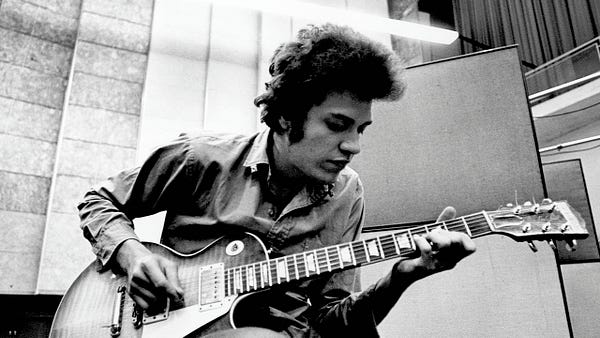

This is more in wondering what ever happened to the memory of the band’s first guitarist, the late Mike Bloomfield. Bloomfield was a white boy, born in Chicago, from the suburbs, who was in love with black Chicago blues and traveled to Southside Chicago to witness the music he loved in the black clubs where they played: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Hubert Sumlin. I knew next to nil about the blues then nor did I know who Bloomfield’s influences and mentors were. What I did know was that he played guitar like nothing I had encountered until then.

Biting, fluid, aching, and bittersweet, Bloomfield was masterful that night, a scrawny, jerky Jewish kid playing a black man’s blues with an intensity that was absent of cliché or recycled rockabilly riffs; what he was doing was something else. I was converted to the blues and the cause of lauding Bloomfield each chance I had with fellow music geeks. He recorded two widely praised albums with the Butterfield Band,

Introducing the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and

East West. Just as things began to break for the band, Bloomfield did what became a predictable habit throughout his career, he abruptly left the band. He started one of the first rock-oriented horn bands — the Electric Flag — leading a racially diverse group of musicians through a variety of American music that include blues, jazz, rockabilly, and soul.

A Long Time Coming, their first album, was well reviewed and again, just as things began to percolate, Bloomfield bailed on the project and wound up recording with Blood, Sweat and Tears founder Al Kooper for the

Super Session album. Mike Bloomfield, though, couldn’t finish the album and left the project after recording half an album’s worth of splendid guitar work, with Kooper enlisting the aid of guitarist Steve Stills to finish the disc.

And so it was, a genius guitarist who was easily a decade ahead of his time with regard to the art of rock guitar, leaving one promising band and collaboration after another, impatient, a walking case of the jitters. He couldn’t stay in one place too long.

My family moved to San Diego in the summer of 1969, during the Woodstock Festival, and, as it turned out over the years, Mike Bloomfield was a frequent visitor to the area during the 1970s, playing with an assortment of friends at colleges and clubs to promote whatever album he’d just released, or merely picking up a date because he still had name recognition even in music that was becoming increasingly corporate and predictable in a broad range of commercial releases. Bloomfield’s gigs promised the loose-fitting grit of the Bay Area style as well as a funky blend of folk, blues, jazz, and Eastern influences that ran contrary to the tight shoes record companies and radio stations were increasingly insisting musical artists wear in order to gain exposure. Bloomfield had done his best to sabotage his commercial potential by his erratic behavior and inconsistent performances, but there was something intriguing about Bloomfield’s live performances; you didn’t know how well Bloomfield would play, inspired and ruling the frets like the master he could be or so distracted and disassembled that his musicianship would make those unaware of what he could do wonder loudly and angrily what the big deal was with his reputedly great musician.

Apprehension over pending Bloomfield gigs was understandable, considering that his swings in mood and delivery made the interested fan wonder out loud which Mike Bloomfield would show up, the wonderfully expressive blues player who was one of the ground-zero white players to introduce blues, jazz, and raga and improvisational charms into rock ’n’ roll’s evolving instrumental style, or the mercurial bright boy who couldn’t stay in one place, stay in his seat, finish what he’d started? I’ve seen both in San Diego venues, hither and yon, the results different as old steak and the freshest, sweetest fruit.

It sorts of works out as a story of two university engagements, the night and day, the sweet and stinky, the great and the gross.

In the early 1970s, Bloomfield and Friends played a concert at the University of San Diego gym ,the first time I’d have a chance to see him live since Detroit; he was magnificent and everything critics and admirers claimed him to be. Energetic, even smiling, a change from his usually scrunched up scowl as he punished the guitar strings. The music consisted of up-tempo shuffles and rhythm and blues chestnuts, slow, heartbreaking blues and some instances of the fleeting jazz/raga improvisations Bloomfield introduced to the larger world, which was still living within the confines of Top 40 radio. There was always something simultaneously graceful and unwieldy about Bloomfield’s manner of playing; blessed with a fluidity that was uncommon in the day for rock-oriented guitarists, Bloomfield’s habit was to use everything he had when he sallied forth on a long solo. His slow blues would begin with the bittersweet and golden-hued tone of B.B. King — a sublime replication of the human voice. He would seem to lose control of his stream and have his phrases go over the 1–1V-V progression and wander into dissonance and near atonality as though channeling Coltrane’s high-register skirmishes.

