Infinite Jest is perhaps the most exasperating novel I've ever read, along with being the most chronically overrated in contemporary fiction. It may be argued that he novel is about the digressions he favors, and that such digressions place him in line as being the latest "systems novelist", taking up where Gaddis, Pynchon, DeLillo and Barth (John) have led the way, to which I'd say fine, and what of it? The AA and recovery material is potential good fun, and the aspect of powerlessness over a movie ought to be enough for a writer to mold a sure satire, but Wallace seems far too eager to surpass "Gravity's Rainbow" and

"The Recognitions" in his long, rhythm less sentences. The aforementioned editor I proposed would have handed the manuscript back with the observation that this set of multi-channeled satires has already been done by the previously mentioned authors whose works are not likely to be matched. Said editor would then advise that over-writing isn't the sure means to break with your influences, but that developing one's own style is.

There is a well argued rationale for the lack of editing in Infinite Jest, that David Foster Wallace was in the tradition of testing the limits of a what a sentence, a paragraph, a page can contain before the onset of the concluding period, the test being that a sentence can drift, digress, take long turns and circuitous routes to the finish a series of ideas,but even digressions have to be pared down to the ones that will have an effect, even a diffuse one that. Wallace really isn't in control of his digressions. Every so-called postmodern writer has to decide , and finally know what effect and point, or drift, they are getting at.

Even in an style whose hall marks are pastiche, parody and high-minded satire, craft still counts for something, and a sense of the form a book is taking, it's architecture, has to come under control, or else the eventual point of the writing, to study, in an imaginative terrain, some aspects of the human experience, lost entirely. Any working novelist, whether a genre-hack , a royalist, avant-gardes of most any hue, ought to be in control of their materials, where Wallace, with IJ, clearly isn't.

That control is more instinctual than mechanical, and the ability to know when to stop and allow the fictional incidents resonate in all their overlapping parts. Wallace doesn't trust his instincts, or his readers powers to interpret his material, I guess. There is always one more paragraph, one more digression, one more bit of undigested research for him to add. It's like watching a guy empty his pockets into a plastic tray at an airport metal detector. White Noise is written, of course, in a spare and professorial style that some might find maybe too much so. I didn't have that problem, and thought the style perfect for the comedy he wrote. It's a college satire, and was a remarkable choice on his part to convey the distorted elements of the story line, from the lush descriptions of the sun sets , et al. It's a prose style that is brilliant and alive to idea and incident: DeLillo has the rare genius to combine the abstract elements of a philosophical debate with imagery - rich writing that manages several narrative movements at once. His digressions meet and merge with his descriptions, and the result is a true and brooding fiction that aligns the comic with the horrific in a series of novels where the pure chase for meaning within systems of absolute certainty are chipped away at, eroded with many layers of a dead metaphor , slamming up against an unknowable reality that these systems , including literature itself, have claimed entree into. Heady, compulsively readable, vibrantly poetic.Mao ll, Underworld are among the best American novels written in the 20th century.

Sunday, January 14, 2018

The Tattooed Girl by Joyce Carol Oates

Joyce Carol Oates is not my favorite writer, but for all the repetition of her themes of fragile women being imperiled by evil masculine forces they masochistically desire, she does occasionally publish something both compelling and well written. I detested Beasts and The Falls since she exercises her familiar dreads in contrasting lengths, the first book a slender novella, the latter a literal brick, both books sounding rushed, fevered, and breathless, as first drafts of novels usually do. Or a finished Oates novel, for that matter. She does hammer that nail effectively and brutally as often as not, however, as she did with her novels Black Water and The Tattoo Girl", with the right configuration, her usual wit's end prose style and fascination with fragile psyches and marginally psychotic psychologies get as intense as fiction is ever likely to get. Zombie is a rather potent little psychodrama, and it's the kind of writing Oates excels at. She gets to the heart of the fringe personality better than anyone I can think of. The Tattooed Girl, from 2003, is likewise a well shaped melodrama. She depicts the thinking of women who allow themselves to be beaten and killed with seemingly scary exactitude. Oates can also be a bore, evident in We Were Mulvaneys and The Falls. My fascination with her continues, though, since it's impossible to tell when she publishes another novel that will be gripping and unnerving. I agree with the assessment on Oates. She writes so much that she's almost as undercooked and sometimes awful as she is brilliant. Producing novels at such an assembly line clip seems a compulsion. We Were Mulvaneys read like it was meant to capture some of the weepy women's market and I put it down, and Beasts was a novella of abuse that was better left in the manila envelope, as it was a flat litany of sexual assaults that she's done better before. But just as you think Oates is all used up, she surprises you. The Tattooed Girl was an amazing book, as was The Falls, with their portents of violence, domination, skewed rationalization of unworthy deeds. She has made an art of the dystopian personality, and it is here that she gets greatness. She merits a bit of respect, although you wish she'd stop trying to win the Nobel Prize so obviously with her tool-and-dye production and take longer to write a novel a reader didn't have to rationalize about. Editors hold much less sway in the preparation of a book, it seems. It's not just a matter of writers who write quickly getting away with redundant excess and awkward passages, such as Oates and Stephen King. Those who take their time also seem to avoid the more severe markings of the editor's blue pencil .

