During a dry spell of compelling new authors to read, I ventured a re-acquaintance with Robert Penn Warren's "All The King's Men" and enjoyed nearly as much as when I first came across it during a course while in college. I was familiar with Warren as a poet and critic of the Fugitive Group, and I was never convinced even as an impressionable, nee gullible romantic by his attempts to persuade his readers that what we need is a return to an agrarian economy and all the values and virtues that come with it. This was a return-to-Eden move that will spring up occasionally in the History of literary thought, which seemed less an inspiration to improve life or make lives more authentic through action than it was to dodge the issue about the hard labor of living according to principles based on measurable action; its easier to talk the revolution into being than to hand out a leaflet. As such, I'm too much of a city kid, and even as a whelp thought that

During a dry spell of compelling new authors to read, I ventured a re-acquaintance with Robert Penn Warren's "All The King's Men" and enjoyed nearly as much as when I first came across it during a course while in college. I was familiar with Warren as a poet and critic of the Fugitive Group, and I was never convinced even as an impressionable, nee gullible romantic by his attempts to persuade his readers that what we need is a return to an agrarian economy and all the values and virtues that come with it. This was a return-to-Eden move that will spring up occasionally in the History of literary thought, which seemed less an inspiration to improve life or make lives more authentic through action than it was to dodge the issue about the hard labor of living according to principles based on measurable action; its easier to talk the revolution into being than to hand out a leaflet. As such, I'm too much of a city kid, and even as a whelp thought that Wednesday, February 22, 2017

During a dry spell of compelling new authors to read, I ventured a re-acquaintance with Robert Penn Warren's "All The King's Men" and enjoyed nearly as much as when I first came across it during a course while in college. I was familiar with Warren as a poet and critic of the Fugitive Group, and I was never convinced even as an impressionable, nee gullible romantic by his attempts to persuade his readers that what we need is a return to an agrarian economy and all the values and virtues that come with it. This was a return-to-Eden move that will spring up occasionally in the History of literary thought, which seemed less an inspiration to improve life or make lives more authentic through action than it was to dodge the issue about the hard labor of living according to principles based on measurable action; its easier to talk the revolution into being than to hand out a leaflet. As such, I'm too much of a city kid, and even as a whelp thought that

During a dry spell of compelling new authors to read, I ventured a re-acquaintance with Robert Penn Warren's "All The King's Men" and enjoyed nearly as much as when I first came across it during a course while in college. I was familiar with Warren as a poet and critic of the Fugitive Group, and I was never convinced even as an impressionable, nee gullible romantic by his attempts to persuade his readers that what we need is a return to an agrarian economy and all the values and virtues that come with it. This was a return-to-Eden move that will spring up occasionally in the History of literary thought, which seemed less an inspiration to improve life or make lives more authentic through action than it was to dodge the issue about the hard labor of living according to principles based on measurable action; its easier to talk the revolution into being than to hand out a leaflet. As such, I'm too much of a city kid, and even as a whelp thought that Monday, February 20, 2017

MILO Confronts the Panel | Overtime with Bill Maher (HBO) - YouTube

MILO Confronts the Panel | Overtime with Bill Maher (HBO) - YouTube:

' "Cultural phenomenon" he is, but Milo lacks real gravitas to deal with beyond the initial shock value; beyond a pondering of the contrarian thought bombs he tosses, we realize that he is all but an inch deep and , say, a mere two fee wide for his demonstrated grasp of seminal issues and their underlying causes and proposed cures. Rather quickly, I think, the public will tire of him, conservatives and progressives alike because he'll inevitably be seen as another bright egocentric who espied an opportunity to game the system, the media in this case, to this advantage.Pundits and public will realize that the buzz about him will deal with his celebrity and the manner in which he received the notoriety and not the veracity of his declarations. Will he survive in the media's attention span? Maybe, but likely not as a commentator but rather as a sub species of Professional Celebrity, ranking, perhaps, next to Vanilla Ice and the Leave-Brittany-Alone guy. He might well secure himself a reality show or a low gauge pod cast on YouTube , where he can express his personality to his fullest desire to an dwindling audience who will soon enough become impatient for the next train wreck.Milo is not a stupid man, but for a man who has grown up with the internet, he seems oblivious to the common knowledge that what you say as a celebrity is never forgotten.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Better art through chemistry? Torgoff on Jazz, Beats and Drugs

