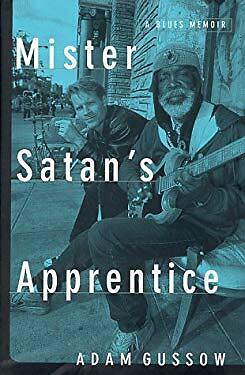

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1766995-1516656517-3547.jpeg.jpg) Sterling Magee, half of the stellar blues duo Satan and Adam, has passed away.It was just announced on Mr. Magee's Facebook page that he "...passed away peacefully last night." No other details. This is tremendously sad news. As a musician, I think he was without peer, and I cannot think of anyone I've heard who has done the one-man-band street musician project as brilliantly or resourcefully as he had done. As part of Satan and Adam, his guitar work was rhythmic and forceful, and the time he kept on his customized drum set up (with cymbals!) unfailingly created grooves and moods and such that complimented his gruff, splintery, exclamatory singing.

Sterling Magee, half of the stellar blues duo Satan and Adam, has passed away.It was just announced on Mr. Magee's Facebook page that he "...passed away peacefully last night." No other details. This is tremendously sad news. As a musician, I think he was without peer, and I cannot think of anyone I've heard who has done the one-man-band street musician project as brilliantly or resourcefully as he had done. As part of Satan and Adam, his guitar work was rhythmic and forceful, and the time he kept on his customized drum set up (with cymbals!) unfailingly created grooves and moods and such that complimented his gruff, splintery, exclamatory singing. Monday, September 7, 2020

STERLING MAGEE OF SATAN AND ADAM, RIP

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1766995-1516656517-3547.jpeg.jpg) Sterling Magee, half of the stellar blues duo Satan and Adam, has passed away.It was just announced on Mr. Magee's Facebook page that he "...passed away peacefully last night." No other details. This is tremendously sad news. As a musician, I think he was without peer, and I cannot think of anyone I've heard who has done the one-man-band street musician project as brilliantly or resourcefully as he had done. As part of Satan and Adam, his guitar work was rhythmic and forceful, and the time he kept on his customized drum set up (with cymbals!) unfailingly created grooves and moods and such that complimented his gruff, splintery, exclamatory singing.

Sterling Magee, half of the stellar blues duo Satan and Adam, has passed away.It was just announced on Mr. Magee's Facebook page that he "...passed away peacefully last night." No other details. This is tremendously sad news. As a musician, I think he was without peer, and I cannot think of anyone I've heard who has done the one-man-band street musician project as brilliantly or resourcefully as he had done. As part of Satan and Adam, his guitar work was rhythmic and forceful, and the time he kept on his customized drum set up (with cymbals!) unfailingly created grooves and moods and such that complimented his gruff, splintery, exclamatory singing. Saturday, September 5, 2020

AYN RAND WAS A TERRIBLE WRITER AND A HORRIBLE HUMAN BEING

LONG WINDED AND GLIB ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ASKED OF ME ON QUORA

“ (1)…the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.

“(2)…the various branches of creative activity, such as painting, music, literature, and dance.”

Thursday, August 27, 2020

THE LONG WINDED

I can assure you, sir, that these things really suck!" -- Don Van Vliet,when selling a vacuum cleaner to Aldous Huxley

|

| Image by mikeable10 |

No , you’re neither drudge nor dullard for not being drawn to Don DeLillo. He either appeals to you or he doesn’t, as is the case with any other serious (or less serious) writer who wants to get your attention. The charges that DeLillo is tedious, wordy, and pretentious, not necessarily in that order, are themselves tedious and , it seems, levied by folks who either haven’t read much of the author, more likely, put forward by a host of soreheads who use DeLillo as a representative of a kind of fiction writing they dismiss wholesale. I’m not an easy sell when it comes to be seduced by writer’s reputations — my friends accuse me of being too picky, too “critical” — but I’ve read most of DeLillo’s fifteen novels since I discovered him in the early Seventies; if I didn’t find his writing brilliant and vibrant or found his narrative ruminations on the frayed American spirit engaging, I’d not have bothered with him. DeLillo is a serious writer, sober as a brick, but he is not pompous.

I marveled at the economy of his writing. He does write long sentences in parts of his novels, but they are so precisely presented they seem positively succinct. And that, I think, is a large part of their power. There are some readers who are slightly stunned when it’s revealed that one of DeLillo’s avowed influences , a model to learn from , is Ernest Hemingway, who’s low-modifier, low-simile, spare and sharp focused prose is detectable even those writers noted for their compound sentences. It would seem to be a matter of not the length of the sentence itself, but with the precision of the words being applied, the practice where typing and jotting things down becomes actual writing, that is, composition, a state of bring elements together that makes the expression comprehensible (shall we add “relatable”?) to readers besides the author and his or her immediate circle. Power and purpose are the things that make a long sentence of fiction a thing of wonder;good sentences are like pieces of great music that you read again, listen to once more. The Godfather of the terse, abrupt phrase, Hemingway could, when he chose to , compose a long sentence that had the advantage of serpentine rhythms snaking their way around a nettlesome gather of conflicting emotions and sentiments, but still had a wallop of an adroitly worded police report. The longest sentence he ever wrote, 424 words in his story “The Green Hills of Africa” is cinematic in its sweep:

That something I cannot yet define completely but the feeling comes when you write well and truly of something and know impersonally you have written in that way and those who are paid to read it and report on it do not like the subject so they say it is all a fake, yet you know its value absolutely; or when you do something which people do not consider a serious occupation and yet you know truly, that it is as important and has always been as important as all the things that are in fashion, and when, on the sea, you are alone with it and know that this Gulf Stream you are living with, knowing, learning about, and loving, has moved, as it moves, since before man, and that it has gone by the shoreline of that long, beautiful, unhappy island since before Columbus sighted it and that the things you find out about it, and those that have always lived in it are permanent and of value because that stream will flow, as it has flowed, after the Indians, after the Spaniards, after the British, after the Americans and after all the Cubans and all the systems of governments, the richness, the poverty, the martyrdom, the sacrifice and the venality and the cruelty are all gone as the high-piled scow of garbage, bright-colored, white-flecked, ill-smelling, now tilted on its side, spills off its load into the blue water, turning it a pale green to a depth of four or five fathoms as the load spreads across the surface, the sinkable part going down and the flotsam of palm fronds, corks, bottles, and used electric light globes, seasoned with an occasional condom or a deep floating corset, the torn leaves of a student’s exercise book, a well-inflated dog, the occasional rat, the no-longer-distinguished cat; all this well shepherded by the boats of the garbage pickers who pluck their prizes with long poles, as interested, as intelligent, and as accurate as historians; they have the viewpoint; the stream, with no visible flow, takes five loads of this a day when things are going well in La Habana and in ten miles along the coast it is as clear and blue and unimpressed as it was ever before the tug hauled out the scow; and the palm fronds of our victories, the worn light bulbs of our discoveries and the empty condoms of our great loves float with no significance against one single, lasting thing — -the stream.

The sentence approaches the state of pure lyric poetry, where the facts of what the senses reveal to us about the part of the world a character inhabits and finds intimacy with pass by in a rapid, camera like sweep, a suggestion of motion that brings about fast and fleeting descriptions, associations and swift suggestions of emotional attachment . The scene is both familiar as family yet made strange in the recollection, as a character’s subsequent history disrupts an instinctive nostalgia and provides an undertone of rueful irony , a sense of things not taken up. This is a fascinating case of recollection examined both as Eden and , maybe, a ring in the concentric circles of a hell formed by a character’s own decisions and choices. For the sheer joy of reading the next passage, let’s take a look at a longish sentence from DeLillo’s Underworld, where a character is driving, and manages to discern the roads, the highways, the freeway system as an ecosystem . DeLillo allows himself to riff on the theme, and to encroach just slightly on a rant, but the sentence , like many other passages in the sprawling genius of Underworld, is from a master who knows something about the mystery that comes from the not getting it right avails us of the heart-stopping poetics that momentarily cause us to reflect on our history of acting in our exclusive interest.

He drove into the spewing smoke of acres of burning truck tires and the planes descended and the transit cranes stood in rows at the marine terminal and he saw billboards for Hertz and Avis and Chevy Blazer, for Marlboro, Continental and Goodyear, and he realized that all the things around him, the planes taking off and landing, the streaking cars, the tires on the cars, the cigarettes that the drivers of the cars were dousing in their ashtrays — all these were on the billboards around him, systematically linked in some self-referring relationship that had a kind of neurotic tightness, an inescapability, as if the billboards were generating reality…

I think there’s a clutch of otherwise smart people who distrust and actively dislike anything that suggests elegant or lyric prose writing. John Updike, who, I think, was perhaps the most consistently brilliant and resourceful American novelists until his death, was routinely pilloried for the seamless flow of his telling details. If one cares to do a survey, I suspect they’d find the same caustic template levied at other writers who are noted for their ability to detail the worlds they imagine in ways that make the mundane take on a new resonance. Nabokov, DeLillo, Henry James, Richard Powers have all been assessed by a noisy few as being “too wordy”. The sourpusses seem to forget that this fiction, not journalism, that this literature, no police reports. The secret, I think, is that a writer possessed of a fluid style manages to link their mastery of the language with the firm outlining of the collective personalities of the characters , both major and minor.

The elegance is in service to a psychological dimension that otherwise might not be available. The thinking among the anti-elegance crowd is that writing must be grunts, groans and monosyllabic bleats, a perversion of the modernist notion that words are objects as used as materials to get to the essential nature of the material world. Lucky for us that no one convincingly defined what “essential nature” was, leaving those readers who love run-on sentences with more recent examples of the word drunk in progress. I don’t mind long sentences as long as there is some kind of mastery of the voice a writer might attempt at length; I am fond of Whitman, Henry James, Norman Mailer, David Foster Wallace and Joyce Carol Oates, writers who manage poetry in their long-winded ways. That is to say, they didn’t sound phony, and the rhythms sounded like genuine expressions of personalities given to subtle word choice. Kerouac, though, struck me as tone-deaf. After all these years of complaining about his style, or his attempts at style, the issue may be no more than a matter of taste. Jack Kerouac is nearly in our American Canon, and one must remember that the sort of idiom that constitutes literary language constantly changes over the centuries; language is a living thing, as it must be for literature to remain relevant as a practice and preference generation to generation.

