Thursday, May 21, 2015

So Long David Letterman

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

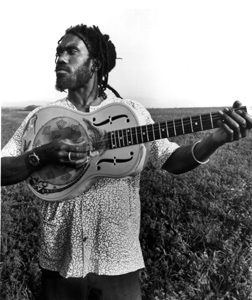

Can White People Sing the Blues?

Corey Harris, a fine blues guitarist, songwriter, and singer in a neo-traditionalist blues style, writes a provocative column on his blog Blues is Black Music entitled "Can White People Sing the Blues?" Harris, a musician, specializing in a style of blues that's been around much longer than his years on this earth, insists it's an important question. His primary objection of whites playing what is a black art form is this: that while listeners are entertained by technical competence and show business bedazzlement, they do not have legitimacy because the music is robbed of historical context and is, as a result, merely ornamentation, not art that convincingly interprets personal and collective experience in a cruel, problematic existence. There is no culture without the long, collective memory to inform it and keep it honest.

" Without culture there is no music. Music is the voice of a culture. Separate the two and the music can never be the same. Of course, it may be in the same style as the original, but the meaning of a song such as Son House's 'My Black Mama' will always be changed with a different performer. This is especially true if the performer is not from the Black culture that gave birth to the blues."

I agree that those aspiring to perform blues, jazz, or soul

should forever know what they are picking up is black music created by and

defined by black artists and the culture, twisted as it may have been,

that contained the forces that brought together elements of African and

European tradition that otherwise would not have met. Would that the

institutions that created the genius of African American music hadn't been the

racist and economically determinist demon of Slavery? Harris, though, assumes

that culture is static and implies that black culture has remained still. The

creation of Black American culture regarding art, education,

literature, music, theatre, speech, theology refutes that rather handily, as it

arises, through forced circumstances, from a system of oppression; oppressed

classes create counter-institutions.

The new black culture gradually arose and developed as the response by black

communities to the decimation of the institutional, social and spiritual

traditions that had been theirs in their own land. The new culture, in turn, influenced

the larger culture, the culture of white people. One can single out exploitation,

minstrelsy, racist practices, blatantly bad, and watered-down imitations of

popular and emerging black art forms, especially musical idioms. Still, there

is the area of the personal, localized, and influence of blues culture on white

musicians apart from record companies, promoters, and agents where the younger

musician is influenced and, in effect, being mentored by the Black

musicians they admired took their cues from. Harris makes a powerful

argument based on a series of cherry-picked conceits to the exclusion

of glaring contradictions. He speaks that the metaphysical essence of blues is

feeling, emotion, the ability of the human voice to convey true experience, and

yet he speaks in racial absolutes, denying the capacity of individual musicians,

black and white, to transcend, mature, grow out of the imitative phase and

achieve a true feeling, a true vision of the music they love. The case is that while self-righteous revisionist scolds like

Harris is articulate will limit the range of blues to exclude all who are not

black from having true blues authenticity, art does not sustain itself by

remaining in a vacuum. No matter how righteous the music's argument belongs to,

without the constant input from musicians attracted to it and performing it according

to the narrative of their personal lives, the music ceases to grow. It shrivels

up and dies and becomes only a relic, notable mostly for its distant and

antiquated sound.

We will admit without reservation, upfront and unconditionally, that blues and jazz are Black-American creations. It's important to keep that fact in mind. Still, the blues, being music, is something that catches the ear of the blues lover, regardless of race, and speaks to those people in profound ways, giving expression to perceptions, emotions, personal contradictions in ways that mere intellectual endeavor cannot; it is this music these folks come to love, and many aspire to play, to make their own and stamp with their own personality and twists and quirks. That is how art, any art, survives, grows, remains relevant enough for the born-again righteousness of Harris to reshuffle a less interesting set of arguments from LeRoi Jones' book "Blues People."