BOP APOCALYPSE:

Jazz, Race, Drugs, and the Beats

By Martin Torgoff

(Da Capo Press)

Jazz, Race, Drugs, and the Beats

By Martin Torgoff

(Da Capo Press)

|

| (This originally appeared in The San Diego Troubadour. Used with kind permission). |

(

Those expecting a continuous timeline will find this book a bit exasperating, as Torgoff prefers to present his history and his argument in something of a cinematic style, with jump cuts, flashbacks and fast-forwards. There is the sense of him attempting an impressionistic approach to how particular events are linked to creating the mythos we've come to create hip culture. It's a fractured, frustrating but fascinating narrative all the same, dealing with the creation of an outlaw culture with the federal criminalization of Marijuana by the efforts of Harry J. Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics back in the day and the efforts of law enforcement agencies, local and national, to depict African American jazz musicians as deviants, criminals, moral reprobates due their drug use, and the emerging generation of white writers who took to drugs both as a meat to escape a crushing conformity of the Eisenhower 50s and as a way of expressing words that could capsize the old rules and in return truly feel something genuine from the experience. Anslinger is revealed as the unwitting creator of the modern idea of hip, the aesthetic, the pose, the manner of being artists have assumed for decades since, the idea of the artist as outsider, as an outlaw, as an iconoclast. The American avant gard now had a hook to hang its bulky coat on.

Readers familiar with Beat aesthetics--their emphasis on spontaneity, improvisation, a Zen mindfulness free of distortion and subterfuge --; will be relieved Torgoff goes lightly on the usual apologies made on the Beats behalf. Bop Apocalypse works best at the times when the stories are told of central personalities in the period at crucial moments in their lives. The joy is in the telling details to a chapter to writer Terry Southern (the novels and stories Candy, Blue Movie, Red Dirt Marijuana) and how he discovered pot as a kid, which grew wild on his cousin’s Texas farm, or how saxophonist was introduced to heroin, or Kerouac blitzing himself in clouds of marijuana while he rattled off On the Road in a spurt of superhuman productivity.

Miles Davis, Hubert Huncke, John Coltrane, Mezz Mezzrow, Billie Holliday, William Burroughs, Lester Young and others have their tales told, some details well known and others likely apocryphal, the scenes from their lives revealing a similar scenario, their respective introduction to pot, heroin, amphetamines as a means of coping with their marginalized existence and of forcing their wits and instincts to the edge. There is an idea at work throughout these tales that Torgoff gently insists that there is that drugs. especially marijuana was critical to the helping the writers and musicians in this collection to create their work. He about comes out and insists, at the end of his chapter on Jack Kerouac, and makes the claim that the great many have given to Kerouac’s body of work would have remained unwritten had not taken up the tea habit. He has Kerouac remarking “I need Miss Green to write; can’t whip up interest in anything otherwise.” For myself, who has always found Kerouac’s fiction and poetry problematic at best, a writer who often mistook breathlessness for beauty, Torgoff’s association of being stoned with quality sounds more than a little daydreamy, likening the author’s body of work as that which would be considered to be “…likened to Proust’s, Melville’s and Shakespeare’s.”

This brings to mind something I’d read years ago in a Downbeat Magazine interview with jazz guitar virtuoso Joe Pass, talking about his drug addiction and his eventually getting clean. The interviewer asked if he thought he was actually better and more imaginatively when he was high. Pass gave a cautious answer all the same, to the effect that while he couldn’t say he definitely played better, and he certainly thought he was playing brilliantly while he was high. I kept this in mind reading this otherwise engaging and well-researched book, and remain convinced that the gift to create music or to write poetry are aspects of a personality that exist separate from drug use. That someone can produce chorus after chorus of hard bop jazz ala Parker or compose a monumental poetic masterwork such as Allen Ginsberg’s Howl has more to do with the talent that’s already in place, not because the drugs aided these artists to their particular style of genius. Torgoff does us the favor, though, of presenting the polemic even-handed, although there times when hyperbole gets the best of him.