Wednesday, January 10, 2018

The Huffington Post Rips Down an Article Sharply Criticizing Spotify — Here's the Original

The Huffington Post Rips Down an Article Sharply Criticizing Spotify — Here's the Original:

This is worth reading because it makes the case convincingly that musician creators are getting the short end of the stick financially from having their music featured on the Spotify streaming service. The caveat is that I find the author's recollection of the conversation with a Spotify executive about the financial relationship between the service and the creators who make their content reads a little pat. The executive comes across as too stereotypically dense and clueless and the narrator shows himself as a guy who too easily comes up with fast and stunning bits of pithy truth telling from which there is no response. It comes off as stunningly cliched TV drama, and I think Huffington Post was on reasonable grounds to doubt the veracity of the author's account of the meeting. Still, it's worth a read to glean the essential truth herin, that deserving artists are being cheated by the service . Spotify , from what I understand, is "making bank", as the kids say, and can well afford to pay these good people what their work is worth. Also, checking out the author's"I Respect Music" Website can help, perhaps, move the needle in the right direction.

The sublime "The Shape of Water"

That is, there is no shortage of f-bombs. Also done incredibly well is handling the sexual element that's usually obscured by sentiment and courtly sentiments; del Toro brings this aspect, and the entire premise, into a world we recognize, in this case, the early 60s in Baltimore. Time, place, inference, and the use of nicely chosen incidental details and art design set up the way the tale is conveyed. Most importantly, there is a human connection here, with the theme of loneliness being a primal driving force to seek love or revenge superbly embodied in fully rounded characters.

Visually, this is your typical del Toro production, with the deep, rich, dark color scheme, seamless editing, controlled and adequate contrast between the more human and banal world of the 60s and the more fantastical, menacing interiors of the more sci-fi sequences. Stand out performances from Michael Shannon, a grand and messed up baddie, and Richard Jenkins, who seems incapable of doing bad work.

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

These chops don't cut deep enough

Patrick Yandall would one of those jazz-inflected guitarists I would usually go nuts over.The qualifier "usually" gives you a hint of what I thought of his new album A Journey Home. The San Diego-based musician is a veteran of the scene, active since the ’90s in many bands and collaborative efforts, and has released 20 albums of his music. His productive longevity is understandable, considering that Yandall is an excellent guitarist, potentially a great one. He is a master of groove, tone, and feel, a fret man able to fill space with Wes Montgomery-like octave chords, punctuate the beats with short blues riffs and , and, when the feeling merits, let loose with an impressive flurry of runs. In its best moments—and there are many sweet spots on this disc—his soloing transcends the often repetitive and simplistic structures of his self-penned material. After the fact, the grooves lack personality; they are placeholders, more or less, existing less to push Yandall than they to keep his chops from getting too hairy for the average listener. The guitarist restricts himself , keeps himself in check, careful not to offend. The conservative approach creates conservative results.In another discussion, we might call it being chintzy with the available bounty. A guitarist as technically gifted and as fluidly expressive as Yandall ought to be leaping over such barriers and cutting loose for real on a track or two. Stronger, more varied, more intricate compositions would aid toward that goal, if Yandall were so inclined. The songs on A Journey Home are simple, hardly a sin, and there are some good melodic ideas here,.But there is a formula smooth-jazz/light funk motif they fall into, with incidental keyboards, synths providing a few pale shades of color, an occasional piano solo (played by Yandall, who, as I understand, plays all the instruments). The drum tracks, honestly, are without soul. The burden falls to Yandall’s obvious virtuosity, which raises to the occasion on several tracks, especially on “Passion,” a Latin groove where the artist unleashes what he can do; hot riffs, screaming ostinatos, raging note clusters. But alas, it is too short a solo, as it fades and we return again to the album’s steadfast sameness, waiting for another moment when the guitarist steps into the spotlight again. You might find yourself fighting an urge to fast forward through a mostly indifferent set of rhythm tracks to find some places where the music starts to cook again. Well, the guitarist anyway, if not the actual tunes to composed to hang his virtuosity on. Agreeably, Yandall, does a good turn with the last track . a stone cold blues shuffle, “Blue Jay Blues,” highlighting a glorious walking bass, and a pulverizing solo from Yandall, with brief and sharp assertions, serpentine runs weaving between the one-four-five beats, some bittersweet BB King-like vibrato. This track is a rousing, strutting jam. One wants more.This ought to have been an outstanding album. As is, it is only good one, buoyed by Yandall’s spirited playing. A musician this gifted deserves the energy and inspiration an actual band of musicians can provide, and the improvisatory possibilities better material can provide.

