I feel like a jerk and an unfeeling heel, but I cannot get beyond the feeling that Philip White's poem about his mother's frail and failing memory and health "A Moment Ago" to be just a little canned. Elision and associative leaps are hallmarks of contemporary poems, where two seemingly unlike instances or references are brought together by some synaptic spark, simulating the effect of the poet's thinking.

I feel like a jerk and an unfeeling heel, but I cannot get beyond the feeling that Philip White's poem about his mother's frail and failing memory and health "A Moment Ago" to be just a little canned. Elision and associative leaps are hallmarks of contemporary poems, where two seemingly unlike instances or references are brought together by some synaptic spark, simulating the effect of the poet's thinking.

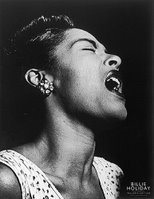

Under the best circumstances, there is the element of surprise that catches you unaware of what's coming and leaves you breathless with the end result, a point, or emotion you didn't expect to be brought to in credible condition. "The Day Lady Died" by Frank O'Hara, about the day the author heard about the death of Billie Holiday, is a splendid example of this effect, done with amazing precision and condensing of detail:

It is 12:20 in New York a Fridaythree days after Bastille day, yesit is 1959 and I go get a shoeshinebecause I will get off the 4:19 in Easthamptonat 7:15 and then go straight to dinnerand I don’t know the people who will feed meI walk up the muggy street beginning to sunand have a hamburger and a malted and buyan ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poetsin Ghana are doing these daysI go on to the bankand Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard)doesn’t even look up my balance for once in her lifeand in the GOLDEN GRIFFIN I get a little Verlainefor Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I dothink of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore orBrendan Behan’s new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègresof Genet, but I don’t, I stick with Verlaineafter practically going to sleep with quandarinessand for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANELiquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega andthen I go back where I came from to 6th Avenueand the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatre andcasually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a cartonof Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face on itand I am sweating a lot by now and thinking ofleaning on the john door in the 5 SPOTwhile she whispered a song along the keyboardto Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

-- Frank O'Hara

It's a poem about going about one's business in a city legend for hustle and frenetic activities, comings and goings, and O'Hara's casual survey of the limitless details of what the city reveals (there is a feeling in this poem of painter Stuart Davis' pre-Pop Art cityscapes, large, blocky, jazzy and absolutely electric), the issue of Holliday's death is unmentioned save for a passing headline. O'Hara goes about his errands, his distractions until he remembers a seat in a comfortable jazz bar, and the tragedy, the sorrow, the irreplaceable loss hits him finally and suddenly and the room was impossible still as she started to sing. O'Hara gets the sense of revealed truth, the rush of sensation that rings every bell and tells you that life is different now and a bit diminished, that whatever you've learned from the departed will either be your strength or your weakness.White reads like he's only more than eager to convert his sadness into a poem. O'Hara's verse was a conversation and offers up his revelation as if it were a bit a self-knowledge that emerges in a talk quick and unexpectedly, White' sentences are stiff in their writerly vestments:

We were out on the deck talking with mother,watching the line of shadow climb the foothills,intercepting the peaks around us one by oneas if the valley were a bowl being slowly filledwith darkness. She wore the blue cloth hatwith a flower, having just given up therapy.We asked what she remembered of "little"great-grandma and others we never knew.It was hot. An afternoon storm had splotchedhere and there the laurels, startling the swallows;a dusty trickle had formed briefly in the throatsof the gutters

This is prose, first off, and it suffers from obvious conceits such as the strained conceit of equating the time of day with the state of his mother's health and memory; sad as it is, in fact, does not make moving as a piece of writing by default. The fading light, the darkness engulfing the mountains, it's a cement shod set up for the delivery of the punchlines, the mother's interruption of her recollection with a frail mention of a song she suddenly remembered, something she brings up unexpectedly. What happens with the material is the kind of gutless literary writing that is over polished, seeming graceful and poetic at first, but which comes across as inconclusive in how an emotion is received. It's an aesthetic distance that decorates the bare facts of compounding sadness whose rhetorical style, a conspicuous overkill of fine writing, avoids a response that reveals something cracked in one's perceptual armor. The mother is made into an exercise in slipshod allusion and creaky, unsurprising metaphors.I don't expect poems to make sense literally, or to be snapshot perfect in how they recreate the factual world since what interests me generally is how the writer creates a credible mood. What's interesting half the time is the skewed details. My objection is White's fervor to smother everything with thick, glorious language that is arranged just to show his mastery of the tongue rather than let on what it is he feels. Not that I'm crazy about poets who pump and gush feelings like leaky hoses, but one does note the lack of felt experience here.

White's literary reputation is more the issue of the poem, not the state and being of his supposedly dear mother. She exists here solely to provide the poetic moment for the poet to deliver his prepackaged cadences and storeroom ironies. .White might have been saying "Oh wow" to himself while all this was going on, and was mentally framing the poem as he stood there, maintaining a concerned face. If a sister or a brother slapped that concerned face after reading this poem, I wouldn't be surprised.