Raising Kerouac’s literary value to Shakespeare and Proust is an is an example, as is an incident related in a section about Charlie Parker. An intriguing chapter overall, with the sort of telling details of clubs, cities, characters of interest on the risks they took to pursue an art form on the outskirts of what was considered the American mainstream, Torgoff relates the tale of jazz producer and promoter Norman Granz and his organization of a series of concerts billed as “Jazz at the Philharmonic” in Los Angeles in 1946. At this period in brief life, Parker’s behavior was erratic due to the complications of his heroin habit. Parker had barely managed to make it to the West Coast from New York. He quickly fell from sight, looking to score drugs in a city where he had no connections, and arrived late for the concert, which had already started. Torgoff writes:

”…having found what he was looking for, he showed up twenty eight choruses into ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’ and stepped on the stage to play a chorus that brought the music to a whole new level and the audience to its feet, then he stayed on to play alongside Lester Young on ‘Oh Lady Be Good’…Bird’s choruses astounded musicians and jazz fans everywhere. Everything he played that night would become part of the basic syntax of jazz…”

This is the kind of overpraise even the most ardent admirer winches at, as curious readers are given soft-shouldered platitudes and proclamations instead of colorful, clear and precise explanations of what the artist is up to, an idea of the tradition a musician is breaking away from and how he’s creating new music based on the traditions he’s learned from. This is a gift jazz critic Stanley Crouch and Gary Giddens, vividly highlighting artistry and contribution over sensationalism, a subtler approach Torgoff does not take on. Worse for Bop Apocalypse is the not-so-subtle idea that the artists that matter,--the artists who break tradition, create new forms, innovators who’s avant gard experiments command respect and influences generations many decades after they’re deceased—have to be chemically deranged in order to have that latent genius become activated and find its fullest and fatal expression. It should be noted that not everyone covered died tragically or fell prey to the foul clutches of permanent addiction—as the biographies of Coltrane, Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong and Ginsberg and Burroughs attest—but Bop Apocalypse provides a constant suggestion that it’s not enough for committed artists to engage their craft to the best of their ability, but that in doing so one must knowingly risk their lives to achieve a genius level of expression the merely sober amongst us cannot. Torgoff’s underlying premise crystallizes much of what is foul with the contemporary notion of romanticism, that the kind of lethal idealization of the drug-related deaths of writers and musicians creates an allure that is seductive and wrongheaded. It is, on the face of it, irrational to consider an early and preventable death of an inspired creator as confirmation of their genius.

Torgoff, though, brings a wealth of research to the subject and, despite the periodic wallowing in cliché and unexamined proclamations, creates an entertaining mosaic through an electric period of American history. What the book lacks insupportable thesis or in establishing how these artists actually to influence each other’s work is made up for by Targoff’s storytelling skills. Imagine this as a film by Robert Altman at his best, a diffuse but alluring tour of the rich details of an aspect of our legacy we must continue to engage. One does wish, though, that the author avoided the unintended irony of writing about artists who changed the way we think about the world with old ideas that merely reinforce our worst habits of mind.

Saturday, February 4, 2017

Bromancing at the Ramparts

|

| BUCKLEY and MAILER: The Difficult Frienship that Shaped the SixtiesBy Kevin M. Schultz |

Both men in the title were large presences in the worlds they inhabited, and likewise enjoyed the continued company of other men of equally over sized personality. Schultz gives an accurate , vivid and swift accounting of the relationship between Mailer and Buckley, summing up their world views , their similarities and differences handsomely, but there is not much here in the way of literary criticism or speculation.

Schultz's thesis, that both writers represented conflicting movements in the culture, the stalwart Right battling off the revolutionary Left, is a shaky at best.Buckley, though, was the leader of a movement, the Conservative Movement, which he was instrumental in founding and organizing with his publication The National Review and his program Firing Line. He used the NR platform to formalize a philosophy that charged thousands of younger conservatives into getting involved in politics, their greatest triumph being the election of Ronald Reagan.Mailer did co-found the Village Voice, of course, but sold his stake in it to finance his films, and was, unlike Buckley, a political wild card. He sided with the left on many a cause and belief, but there was a stubborn conservative contrarianism in is viewpoint, a quality that made him fascinating as a writer and thinker but, shall we say, unstable as an ally, let alone leader of anything.His treatment of both writers is, I think, much too worshipful . This is precisely the kind of subject that makes you wish the late John Leonard were still with us in order to take apart , inspect and comment upon the public utterances and behaviors of Bill and Norm and render a judgement as to how both men, as thinkers, will be effected by the eventual and brutal judgement of history. But for those fascinated by the culture, art and politics of the 50s and 60s, certainly a combustible era for America, Buckley and Mailer is an informative, if terse, recounting of the doings of two of its most interesting white men.

