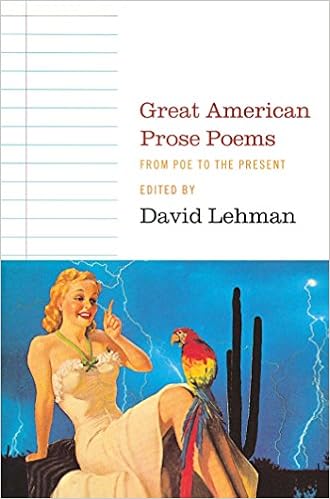

BOP APOCALYPSE:

Jazz, Race, Drugs, and the Beats

By Martin Torgoff

(Da Capo Press)

Bop, Apocalypse: Jazz, Race, Drugs, and Jazz is a large and lumbering subject, jazz musicians, drugs and the Beats, but author Martin Torgoff soft-pedals his main thesis--that drugs were an essential ingredient in the creation of bold new music and writing from black musicians and white writers--with a mostly light touch.. Instead of weighing his subject an overarching and cliché- burdened theory, Bop Apocalypse at its best provides us with an anecdotal history, a narrative that jumps through time, cutting between jazz musicians and beat writers, in a series of essays and recollections that seek the precise moment when the artists were introduced to drugs and, more emphatically, how drugs motivated musicians and poets alike to challenge themselves to create new, nerve rattling work. The book doesn’t quite escape the grasp of received perceptions about creativity and the need of the outsider genius to derange themselves to achieve perceptions greater than the masses could collectively handle—you suspect at times that Torgoff took Aldous Huxley’s utopian dreams in Doors of Perception at face value and since operated as if that author’s erudite daydreaming had become an actual fact of existence – but if one can suspend cynicism even slightly, there are some good stories to read here.

Those expecting a continuous timeline will find this book a bit exasperating, as Torgoff prefers to present his history and his argument in something of a cinematic style, with jump cuts, flashbacks and fast-forwards. There is the sense of him attempting an impressionistic approach to how particular events are linked to creating the mythos we've come to create hip culture. It's a fractured, frustrating but fascinating narrative all the same, dealing with the creation of an outlaw culture with the federal criminalization of Marijuana by the efforts of Harry J. Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics back in the day and the efforts of law enforcement agencies, local and national, to depict African American jazz musicians as deviants, criminals, moral reprobates due their drug use, and the emerging generation of white writers who took to drugs both as a meat to escape a crushing conformity of the Eisenhower 50s and as a way of expressing words that could capsize the old rules and in return truly feel something genuine from the experience. Anslinger is revealed as the unwitting creator of the modern idea of hip, the aesthetic, the pose, the manner of being artists have assumed for decades since, the idea of the artist as outsider, as an outlaw, as an iconoclast. The American avant gard now had a hook to hang its bulky coat on.

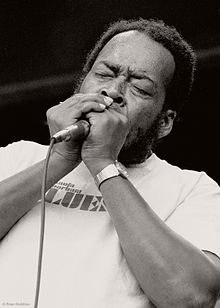

Readers familiar with Beat aesthetics--their emphasis on spontaneity, improvisation, a Zen mindfulness free of distortion and subterfuge --; will be relieved Torgoff goes lightly on the usual apologies made on the Beats behalf. Bop Apocalypse works best at the times when the stories are told of central personalities in the period at crucial moments in their lives. The joy is in the telling details to a chapter to writer Terry Southern (the novels and stories Candy, Blue Movie, Red Dirt Marijuana) and how he discovered pot as a kid, which grew wild on his cousin’s Texas farm, or how saxophonist was introduced to heroin, or Kerouac blitzing himself in clouds of marijuana while he rattled off On the Road in a spurt of superhuman productivity.

Miles Davis, Hubert Huncke, John Coltrane, Mezz Mezzrow, Billie Holliday, William Burroughs, Lester Young and others have their tales told, some details well known and others likely apocryphal, the scenes from their lives revealing a similar scenario, their respective introduction to pot, heroin, amphetamines as a means of coping with their marginalized existence and of forcing their wits and instincts to the edge. There is an idea at work throughout these tales that Torgoff gently insists that there is that drugs. especially marijuana was critical to the helping the writers and musicians in this collection to create their work. He about comes out and insists, at the end of his chapter on Jack Kerouac, and makes the claim that the great many have given to Kerouac’s body of work would have remained unwritten had not taken up the tea habit. He has Kerouac remarking “I need Miss Green to write; can’t whip up interest in anything otherwise.” For myself, who has always found Kerouac’s fiction and poetry problematic at best, a writer who often mistook breathlessness for beauty, Torgoff’s association of being stoned with quality sounds more than a little daydreamy, likening the author’s body of work as that which would be considered to be “…likened to Proust’s, Melville’s and Shakespeare’s.”