There is the aspect that blues is something in which anyone one

can play the game, an element that exists in any instance of art one thinks

ought to be restricted to particular groups, but what really matters

is less how many musicians have gotten in on the game as much as how many are

still on the playing field over the years, with great tunes, memorable

performances, slick licks, and most importantly, emotions that are

real, emphatic, unmistakable. There is no music without real emotion and new

inspiration from younger players bringing their own version of the wide and

dispersed American narrative to the idiom. There is no art, and it dies, falls

into irrelevancy, and is forgotten altogether.

Friday, May 8, 2015

Avengers: Age of Ulcers

We can agree that director and writer Joss Whedon had done a brilliant job of coordinating the cinematic Marvel Universe efforts, both amazing--Iron Man, Captain America:The First Avenger--and lackluster (Thor) so that that they all lead up to the gloriously noisy, jokey, jivey, dynamic and breathtakingly awesome Marvel's Avengers movie. This was a magnificent first movement in a plan that is said to be composed of three different phases of how Marvel comics plans to bring their comic book characters to the big screen and much smaller streaming device. Action, insults, just enough dramatic interaction between nominal heroes, hammy performances by central villians and, true to the Marvel comic book heritage, a devastation of a good part of New York City while good guys and invading aliens battle one another. Now what?

We can agree that director and writer Joss Whedon had done a brilliant job of coordinating the cinematic Marvel Universe efforts, both amazing--Iron Man, Captain America:The First Avenger--and lackluster (Thor) so that that they all lead up to the gloriously noisy, jokey, jivey, dynamic and breathtakingly awesome Marvel's Avengers movie. This was a magnificent first movement in a plan that is said to be composed of three different phases of how Marvel comics plans to bring their comic book characters to the big screen and much smaller streaming device. Action, insults, just enough dramatic interaction between nominal heroes, hammy performances by central villians and, true to the Marvel comic book heritage, a devastation of a good part of New York City while good guys and invading aliens battle one another. Now what?Wednesday, May 6, 2015

Whitman or Pound?

Finally, I would ask who is more readable and provides more pleasure?Pound was sane, of course, but he was more a literary critic than poet. As for poetry , I would cite Eliot as the superior influence as to how poets of succeeding generations formed their sense of what actual verse should sound like and achieve. Eliot was a better artist, Pound the better cheer leader for the movement.

Thursday, April 16, 2015

notes on Jack Spicer

The poet loses control of what his poet is supposed to mean as history adds associations to the syntactical skin. Spicer, I suspect, might well object to the use, but there is a savage bluntness about poets and their varied attempts to find a greater resonance from the obscenity of violence that resonates with what we're remembering today. What Spicer intended is a moot point, and in this instance, inconsequential. Today was the day everything changed, as they overused phrase went, and that meant everyone had to take a hard look at who they were, who they said they were, and why that mattered in the face of such insane destruction. Spicer, not the least, likely would have considered long and hard; there is the notion that what you've said in a situation you want to clarify gets repeated against seemingly opposing backgrounds. The voices from out of the air, from the radio of memory, are triggered by extraordinary events that transform our regular which, after all, are not static in any sense. Silliman's collage is an inspired combination of histories; they are no longer mutually exclusive.

Interrogation of received notions was his ongoing the theme, and ‘through the practice of making literary practice the unifying metaphor in a body of work tends to seal off poetry from a readership that could benefit from a skewed viewpoint—unlocking a door only to find another locked door, or a brick wall ceases to be amusing once one begins to read poets for things other than status—Spicer rather positions the whole profession and the art as an item among a range of other activities individuals take on to make their daily life cohere with a faint purpose, they might feel welling inside them. Spicer, in matters of money, sexuality, poetry, religion zeros on the neatly paired arrangements our language system indexes our hairiest ideas with and sniffs a rat when the description opts for the easily deployed adjectives, similes, and conclusions that make the hours go faster.

Thing Language

By Jack Spicer

This ocean, humiliating in its disguises

Tougher than anything.

No one listens to poetry. The ocean

Does not mean to be listened to. A drop

Or crash of water. It means

Nothing.

It

Is bread and butter

Pepper and salt. The death

That young men hope for. Aimlessly

It pounds the shore. White and aimless signals. No

One listens to poetry.