Schultz's thesis, that both writers represented conflicting movements in the culture, the stalwart Right battling off the revolutionary Left, is a shaky at best.Buckley, though, was the leader of a movement, the Conservative Movement, which he was instrumental in founding and organizing with his publication The National Review and his program Firing Line. He used the NR platform to formalize a philosophy that charged thousands of younger conservatives into getting involved in politics, their greatest triumph being the election of Ronald Reagan.Mailer did co-found the Village Voice, of course, but sold his stake in it to finance his films, and was, unlike Buckley, a political wild card. He sided with the left on many a cause and belief, but there was a stubborn conservative contrarianism in is viewpoint, a quality that made him fascinating as a writer and thinker but, shall we say, unstable as an ally, let alone leader of anything.His treatment of both writers is, I think, much too worshipful . This is precisely the kind of subject that makes you wish the late John Leonard were still with us in order to take apart , inspect and comment upon the public utterances and behaviors of Bill and Norm and render a judgement as to how both men, as thinkers, will be effected by the eventual and brutal judgement of history. But for those fascinated by the culture, art and politics of the 50s and 60s, certainly a combustible era for America, Buckley and Mailer is an informative, if terse, recounting of the doings of two of its most interesting white men.

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

Sunday, January 22, 2017

The Conway Con

So is this how it's going to be ? First the White House Spokesman Sean Spicer glaringly misrepresents the numbers of the Inauguration attendance by saying the crowds were the "biggest ever". Now Trump's chief apologist Conway announces that the Spokesman gave "alternative facts" about the numbers instead of simply saying that Spicer was mistaken, or more simply, was wrong. That would have given this faux pas a fast, if embarrassing, arrest, but it creates more concern and justification for more scrutiny on these rascals.

"Alternative facts"? This phrase pretty much reflects the magical and impulsive thinking of Trump's campaign rhetoric, where the first thing that came into his head at a speech was the next thing he said, without vetted proof of any sort, surreally incoherent declarations he would double, triple and quadruple down on when pressed as to their accuracy. There are, of course, no such things as "alternative facts". There are facts that are not accounted for, matters not yet discovered, recorded and verified, but all the same, there are no "alternative facts". There are facts known and facts unknown, and if there are facts that demonstrably disprove that what previously thought was true, you change your assumption, you change your theory of how the world works.

You begin to think that Trump's hallucinatory grasp of things is contagious among those who've been in close quarters to him for too long. Might this be a case of Elvis Syndrome, or Michael Jackson for that matter, where rich and deluded men are surrounded not by friends or concerned family but rather by hired henchmen who's job it is to reinforce the leader's slanted cosmology? It would a good time for us to re-read George Orwell's brilliant essay "Politics and the English Language", a trenchant piece that exposes how propagandist on the Left and the Right usurp common place words, phrases and concepts and find ways of using the language to advance their ideological goals.My worry about Conway's use of the phrase "alternative facts" comes that her use seemed reflexive, not performative. She sounded as if the distinction made any difference. You wonder if she knew the difference at all.

Meaning and murk in modern poems

Experimental poetry used to be the kind of stuff that broke with established forms of verse writing, both in form and aesthetic. A good survey course in Western Poetry will pretty much be the history of one school of poetry arising in response and/or rebellion against forms that had long been dominant, with the more daring and expansive poetry influencing younger poets to the degree that the experimenters over time become the old guard. This goes on and on, exceptions to rules becoming rules until another generator of impatient experimenters come along with their contrarian notions of what verse should be, usurping fusty older poets and becoming the dominant ones themselves, fat, complacent and ripe for overturning. I don’t know if that’s a working dialectic, but it is something that has continued since literate men and women sought to express grand and vague inspirations in language that did more than merely describe or paraphrase existence. It’s my feeling that experimentation has become the norm and that we have these days are recycling of previous avant gard ideas and gestures, names if theories and practices changed ever so much.

But not so much. It's gotten to the point that the school of poets who are referred to as the New Formalist, poets who’ve tired of free verse and variable feet and the several generations of “open forms” in poetry and compose poems that rhyme and which employ traditional meter, have become a controversial matter in that they threaten to usurp the hegemony of the experimental tradition.

