Quentin Tarantino likes to dress up his films in the mannerisms of directors he admires, a cut and paste style that has resulted in occasional brilliance and one real masterpiece, Pulp Fiction. The energy and playfulness, however, has become wearisome as this fellow repeats and reiterates his moves, stylistically and intellectually. "Death Proof", his contribution to the "Grind House" collaboration with Richard Rodriguez, was something of a "Pulp Fiction" knock off, overly stylized dialogues about not much in particular slowing down the narrative momentum like a big thumb on an old turntable, and "Inglorious Basterds" was this film maker at his most hollowed-out, glib, verbose, lazily constructed, scenes drawn out and shocks and surprises twists slipped in along the way as a means to distract us from the fact that Tarantino's bag of tricks was a small one to begin with.

Tarantino fatigue has set in; what made him hip now makes him seem like a gimmick prone stylist living up to fan expectations; I think of good amount of Fellini when the subject of Quentin arises. Is destined to make a million motion pictures the contents are familiar to the point of contempt? There is a strong chance, unless Hollywood runs out of money first. Even Pulp Fiction, his best effort, seems dog eared just as Citizen Kane seems over stuffed. PF will hang around Tarantino's neck for as long as he lives because it will be regarded, always, as the best thing he's ever done. It remains a powerful film for the most part, full of wicked laughs and and re-convolutions of seamy paperback action novels, but it does show it's age.

The dialogue is something else altogether, but does anyone really think he's done better than the Master, Elmore Leonard? The dialogue, as such, are extended riffs divorced from the violence and action, a sort of virtuosity that is more obtrusive than revealing; the beauty of pulp fiction was that its minimalist discussions, compact, jargon filled, quirky and redolent in references that suggested a sub culture beyond the melodrama of the basic plot, were models of virtuoso concision. The dialogue here merely stalls, stops, occupies time like it were a waiting room. Seeing these characters again go on about the differences in burger joints between Amsterdam and America, the finer points of foot massage and revenge, on changing one's way of life due to a revealed miracle, makes you wish something would happen that was gratuitous and without justification. Anything to get on with it.

The irony about the matter of Tarantino is that while he maintains the loves, admires and discusses eloquently the elegant leanness and clean procedural logic of genre films, he cannot make films near their perfection because of his verbosity; as Duncan Shepherd wrote, he "...likes to hear himself write". It's not that action genre films cannot have compelling or intellectually compelling dialogue; the problem lies in Tarantino's deficiencies as a screen writer. What he thinks are layers of ironic misdirection,where absolute monsters or amoral reprobates are given reams of well -honed speeches to recite between spasms of bad-doings are, in fact, padding and time wasting.

Even Elmore Leonard, the king of dialogue, knows to tailor his exchanges to advancing the action and the surprises. Leonard has sage advice to those younger writers who desire to have readers finish the books they write or the movies they author:"

Quentin Tarantino makes me think increasingly of the bright musician of generous technique and dexterity who forsakes sheet music, or even head arrangements and insists instead of improvising, from a cold start. Keith Jarrett comes to mind, superb pianist in group contexts who, somewhere in the Seventies, elevated himself to a concert soloist, literally, with a series of multi-disc live releases highlighting his ability to extemporize melody and development. Tension and release is the key to keeping any soloing alive, an element that requires pacing; the problem with Jarrett's elongated improvisations , it seemed to me, that he too often went frameworks that supported his configurations and offered up, at extended rates, a form of noodling, riffing, a repetitive set of rills and streaming, gutless variations that lacked adventure, daring. Jarrett, unknown to him and ignored by his fans, had turned into a New Age pianist, a verbose George Winston. I couldn't wait for the man to ease himself back into band situations, which he has, and good for him,and good for us. Inglorious Basterds , writer-director's Tarantino's homage and ramping up of the Men- On -a-Suicide- Mission war drama , is a flashy, occasionally gripping bit of now dated mannerisms characteristic of the film maker who loves to hear his voice emerge from the mouths of characters he creates. The characters are sock puppets, and what used to be style work has become shtick through repetition. The plot points Tarantino writes over are not notes to a melody he would lovingly embellish , but are considered as little more than a chord progression over which he has another excuse to blitzkrieg us with dazzling technique, a habit that becomes deadening before too long.