After that, he would bring it back to the V chord, his playing deeper, with a long, searing blues bend sustained for several measures as the pitch increased higher in tone and intensity until he released the note and altered the mood again with softer, whispering phrases that brought the blues to a finely buffered resolution. It wasn’t all slow blues and bathos, though, and I remember how amazingly Bloomfield made the up-tempo blues stomp and rock under the snapping lash of his hot-tempered lead work, or how he displayed a knack for rapid, single-note runs during jazzier instrumentals, highlighted by the full, ringing octaves pioneered by Wes Montgomery. It was a good night for Bloomfield, a good night for the blues. Bloomfield, though, needed to keep moving after the show. He was quickly gone, seen rushing out of the gym’s side door holding his guitar case, brusquely brushing past fans trying to shake his hand or give him high fives or something stronger. He was in a hurry to get somewhere.

The memory gets blurry again recollecting another Bloomfield concert, a reunion concert not so long after the show in the USD Gym. I can’t recall the date, but I do remember what happened.

The Electric Flag, the band that Bloomfield formed after his departure from the Butterfield group, leaving promptly after their widely praised first album. Moby Grape also played, a fantastically talented group of musicians that arose toward the end of the San Francisco rock era and produced two worthy albums. Moby Grape and Wow, before their rapid decline due to drug problems and member struggles with mental illness, were scheduled for a double-whammy reunion concert on a date in the mid-’70s at the UCSD Gym. There was a good amount of commotion among my fellow music obsessives, mad chatter over beers and bongs about how this would shake out. Two bands of short life spans but worthy discographies on tour together, attempting again to be relevant in a terrain that was rapidly forgetting the magic and value of the hippie vibe.

Moby Grape’s performance was, to be kind, something resembling an arrangement of mannequins dressed as old bohemians that held guitars while music was piped in through a scratchy PA system.

A desultory display all around, the band sometimes came to life with a snappy guitar riff or unexpected burst of energy from the rhythm section, but there was the element of songs sagging in the middle, the musicians fall out of time with each other, of lyrics being forgotten, missed cues. The harmonies were ragged, a moth eaten weave of voices. That night Moby Grape’s fine legacy was a burden, a standard they couldn’t come to terms with.

Some of the crowd liked it though, but the applause and war-howls was as lackluster as the music. It was an open seating affair, which meant audience members found their patch of hard wood floor and made themselves comfortable amid the other attendees who had the same idea, to get as near the stage as possible and commune with the drum beats, guitar solos, and the passing of ignitable drugs. The lights remained low during the break between bands; I could see the cherry tips of joints floating in air, passed finger tips to fingertips, and the room was filled with the noxious aromas of marijuana reeking sweet. But the rule was this: stay for Bloomfield, the First Guitar Hero, the erratic genius of electric blues and roots music.

It was a pensive wait for the Electric Flag’s arrival on stage, as the squatting student audience, cooling their heels between bio chem exams and writing padded term papers notable for turgid prose and jargonalia, started a murmur of sorts, people yelling out “Bloomfield” or the staid and sturdy “rock ’n’ roll,” voices hoarse with the burn of pot. A Frisbee was being tossed about. There was the tangible feeling that one was a sardine in a can.

The Electric Flag soon took the stage, first the horn section, all proper looking gents dressed for the gig, alert and seemingly sober, and then the others, the bassist and keyboardist. Drummer Buddy Miles came on and took his place behind a large drum set, ready to let the world know again how it was he’d been picked by Jimi Hendrix, John McLaughlin, Carlos Santana, and Bloomfield to handle the sticks on various projects. Miles was a good, not great drummer, able to adjust his rhythm and blues approach to a variety of rhythmic requirements, minimal but firm, steady, on the mark. He was not a Tony Williams, not a Mitch Mitchell, but he got the job done. His second biggest talent seemed to be skill at landing high-profile gigs with famous rock guitarists. Then vocalist Nick Gravenites took his position, an underrated vocalist and the composer of the blues standard “Born in Chicago,” made famous by the Butterfield Blues Band.