To each their own as to what they prefer to put in front of their eyes, and to each their own for developing a critical rationale for their what sorts of peculiar phrase deformations give them pause to stroke their chin, scratch their head and laugh or cry as the case may be. Emotional responses reconstituted and subjected to the marginalia that makes even recipes for stone soup resemble nothing less than unappetizing exercises in gratuitous brain power is, to an extent, another sort of poetry. It's a condition that admits, tacitly, that we're unable to get to the actual heart of our states of being, fluid as they are, but we are capable of conducting our recollections through a lexicon that most closely resembles whatever idealized paradigm momentarily fits the fleet-footed of a perception. It's guesswork of a kind, never on the money, never finalizing the dissension among the talkers who wait their turn to speak their world into existence, but still, something that brings a quality we cannot live without. A love of process, of trying to come up with means, methods, and ideas of using language that is as fluid and predictable as the experience itself.

Myself, I am attracted to any kind of poetic writing that has that rare quality of being dually fresh and unique; I am less intrigued by the theory behind a poem, experimental or traditional than I am on it reads, on whether it works. If it produces a reader’s satisfaction, then it becomes useful to investigate what a writer has done as an artist in this odd medium, bringing skill and on the fly inspiration to bear in the writing. This can be the case with Ron Silliman, John Ashbery, two poets who are arrested my attention with their creation of indirect address of the living expression, and it is the case for Thomas Lux and Dorianne Laux, two other poets who are not averse to letting in you follow their line of thinking and who still lead you results that are unexpected and extraordinary.

Sunday, January 15, 2017

Spider's out to get ya

I pretty much thought the 70s Midnight Special program on NBC was as cheesy as most of the pop rock they presented from that musically sorry decade, but they did raise their game once to glorious heights by presenting a mini-concert of David Bowie and band, in full glam regalia, on their show. Recorded at the legendary Marquee Club in London's Soho, it is Bowie at his most compelling and bracing. The first song in particular , 1984, is especially notable, a lean, stripped-down hard rock version that has all the things Bowie's tunes have for us, nicely turned changes, suddenly menacing riffs, a combination of industrial grind, gay disco and hard rock brutalism. The drummer was Aynsley Dunbar, who plays like man determined to make that kit he has is never played again; hard, furious, fast, he has the power of Keith Moon and the efficient virtuosity with the tricky time signature. Bowie, of course, is odd, compelling, still something to look at all these decades later, a presence with talent to match his audaciousness.

"LIVE BY NIGHT" : Affleck is not the auteur he thinks he is

Ben

Affleck rebuilt his reputation mostly on the strength of his skills as an able

and savvy director, having directed the successful and justifiably praised

films “Gone Baby Gone”, “The Town”

and ‘Argo”, for which he won the Oscar for Best Director. Affleck

is a marginally good actor, good when the scripts and casting are on the money — think of how wonderful John

Wayne was in “ Red

River” and how awful he was as Genghis Khan in “The Conqueror” — and his

evolution , during his time off camera, into learning the craft of film

direction (and the obligations of being a producer) seems to have given a sharp

and canny sense of what kind of material he can be credible in as an actor and

director. He’s been doing good work in films he hasn’t directed but starred in,

such as “Gone Girl”, “The Accountant” and

“Batman v Superman”; he has gotten praise from critic and fan both for his

sharpened sense of the camera lens. As with Wayne and fellow actor-director

Clint Eastwood, Affleck has learned to do fine work within his limited range as

an actor.

But

the 4th time is the charm, the warning, seen in his new period crime drama “Live by Night”,where

we come across him as a petty criminal in 30s era Boston, finding himself

caught between a war between the Irish and the Italian gangs that are vying for

domination. Long story brutally abbreviated, our hero finds himself working for

the Italians as he heads up their Miami rum running operation. What unfolds

after that is a string of gangster movie cliches and hackneyed melodramatic

plot turns that cannot fool you into thinking that what’s happening between the

characters on screen — whether the premise is love, lust, betrayal, revenge or philosophical convictions that become

endlessly compromised by real life complications — is

anything more than mere mechanics. The story is a machine running on the fuel

of over familiar parts. The script, based on a novel by the

estimable Dennis Lehanne, is credited to Affleck alone , and this where

the blame for the film’s listless wade through lifeless plot turns must fall;

he displays a tin ear for fresh dialogue and is unable, in this effort, to

create anticipation, a sense that a viewer does not how any of this will end.