This brings to mind something I’d read years ago in a Downbeat Magazine interview with jazz guitar virtuoso Joe Pass, talking about his drug addiction and his eventually getting clean. The interviewer asked if he thought he was actually better and more imaginatively when he was high. Pass gave a cautious answer all the same, to the effect that while he couldn’t say he definitely played better, and he certainly thought he was playing brilliantly while he was high. I kept this in mind reading this otherwise engaging and well-researched book, and remain convinced that the gift to create music or to write poetry are aspects of a personality that exist separate from drug use. That someone can produce chorus after chorus of hard bop jazz ala Parker or compose a monumental poetic masterwork such as Allen Ginsberg’s Howl has more to do with the talent that’s already in place, not because the drugs aided these artists to their particular style of genius. Torgoff does us the favor, though, of presenting the polemic even-handed, although there times when hyperbole gets the best of him.

Raising Kerouac’s literary value to Shakespeare and Proust is an is an example, as is an incident related in a section about Charlie Parker. An intriguing chapter overall, with the sort of telling details of clubs, cities, characters of interest on the risks they took to pursue an art form on the outskirts of what was considered the American mainstream, Torgoff relates the tale of jazz producer and promoter Norman Granz and his organization of a series of concerts billed as “Jazz at the Philharmonic” in Los Angeles in 1946. At this period in brief life, Parker’s behavior was erratic due to the complications of his heroin habit. Parker had barely managed to make it to the West Coast from New York. He quickly fell from sight, looking to score drugs in a city where he had no connections, and arrived late for the concert, which had already started. Torgoff writes:

”…having found what he was looking for, he

showed up twenty eight choruses into ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’ and stepped on the

stage to play a chorus that brought the music to a whole new level and the

audience to its feet, then he stayed on to play alongside Lester Young on ‘Oh

Lady Be Good’…Bird’s choruses astounded musicians and jazz fans everywhere.

Everything he played that night would become part of the basic syntax of jazz…”

This is the kind of overpraise even the most ardent admirer winches at, as curious readers are given soft-shouldered platitudes and proclamations instead of colorful, clear and precise explanations of what the artist is up to, an idea of the tradition a musician is breaking away from and how he’s creating new music based on the traditions he’s learned from. This is a gift jazz critic Stanley Crouch and Gary Giddens, vividly highlighting artistry and contribution over sensationalism, a subtler approach Torgoff does not take on. Worse for Bop Apocalypse is the not-so-subtle idea that the artists that matter,--the artists who break tradition, create new forms, innovators who’s avant gard experiments command respect and influences generations many decades after they’re deceased—have to be chemically deranged in order to have that latent genius become activated and find its fullest and fatal expression. It should be noted that not everyone covered died tragically or fell prey to the foul clutches of permanent addiction—as the biographies of Coltrane, Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong and Ginsberg and Burroughs attest—but Bop Apocalypse provides a constant suggestion that it’s not enough for committed artists to engage their craft to the best of their ability, but that in doing so one must knowingly risk their lives to achieve a genius level of expression the merely sober amongst us cannot. Torgoff’s underlying premise crystallizes much of what is foul with the contemporary notion of romanticism, that the kind of lethal idealization of the drug-related deaths of writers and musicians creates an allure that is seductive and wrongheaded. It is, on the face of it, irrational to consider an early and preventable death of an inspired creator as confirmation of their genius.

Torgoff, though, brings a wealth of research to the subject and, despite the periodic wallowing in cliché and unexamined proclamations, creates an entertaining mosaic through an electric period of American history. What the book lacks insupportable thesis or in establishing how these artists actually to influence each other’s work is made up for by Targoff’s storytelling skills. Imagine this as a film by Robert Altman at his best, a diffuse but alluring tour of the rich details of an aspect of our legacy we must continue to engage. One does wish, though, that the author avoided the unintended irony of writing about artists who changed the way we think about the world with old ideas that merely reinforce our worst habits of mind.