Finally, Bloomfield himself emerged, thin, lanky, jeans drooping and back curved, looking not a little like a guitar bearing pugilist approaching his opponent, sensing where the next punch was coming from. There was a good amount of applause and this time the gymnasium echoed with the fanfare, as much from the relief of the waiting as it was anticipation for Bloomfield’s artistry. The performance itself was wanting, though, not bad nor slovenly, but strangely professional. In the metaphysics of judging such things, or at least reconsidering the events years removed, that secret something was missing: the elan, the verve, the energy that comes from playing the notes in such a way that the nervous system lights up like Christmas lights and infuses the sounds with a feeling that resonates in a listener in areas of the soul that have nothing to do with the quality of technique. The band, musically on point, could have been employees gathered to collect their paychecks after a Friday shift. Bloomfield wasn’t having a good time of it and seemed hesitant to play anything.

Where the band would play a solid, Albert King-style blues requiring suitably mournful and sting guitar fills between phrases, Bloomfield was often silent or late to the cue, and his solos were tentative half the time, as if he were trying to remember why he was in the center of the stage in the spotlight. He did play a great solo on the band’s signature song “Texas,” a moment when talent and sensibility jibed and made something moving, a slow blues solo as very few people could play it. This was half way through the show and it made me optimistic that the rest of the night would ascend to the proper heights of excellence. One could here, though, electrical crackling and short bursts of electronic blurting from Bloomfield’s amp.

He was agitated; his face was a road map of exasperated furrows. Two songs later the band went into a slow soul ballad featuring Buddy Miles on drums. Bloomfield strummed away in accompaniment while Miles softly drummed and crooned the lyrics. Miles, who had a voice that was, say, adequate to sing in harmony but far too thin and screechy to take on the Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, or Wilson Pickett gospel-influenced style, had walked up from behind his drum kit and took the microphone from the stand, confessing to the crowd on why he needed his baby. It became an endurance contest but Bloomfield couldn’t take it. His amp continued producing extracurricular belches and his facial features vanished behind a mask of irritation. He abruptly yanked the cord from his amp and walked off the stage, not to return. The rest of the Electric Flag managed as best they could but by that point one could seem a growing stream of students, hippies, faculty and assorted bohemians headed for the exits, heading to the parked cars or buses that awaited them, wondering what happened to Bloomfield and if they could get a refund.

This was the deal one made with their admiration of Bloomfield’s guitar work — that one would either be in the presence of a master, an innovator, a man who changed the way succeeding guitarists approached the way they played guitar, or be witness to a burned-out case. Michael Bloomfield was found dead of an apparent drug overdose February 15, 1981, in the front seat of his Mercedes. He was a heroin user and suffered, it’s been said, from chronic insomnia, two things that might provide clues to the musician’s famed inconsistency. For all his breakthroughs in revolutionizing rock-oriented guitar playing with a heady fusion of blues, jazz, swing, raga and traditional folk-blues techniques, Mike Bloomfield was a man who didn’t stay with a project for very long, as his brief but galvanizing stints with Paul Butterfield and the Electric Flag and Al Kooper attest. Other projects, such his collaboration with Dr. John and John Hammond Jr. in the trio Triumvirate, didn’t go beyond one album and one tour. Another band called KGB with Ric Grech (from Family and Blind Faith), Barry Goldberg (Butterfield) , Carmine Appice (Vanilla Fudge, Jeff Beck, Rod Stewart) and Ray Kennedy (James Gang) was an attempt to put a “super group” together, but , again, didn’t last beyond one album. Bloomfield did, though, keep busy with his music, appearing on a good number of albums by other musicians, and releasing a steady stream of studio albums of his own where his best skills were displayed.

It’d be a little grandiose to maintain that Bloomfield is the Forgotten Guitar Hero, but it irksome to those of us in the early circles of fans to hear younger blues fans discuss the genius of Stevie Ray Vaughn or Robin Trower and the like without a mention of MBs monumental importance to establishing blues as the Rosetta stone through which all contemporary rock guitar playing comes from. Under discussed, obscured, perhaps, but not forgotten, not wholly.

One day few years ago I was at La Jolla’s Pannikin Café on Girard Ave., next to DG Wills bookstore, and there were the familiar plaintive, slicing, fluid riffs of Mike Bloomfield coming out from behind the counter. It was turned up loud, like it should be; I could hear the notes emoting from across the street as I waited for the traffic light to change. John, a fine young man with an angelic crest of long brown hair, was the manager on duty and the Bloomfield disc, 1969‘s Live at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West, was his choice of play. I ordered my coffee, black, no sugar, no room for cream, and asked him if he liked Bloomfield.

“Oh yeah” he replied. He took my money, gave me change. I threw the coins into the tip can.

“You know how old this recording is?” I asked, hoping to brag with one of those back-in-the-day boasts that maintained that the past was better than what’s being sold in the current time. John just smiled and ended the conversation with the best response regarding the matter.

“Really doesn’t matter” he said, “it sounds great right now.”