between the sexes has to do with genitalia.

There are times when Mailer- the- mystic clogs up an otherwise lacerating argument, where his romanticism veers dangerously towards a lunatics hallucinations, but his defense of Miller, Lawrence and Genet against the clumsier moments of Millet's' original critique in

"Sexual Politics" is literary criticism at its most emphatic.

"Prisoner of Sex" is, I'm afraid, incoherent at times, but there are long passages of rich knock-out prose that demonstrate why Mailer is thought by many to be one of the premiere stylists of the times, and if nothing else, his lyrical defense of D.H.Lawrence is worth the purchase by itself. One might despise Mailer and his philosophy, but a critic was still trapped discussing the work through the author's obsessions. And that is the mark of brilliance, Mailer could get is readers to talk about things he wanted to speak to, because his language is strangely persuasive, at his high point, even as it addresses the dark and obscene corners of the imagination, and the baser instincts of American power.

The Time of Our Time again makes us consider his entire career through Mailer's filter, and understandably, it can be aggravating for someone expecting an easy in to the body of work. But it gives us the rewards, with generous selections form his best work,

Naked and the Dead, Armies of the Night, Executioner's Song, An American Dream--and like wise long excerpts from slighter efforts, like "Gospel According to the Son" and his recent Picasso biography. What there is an impressive reach over the five decades that he's been in the public eye, an early brashness turning into a combative and provocative brilliance that at times trips over it's own eloquence that later turned into thoughtful, epic scale story telling through which the previous ego centric prose vanished behind the tragedy writ in the Gary Gilmore saga.

It's difficult not to be impressed with the range of Mailer's topics, in fiction, journalism, and essays! --World War 2 in the Pacific, Moon Landings, Black power, Women's Rights, Hunting, Reichian sexuality, the failure of Marxism, The Kennedy Assassination, Ancient Egypt, masculinity and American Literature, the dread of Modern architecture, the real meaning of the right wing, Boxing--and while Mailer at times seems breathless and throat clearing in his writing, that he's spreading a style too thin to cover the feeling that he's , for the moment, is bereft of anything interesting to say, you note the way he changes tact, changes styles, and ushers in another period of solid books that stand as his strongest. The Time of Our Time provides an over long reflection of a career that has been victim of the author's proclaimed desire to be the champ of his generation, but it also gives us a chance to appreciate a brilliant talent that found expression in spite of Mailer's the self-annihilating quirks. Controversial, problematic, self-absorbed, but quintessentially American, and one of the best witnesses we could have had for the second half of the century

Had Norman Mailer written

"The Gospel According to the Son" forty years ago, in the middle of a decade endlessly divided against itself, we would have a very different novel. Jesus, our narrator here, probably would have been another Maileresque hero, like Rojack in "An American Dream" or DJ in "Why Are We in Viet Nam?", a marauding, secret voice driven White Negro Hipster, committing miracles in hot, violent frenzies, a visionary on the verge of beholding the clarifying image , yet at the sacrifice of his sanity. It might have been that Mailer's obsessions and theories would have followed him into this book like a stray dog he couldn't lose and made the story as ungainly and problematic as the most congested pages of D.H. Lawrence. Unlike Lawrence, though, Mailer lived long enough to get over the brash brilliance of younger days and brace himself for a longer march. "The Gospel According to the Son", has Jesus writing his own story from a place somehow outside history, neither heaven nor hell, for the purpose of modestly correcting the gospels of his scribes Mark, Matthew, Luke and John.

The writers, this Jesus insists, have buttressed the saga in order to enlarge their fold, and declares "What is for me to tell remains neither a simple story nor without surprise, but it is true, at least to all that I recall." The same may be said for Mailer's tact in writing the story. Unlike page bombs like "Harlot's Ghost "or "Oswald's Tale", both of whose considerable merits are had after long, sluggish pages , "Gospel"is brief, a succinct 242 pages, with language that's spare and almost miserly in the use of verb and adjective.

The minimalism succeeds , as it gives the narrating Messiah a credible voice, and underscores a genius that's little discussed even by Mailer's defenders, his mastery of first person singular. As in other novels, specifically in the characters of Rojack in the heady

"An American Dream", or, closer to the new book, Marilyn Monroe in the guise of her private diary

"Of Women and their Elegance, *we have a character whose voice is divided against itself. One, there's the aspect of a young and skilled carpenter coming to knowledge that he is the Messiah and touched with duty that's beyond himself, but there's the human trait as well that and dreads, not wholly sure of the mission.

This Jesus at times occasions doubts of the reasons and effectiveness of his instructions, wonders often if God's voice might actually that of Satan's speaking too sweetly in his ear, or if he really is a madman as some call him. We are even introduced to the notion of that God Himself is not all powerful as the gospels exclaimed, but finite, as Jesus feels depleted of His power after days of performing miracles in the Temples. Credibly, there is even doubt from the weary Jesus about the wisdom of dispensing miracles at all, as the razzle - dazzle of Christ as serial healer proves a growing distraction from the teachings. Humans remain humans and concern themselves more with material comfort instead of the care of their souls, and our Jesus finds himself loathing the whole activity .This dualism is easier discussed as theological precept than it is conveyed as motivating literary action, but Mailer controls his pen with a sure hand. The spare and exacting cadences of the narrator's tone is matter-of-fact and achieves a kind of lean poetry. Both the glory of God in Heaven, and the dry, brittle facts of an earthly plain are addressed as facts of equal consequence. Because Mailer's intention is literary instead of heretical, we have a believable past that is convincingly made of hard soil upon which miracles are being dispensed.

The character of Judas is brought out splendidly in a crucial dialogue between himself and the reticent Savior. An anti -Roman agitator desiring the liberation of the Jews, Judas announces that he does not believe that Jesus can lead any people through the gates of Heaven, and that he follows Jesus solely for the political potential to galvanize a movement to toss off the Roman yoke and force them from their land. He declares he will be loyal only so long as Jesus embodies that potential . In turn, Christ responds to Judas' entreaties that he can only tend to the spiritual needs of his people, charged by his Father to bring Man back to the practice of a living faith. The opposing declarations set into motion the mechanism of an inevitable betrayal by Judas that will ironically fulfill Jesus' divine and quixotic purpose on earth.

It is written in the gospels, and repeated in Mailer's novel, that God so loved the world that He gave his only son for it's redemption. The fleeting, spectral essence of love has been a major subject of Mailer's other fiction, especially in how obsessive quests for getting and giving love become wrapped, distorted and demolished in struggles for power and influence. Mailer has investigated how these rudely combined energies result in self-made disasters through which his past heroes and heroine - -Rojack in

"American Dream", Tim Madden in

"Tough Guys Don't Dance" ,and yes, Marilyn in

"Of Women and Their Elegance" need to trust the expanded authority of their senses and earn for themselves a personal philosophy they can live with and, presumably, die for.

"The Gospel According to the Son" brings this wide current in Mailer's novels to the forefront and enlarges it vividly, and ironically, in the briefest book he's written in years. This book, finally, is about the hardest love of all, a quality of love that forces anyone to consider again if they have any capacity to be Christ -like. Mailer's superb telling of the story convinces that there's nothing heavenly in being in the slightest way divine.