There is a reservedly antagonistic undercurrent to Spicer’s work, the subtle and ironic derision of the language arts that, as he sees them practiced, is locked up in matters of petty matters of status, property, the ownership of ideas, the expansion of respective egos that mistake their basic cleverness for genius. The world, the external and physical realm that one cannot know but only describe with terms that continually need to be resuscitated, is, as we know, something else altogether that hasn’t the need for elaborate vocabularies that compare Nature and Reality with everything a poet can get his or her hands on. What this proves, Spicer thinks (it seems to me, in any event) is that we know nothing of the material we try to distill in verse; even our language is parted out from other dialogues.

The Sporting Life

By Jack Spicer

The trouble with comparing a poet with a radio is that radios

don't develop scar-tissue. The tubes burn out, or with a

transistor, which most souls are, the battery or diagram

burns out replacable or not replacable, but not like that

punchdrunk fighter in a bar. The poet

Takes too many messages. The right to the ear that floored him

in New Jersey. The right to say that he stood six rounds with

a champion.

Then they sell beer or go on sporting commissions, or, if the

scar tissue is too heavy, demonstrate in a bar where the

invisible champions might not have hit him. Too many of

them.

The poet is a radio. The poet is a liar. The poet is a

counterpunching radio.

And those messages (God would not damn them) do not even

know they are champions.

Spicer is an interesting poet on several levels, all of the deep and rich with deposits that reward an earnest dig. He is, I think, on a par with Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams with the interest in grilling the elaborative infrastructure of how we draw or are drawn to specialized conclusions with the use of metaphor, and it is to his particular brilliance as a lyric poet, comparable to Frank O’Hara (a poet Spicer declared he didn’t care for, with O’Hara thinking much the same in kind) that the contradictions, competing desires and unexpected conundrums of investigating one’s verbal stream are made comprehensible to the senses, a joy to the ear. No one, really no one wrote as distinctly as the long obscure Spicer did, and editors Gizzi, Killian and publisher Wesleyan Press are to be thanked for restoring a major American voice to our shared canon.

Book Of Music

by Jack Spicer

Coming at an end, the lovers

Are exhausted like two swimmers. Where

Did it end? There is no telling. No love is

Like an ocean with the dizzy procession of the waves' boundaries

From which two can emerge exhausted, nor long goodbye

Like death.

Coming at an end. Rather, I would say, like a length

Of coiled rope

Which does not disguise in the final twists of its lengths

Its endings.

But, you will say, we loved

And some parts of us loved

And the rest of us will remain

Two persons. Yes,

Poetry ends like a rope.

A cynic's view, perhaps, where the picture that's painted first has the gasping awe of young love, perfect, endless like a circle, the world itself, and later, destroyed, cut at the vital moment of greatest vulnerability, merely a thick string that starts at one end and merely ends, absent glory or beauty, at another. Even after the twists and turns of the thing itself--love, the foiled circle--to restore itself in reactionary spasms, things just end, and rapture and passion are replaced by bitter memory, a bitterness that gives way to a mellowed skepticism, if one is lucky to live long enough to be a witness their foolish expectations of people, places, things, and especially the foolishness one might have said about poetry in whatever earnest declarations one uttered in classrooms, dorm rooms, cafes where the intelligent and underpaid gathered for a cheap drink and company.

What is artistry?

Artistry begins when you forget your own ideas about what art is and what art making is and find yourself fully engaged in a moment of absolute creation, when everything you know how to do intellectually, technically and can access at command just come to you as easily as taking a breath; it happens seamlessly. It's more than remember the advice that you cannot let the audience see you sweat and become aware of rattled nerves and possible indecision, it is forgetting that you are nervous and full of self-doubt at all and taking the fabled Kierkegaardian Leap Of Faith, that jump over the abyss of self-sabotage and knowing that whatever the consequences are better than another minute of wallowing in the rut we've had furnished and moved into. Artistry, to trade further in cliches, is that existential moment where one discovers not the meaning of life over all but rather meaning to their life specifically by an ethically bound commitment to creativity.