Shtick, though, can still be fun if deployed in a lively way, and there are moments when the predilection of long monologues or convoluted stretches of dialogue that lead , at snail pace, to an expected burst of violence grabs you by scruff and bangs you around some, the obvious example being the performance of Christoph Waltz as the charming, effete, well mannered and murderous S.S. officer Col. Lada. Waltz is inspired as he embodies the self aware elegance of a man who likes nothing better than to exterminate Jews for the Nazi command. He cannot, though , balance Waltz's performance with an effective counterweight; Brad Pitt, of late the most interestng Hollywood actor with the roles he's taken --Burn After Reading, The Assassination of Jessie James by The Coward Robert Ford, Killing Them Softly-- but in Basterds he's only on screen less than half the screen time, and he is impaired beyond belief by a cartoonish Tennessee* accent. Pitt has the appealing skill of vanishing inside the character's skin and letting his physicality become inhabited by another personality , full of ticks and twitches. Unlike Al Pacino, say, who battles to conquer a writer's character with his trademark rages and rasping , ranting style, Pitt's portrayals strike you as people you wouldn't look at twice; this is the talent to seem insignificant until a series of gestures and reactions reveals an unannounced agenda. Except here, significantly; Pitt looks like he's practicing his accent in a mirror while he studies the smooth curves of his face. It never becomes a comfortable fit.

The Lada speeches go on for extended lengths,reprising feints, indirections and nuanced deceits of past Tarantino movies. Tarantino hadn't an outline for this film, a structure to hang his best ideas on; rather , he improvised from the outset, the result that his worst tendencies show up as often as his best virtues. Which made Inglorious Basterds an unpaced endurance contest.

He reached his saturation point with steroidizing movie genres with his two part masterpiece Kill Bill, with all it's seamless and bravura conflations of different action film styles, but he has based his reputation on this one knack, or , more accurately, this habit. Death Proof was a chatty, grinding bore, with the fabled Tarantino dialogue sounding like left over material that didn't make into the frothy exuberence in Pulp Fiction or True Lies (the late Tony Scott directing Taratino's original screenplay). Inglorious Basterds continues the downward spiral despite the generous reviews from critics eager to crown him an auteur, continues the downward spiral.

His sleights of hand, his post modern conflations, his promiscuous homages to film styles that drag down his narrative momentum--hard rock guitar riffing in a WW2 movie? Whoa, cutting edge stuff-- fail to lift this bit of labored pandemonium . Eccentric liberties with formula plot structures made items like Pulp Fiction and the pair of Kill Bill movies fun things to sit through, a superb blend of film making panache and a young man's energy to jack up the action; even his incessant references to other movies were endearing because you sensed the director had shoved two generations of film theory to the side and resolved that movies were fun; aesthetics were a matter of making the entertainment more intense.

What hasn't happened the maturation of the approach; fun can still be of value in itself, but there is the expectation that an artist has developed a finer sense of what that entails; themes ought to transform over time. The aging wunderkind remains on the same playground, though. As with Death Proof, Inglorious Basterds isn't an improvement on an original idea, but rather someone of limited ideas determined to tell the same jokes over and over. It would be one thing if he were developing his themes, but Tarantino loves his riffs and mulled-over mannerisms too much to alter them, to play with them. He loves them way a thief loves his stolen booty. No matter how lovingly he polishes and resets these things, you are aware that they don't belong to him.

___________

On the subject of" Pulp Fiction", I will say again that I think that film is a masterpiece, sheer inspiration in ways of writing, editing, acting. Everything that Tarantino does in the film is fresh and alive, a lively recasting of venerable Hollywood genre. The essential problem is that he uses the same tact over and over; directors are allowed to repeat certain things they do, since that is the essence of having a style. But the point of having an identifiable style is being able to do different and unexpected things within the recognizable framework. Howard Hawks, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock and other auteurs too numerous to mention made movies praised for being individually stylish and avoiding the charge, for the most part, of being lesser variations of past successes. What Tarantino has done is repeat himself, in a succession of films, that threaten to downgrade his method from "style" to mere shtick. I would argue that virtually all of Tarantino's movies are reboots, in his case , the rebooting of a genre, be they crime stories, samurai tales, a war film, a western. Doubtless he'll resurrect the Hollywood musical, do a spy film and present us with super hero movie. Those genre revivals, though, needn't be the over packed, eager to please student projects his last three films have been. As he did with his wonderful adaptation of Elmore Leonard's crime novel "Rum Punch" in the form of "Jackie Brown", Tarantino has the ability to let the tale advance without the worrying , hovering , obvious obsession to make the scene more clever than it needs to be. Many were disappointed when "JB" came out because it wasn't another "Reservoir Dogs" or "Pulp Fiction"; I liked the way he scaled back his style, letting Leonard's plot unwind, allow the characters to have breathing room in the film space they inhabited, letting the conversation ring stylish, idiomatic and true. What would be interesting is if Tarantino became bored with his established approach and challenged himself. " __

Who are these scribes and pens, coughing up balls of dust

each time a floor board creaks underfoot or a cat on the porch meows and

scratches doors, looking for a family to move in with? Handwriting is a trail

of tears and terror under the singing springs, there are bills to pay, stamps

to lick, a metaphor to ponder as fingers stroke pens to remember an address

while cramped under a mattress .What shall we write about, oh yes, half a bird

on the sill, a lone cup on the far table, ankles defacing the knot holes with

unforgiving heels, but now, is the coast clear, is there anyone watching?