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Briefly, Two Novels by Richard Powers

The Echo Maker has been called an "post 911 novel",a description that seems to fit in that its central metaphor is the yearning for a time before life became problematic.But that's too pat a description, and it cheats against Power's on going themes of characters trying to reintegrate themselves into what they view as an ideal past they've either been torn from, had ignored until they were older and hobbled with responsibility and ailments, or were denied outright. There's some things in common with Don DeLillo, as in how a constructed reality and the narratives we create to give them to give them weight, but DeLillo, despite his frequent beauty, hasn't Powers' heart. The Echo Maker makes me think of a comedy routine where the comedian posits "I went to bed last night and when I woke up everything around me had been replaced with exact replicas".The comedy routine was funny, the novel is tragic, but they share the same premise, finding yourself stuck in a skin where nothing around appears false, a world of impostured objects. Family crisis time, of course, as neither Karin nor Mark having especially heroic lives to begin with, suddenly tossed by circumstance into a medical dilemma where the desired , dreamed of outcome would be a return to the banal life that existed prior to the accident. Powers shares with DeLillo the ability to wax lyric on the familiar world and make it appear strange, foreboding, erotic, fancying a semiological turn as the associations with the objects and places fade and the remains of memory become a forlorn poetry. But again, Powers has the younger, bigger heart than DeLillo's magisterial detachment, and we appreciate quietly conveyed message; pay attention to the moment you're in, make note of what's important, do something with what you have. Not to do so invites regret and final years of wondering what happened during the time in the middle of life.

The Echo Maker has been called an "post 911 novel",a description that seems to fit in that its central metaphor is the yearning for a time before life became problematic.But that's too pat a description, and it cheats against Power's on going themes of characters trying to reintegrate themselves into what they view as an ideal past they've either been torn from, had ignored until they were older and hobbled with responsibility and ailments, or were denied outright. There's some things in common with Don DeLillo, as in how a constructed reality and the narratives we create to give them to give them weight, but DeLillo, despite his frequent beauty, hasn't Powers' heart. The Echo Maker makes me think of a comedy routine where the comedian posits "I went to bed last night and when I woke up everything around me had been replaced with exact replicas".The comedy routine was funny, the novel is tragic, but they share the same premise, finding yourself stuck in a skin where nothing around appears false, a world of impostured objects. Family crisis time, of course, as neither Karin nor Mark having especially heroic lives to begin with, suddenly tossed by circumstance into a medical dilemma where the desired , dreamed of outcome would be a return to the banal life that existed prior to the accident. Powers shares with DeLillo the ability to wax lyric on the familiar world and make it appear strange, foreboding, erotic, fancying a semiological turn as the associations with the objects and places fade and the remains of memory become a forlorn poetry. But again, Powers has the younger, bigger heart than DeLillo's magisterial detachment, and we appreciate quietly conveyed message; pay attention to the moment you're in, make note of what's important, do something with what you have. Not to do so invites regret and final years of wondering what happened during the time in the middle of life. Staring at the Spines of Some John Updike Titles on a Book Shelf: a very brief appreciation

Tuesday, August 18, 2020

HIGHWAY 61 REVISITED

Everyone seems to start and end at different places, tempos are ragged, sometimes tentative, the pace is bludgeoning, the instruments are often out of tune, and its all glorious,brilliant Dylan in the middle of it all, snarling, burning through his genius and abusing his muse for the greater glory of what would become a definitive record. It is raw and spiky and gives you a perspective that says that there is no proof because there is no pudding.You'd be right, I suppose , in linking Dylan's early cynicism about the motives of people and the institutions they represent to his dalliance of brimstone Christianity. It does seem a natural progression, although I've expanded my view on is SLOW TRAIN COMING album and would equate it closer to the fatalistic Christianity of Flannery O'Connor, a writer who was obsessed with the vision of Christ, the afterlife, as a strange way of thinking that you've cut the spiritual requirements to sit at God's right or left hand,which ever comes first. Her's was a body of thinking about Christianity that was too weird and personal to be of any use to any to anyone except those readers of American Southern fiction who marveled at the writer's skill at imagining the worst while dealing, even in submerged form, on matters of Belief.Her measure of Christian love was a love of Christ himself, not so much for the fellow man.

-

Why Bob Seger isn't as highly praised as Springsteen is worth asking, and it comes down to something as shallow as Springsteen being t...

-

The firing of pop music Robert Christgau from the Village Voice by their new owners gives me yet another reason to pass up the weekly on the...