Artistry begins when you forget your own ideas about what art is and what art making is and find yourself fully engaged in a moment of absolute creation, when everything you know how to do intellectually, technically and can access at command just come to you as easily as taking a breath; it happens seamlessly. It's more than remember the advice that you cannot let the audience see you sweat and become aware of rattled nerves and possible indecision, it is forgetting that you are nervous and full of self-doubt at all and taking the fabled Kierkegaardian Leap Of Faith, that jump over the abyss of self-sabotage and knowing that whatever the consequences are better than another minute of wallowing in the rut we've had furnished and moved into. Artistry, to trade further in cliches, is that existential moment where one discovers not the meaning of life over all but rather meaning to their life specifically by an ethically bound commitment to creativity.Wednesday, April 15, 2015

Genius arising from limitation

Monday, April 13, 2015

The heart loves what the heart loves

Friday, April 3, 2015

About Steve Kowit

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

With Great Power Comes Liabilities

The difference is that a super power is an ability that the hero can control and use at will when the need arises; what's been shown so far for the power is that it is incredibly destructive when it is used (or goes off, rather) potentially laying waste to lives and property, and that it leaves Superman bereft of powers, vulnerable . We cannot assume that the super flare would always vanquish his foes. So the question becomes as to what practical use this trait is and whether it is something that Big Blue can learn to control and employ appropriately with less catastrophic results. I suspect that we've just opened the door for yet another Superman weakness, as if limitless amounts of kryptonite and undifferentiated brands of magic weren't enough. Superman too powerful? Set off the flare and lets see how he fends as a mortal. This can become a go-to device too easily. I'm interested to see what they do with the super flare, but it wouldn't be surprising that they've shot their wad.

Monday, February 23, 2015

Slate arts wonk has a fit over "Boyhood" not getting Oscar Best Picture

'via Blog this'

This film is a about as meta-textual as it gets, concerning a actor named Riggan who, best known for portraying the cartoon super hero Birdman in three live action films, is attempting a comeback on broadway with a stage adaptation of a collection of Raymond Carver short stories, 'What We Talk About When We Talk About Love".

The first inside joke, of course, is that star Michael Keaton was the first Batman in two Tim Burton versions of the DC icon, who had the oft circulated take away line "I'm Batman" when the Dark Knight introduces himself to the Gotham crime element. Keaton's character in this new film has a mind that is subdivided with conflict, a string of unresolved issues that force him to hallucinate greatly, not the least of which is a voice that rasps only to him "YOU'RE BIRDMAN", and which harshly chastises him for abandoning the super hero for the delusion that he could become part of the New York arts crowd.

That's all a bunch of shit, the voice insists, and intrudes on the actor's private moments with more berating and demands that he give up this Broadway charade and reclaim his one true calling , the man who is the definitive Birdman. The film, though, is quite a bit more than that, as it brings around a provocative stream of old associations, like an estranged daughter, an estranged daughter he's only recently reconciled with (if imperfectly), acting rivals , all of whom , between hallucinations, have wonderfully nuanced confrontations with Riggan and with each other on the irony latent in the countless attempts we make to rid ourselves of masks and present our true selves to things that matter most , such as marriage, rearing children, authentically gratifying work, only to realize that even the true self presented as evidence of no disguise is itself a mask, a disguise.

The conflicted Riggan is jerked about emotionally and has several instances where the hallucinations, the warring desires, take over and the film is transformed into yet another space, a surreal terrain of tall buildings, floating, spectacles that then dissipate as the conflicted hero emerges from his melodrama and attempts to finish what he's begun, the afore said adaptation for the screen. A fine cast of characters abound here, and a superlative roster of actors to bring their quirks and vulnerabilities to the screen; Edward Norton, Emma Stone, Naomi Watts are sublime and each of them have solidly written, deftly directed roles.

-

Why Bob Seger isn't as highly praised as Springsteen is worth asking, and it comes down to something as shallow as Springsteen being t...

-

here