Who are these scribes and pens, coughing up balls of dust

each time a floor board creaks underfoot or a cat on the porch meows and

scratches doors, looking for a family to move in with? Handwriting is a trail

of tears and terror under the singing springs, there are bills to pay, stamps

to lick, a metaphor to ponder as fingers stroke pens to remember an address

while cramped under a mattress .What shall we write about, oh yes, half a bird

on the sill, a lone cup on the far table, ankles defacing the knot holes with

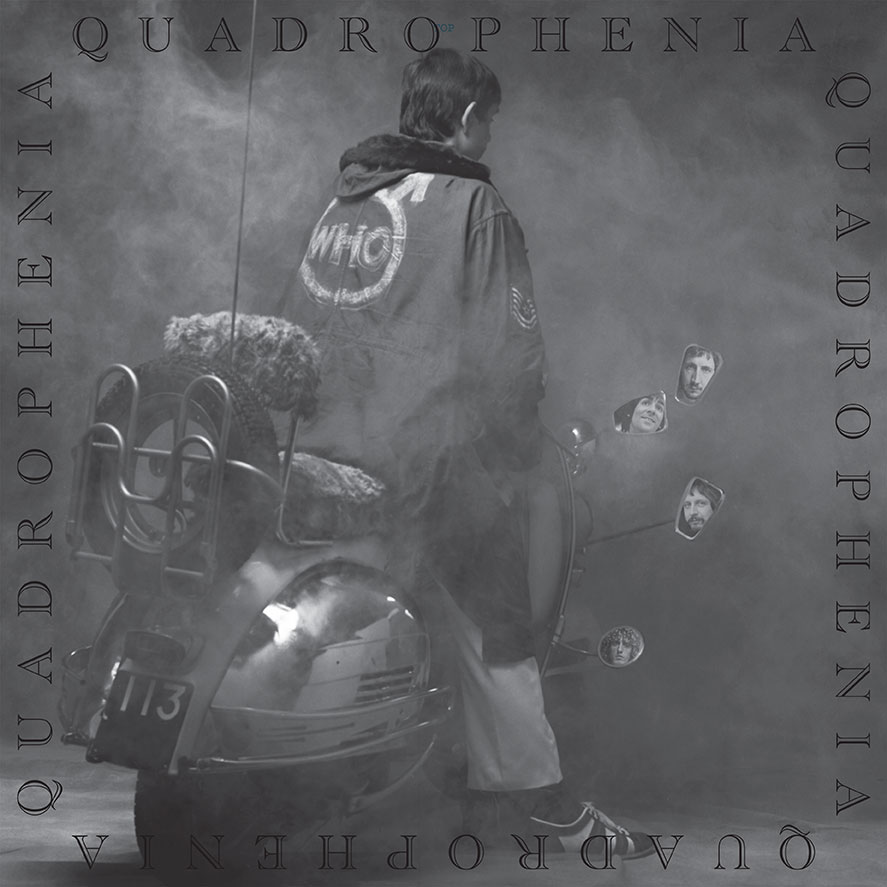

unforgiving heels, but now, is the coast clear, is there anyone watching?  The Who's Quadrophenia is one of the dullest albums ever released by a major rock band; it marks the spot where songwriter and guitarist Peter Townsend's abandoned (or lost) his genius for composing witty rock and roll and wicked power chords that were the cornerstone of all things anthemic in the grinding morass that largely was rock and roll when bands sought no longer to be fun or entertaining, but significant. There is nothing wrong with significance on the face of it, but that quality is generally the result of inspired work and an unmediated commitment to a creative surge that cannot, truthfully, be duplicated by force of will. Townsend, in my view, opted to make significant states in his lyrics at the sacrifice of the light touch he could frame in the context of a four chord song.

The Who's Quadrophenia is one of the dullest albums ever released by a major rock band; it marks the spot where songwriter and guitarist Peter Townsend's abandoned (or lost) his genius for composing witty rock and roll and wicked power chords that were the cornerstone of all things anthemic in the grinding morass that largely was rock and roll when bands sought no longer to be fun or entertaining, but significant. There is nothing wrong with significance on the face of it, but that quality is generally the result of inspired work and an unmediated commitment to a creative surge that cannot, truthfully, be duplicated by force of will. Townsend, in my view, opted to make significant states in his lyrics at the sacrifice of the light touch he could frame in the context of a four chord song.