(This was published in slightlydifferent form in the San Diego Troubadour. Used with kind permission)

Thursday, December 28, 2017

Show some grit for the MC5

(In the spirit of Lester Bangs, exaggerated even by his standards, I wrote this fever dream as a tirade demanding the induction of the MC5 into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It occurs to me that the 5, in their prime, could give a damn about such a corporately bestowed honor. Still, I thought this should have a home on this blog as well.-tb)

Wednesday, December 27, 2017

Name Brand Kvetching

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-9672184-1484526024-8131.jpeg.jpg)

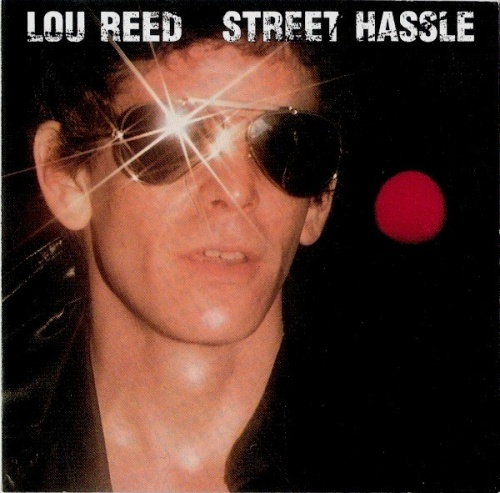

Lou Reed’s Street Hassle or David Bowie’s Station to Station, which album do prefer, love more, pick if you were going to be stranded on a desert island? A question to that effect appeared on one of the odd corners I visit on the internet looking for intelligent conversation on art and matters of concern that cannot be calculated by conventional metrics of worth. So, an interesting question, even if the choice between two superb albums makes one asks why these two, which are wildly dissimilar in their respective greatness. Compare and contrast? Perhaps Reed’s album New York, his inspired two-sided screed against the insoluble cruelty that inhabits the deeper and darker corners of a great city, compared and contrasted against Bowie’s Tin Machine project, an angular, Cubist kind of hard rock rage highlighting Bowie’s theatrical pronouncements against human creation of a misery index set against and appealing assault of shrapnel percussion and blood splatter guitar work? A more focused conversation, perhaps, but I remained with the question that was posted.I would choose Street Hassle if one desires street credibility and genuine amounts of poetic brilliance, both of which Reed despite his well-known habit of overestimating his overall musical genius. His musical punch was from his words wedded with the simple, scraping movement of his chords wedded with his especially acute and minimalistic detailing of lives in the streets, the doorways, the alleys of New York and its vast underbelly of fallen souls. Reed, at his best, had a feel for the characters in these unapologetic environs--sympathetic but not glorifying, poetic but not conventionally "beautiful" by more timid sensibilities--and on Street Hassle his greatest virtues, as such, are in full force. Reed was a writer before anything else, living in the shadows of a city that punished its geniuses with poverty, drug addiction and the contempt of the public, the authorities, and even the cast of good souls charged with taking care of them. This was fine with Reed and many of his cohorts; he was a man in the city, a maker of an invisible scene where the atonal heart of the experimental arts were in a social sphere so on the outs with whatever the hip community imagined itself as being that even the most vocally revolutionary of the millionaire rock and rollers and painters and filmmakers of the period wished they would simply evaporate and vanish in a dissipating gust of steam. Reed, Herbert Huncke, Burroughs, Henry Miller, in the belly of the beast, writing poetry, drinking, talking, painting at the outskirts of high towers of a city that provided with cold water flats and long, cold shadows to hide within. This is what Reed saw, wrote about, live amongst.

Lou Reed’s Street Hassle or David Bowie’s Station to Station, which album do prefer, love more, pick if you were going to be stranded on a desert island? A question to that effect appeared on one of the odd corners I visit on the internet looking for intelligent conversation on art and matters of concern that cannot be calculated by conventional metrics of worth. So, an interesting question, even if the choice between two superb albums makes one asks why these two, which are wildly dissimilar in their respective greatness. Compare and contrast? Perhaps Reed’s album New York, his inspired two-sided screed against the insoluble cruelty that inhabits the deeper and darker corners of a great city, compared and contrasted against Bowie’s Tin Machine project, an angular, Cubist kind of hard rock rage highlighting Bowie’s theatrical pronouncements against human creation of a misery index set against and appealing assault of shrapnel percussion and blood splatter guitar work? A more focused conversation, perhaps, but I remained with the question that was posted.I would choose Street Hassle if one desires street credibility and genuine amounts of poetic brilliance, both of which Reed despite his well-known habit of overestimating his overall musical genius. His musical punch was from his words wedded with the simple, scraping movement of his chords wedded with his especially acute and minimalistic detailing of lives in the streets, the doorways, the alleys of New York and its vast underbelly of fallen souls. Reed, at his best, had a feel for the characters in these unapologetic environs--sympathetic but not glorifying, poetic but not conventionally "beautiful" by more timid sensibilities--and on Street Hassle his greatest virtues, as such, are in full force. Reed was a writer before anything else, living in the shadows of a city that punished its geniuses with poverty, drug addiction and the contempt of the public, the authorities, and even the cast of good souls charged with taking care of them. This was fine with Reed and many of his cohorts; he was a man in the city, a maker of an invisible scene where the atonal heart of the experimental arts were in a social sphere so on the outs with whatever the hip community imagined itself as being that even the most vocally revolutionary of the millionaire rock and rollers and painters and filmmakers of the period wished they would simply evaporate and vanish in a dissipating gust of steam. Reed, Herbert Huncke, Burroughs, Henry Miller, in the belly of the beast, writing poetry, drinking, talking, painting at the outskirts of high towers of a city that provided with cold water flats and long, cold shadows to hide within. This is what Reed saw, wrote about, live amongst.

Bowie wanted some of that, to be all of that, but he was a tourist and didn’t stop being a mere borrower until Station to Station. Bowie coveted that kind of brutalism, evident in his band Tin Machine, which tried to be street, noisy and savant gardish in the shrieking sense of the Velvet Underground but which were undermined by Bowie's autodidactic habits and Anthony Newlyesque vocalisms, reminding you that he was, above all else, an actor. Bowie’s overt theatricality often made me roll my eyes, but he was a man who knew how to turn what can be used against him critically into an asset that elevates his art when his inspiration moves him to do so. He was a far superior synthesizer of many styles and moods and texture and had a genius for texture and color in the studio. Philip Glass, Brian Eno, funk, disco beats and plenty of chomping, comping guitar made this a revolutionary fusion masterpiece; Bowie, as well, reined in his persona to a dimension that suited him, that of a post WW2 soul,,, weary unto death, a witness to yet another large and irreparable crack in the foundations of a great and honored culture and attending traditions. Bowie was always musically more ambitious than Reed. That's pretty self-evident and not really worth the bother to point out unless your preference is competence over the kind of brutalism Reed specialized in. Reed's lyrics, in my view, have a substantial edge over Bowie, who was plagued by a prevailing sense of who wanted to sound like.

The atmospherics and production garnishes of Station to Station did free Bowie from any obligation to sound like he was trying to say anything that could be interpreted as philosophical. His words became more diffuse, full of associative leaps, ellipsis, images that were and remain private mysteries so far as what they reference but which provide a rich and vaguely mystical and definitely European tone to the inspired constructions he released from this point onward. As a lyricist, as a writer, as a storyteller, Reed was the authentic genius here; he was a blend of a mind that made equal use of his library card and his street smarts and provided a skill to be expansive while maintaining a hard, stripped-down veneer. Bowie the tourist became Bowie the innovator with Station to Station and, in his way, achieved parity with Reed as an expressive artist.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-

Why Bob Seger isn't as highly praised as Springsteen is worth asking, and it comes down to something as shallow as Springsteen being t...