Affleck’s writing and direction hasn’t the

patience nor grace to make this work. Glaring as well is Affleck’s casting in

the lead role. Affleck is too tall, too squared jawed, too muscular; he looks

uncomfortable in the suits he’s put himself; worse, often times he appears

about to burst out of them, Hulk style.And again, about Affleck’s acting limits

come into play, which is to say that his facial expressions are not subtle nor

do they lure you in to read the lines of his face or the shine or lack thereof

in the eyes; Affleck seems to have fixed expressions for happy, sad, angry,

raging, laughing, crying, mostly robotic and seeming unmotivated by the tragedies, murders and raging extremes happening around him. Much as I've defended Affleck in the past as an actor, this time he seems aware of only where he he is in relation to the camera.

It’s worth noting that the praise for writing on Affleck’s other efforts as director — “Gone Baby Gone”, The Town” and “Argo” — were for efforts where there were collaborators in the scripting, in the persons of Chris Terrio, Aaron Stockard and Peter Craig. The implication seems clear, that what the author scribes provided were a sensibilities that could carve Affleck’s contributions to the respective project’s line and and theme into something sharper, less obvious. The dispiriting stream of over used tropes in ‘Live by Night” is such that it blunts the efforts a fine cast , Zoe Saldana and Chris Cooper in particular. This is cool professionalism from actors trying to eke out small moments of good craft from a script that gives them no love.

It’s worth noting that the praise for writing on Affleck’s other efforts as director — “Gone Baby Gone”, The Town” and “Argo” — were for efforts where there were collaborators in the scripting, in the persons of Chris Terrio, Aaron Stockard and Peter Craig. The implication seems clear, that what the author scribes provided were a sensibilities that could carve Affleck’s contributions to the respective project’s line and and theme into something sharper, less obvious. The dispiriting stream of over used tropes in ‘Live by Night” is such that it blunts the efforts a fine cast , Zoe Saldana and Chris Cooper in particular. This is cool professionalism from actors trying to eke out small moments of good craft from a script that gives them no love.

Friday, January 13, 2017

Your sponsor is not a trained professional

I dislike the self-help phrase "Feelings are not

facts." The people who say have smiles that are so tight that it makes you

think those rigid smirks are the result of a string of psychotic breakdowns;no

one who utters the convenient adage truly seems convinced that it’s of any real

use to someone who’s losing their emotional equilibrium. One has to do a bit of

interpretation to get a sense of what the author was trying to say. I refute

this cliché thusly: if I am sad, elated, angry, in love or grieving, it is a

FACT that I'm feeling that way. The knee jerk bootstrappism of the cliché, on

the face of it, discounts feelings and implies you ought to ignore them. Bad

advice, dangerous advice. If you're feelings are out of hand and seeming too

much to handle, one is advised STRONGLY to get help to understand the feelings

and what one can do to recover. Feelings are not facts" is intended to tell sufferers

that one should not let their feelings overwhelm them and prevent them from

being proactive in their life. That I am feeling depressed, bereaved, elated,

et al, however, are, in themselves, facts, and

excessive states of each or in combination thereof that prevents the sufferer

from engaging their daily life fully cannot be dismissed with this smug phrase.

There are reasons one continues to be overwhelmed by fear, grief, anxiety,

angst, a feeling of impending doom; if ignored, these feelings can become truly

immobilizing. The danger in this is that the phrase seems to have

morphed from being a part of a psychiatric / therapeutic treatment modality

where distinctions are explicit and the aim, guided with professional aid, is

to repair and reinforce a patient's coping skills, to make them increasingly resilient in spite of their

feelings. The phrase implies a short cut and, sadly, I see many who would

otherwise benefit from a more therapeutic situation vying for a faster fix.

Generally speaking, they don't appear to be making progress. I see a lot of

this and, in fact, have my own issues to wrestle with as a sober alcoholic. There

is an AA phrase, an unfortunate one I think, that states that alcohol is merely

a symptom of an underlying disorder. I know precisely what the author of that

phrase meant, that there are reasons why we drank, emotional distresses and

such that are now triggers toward the temporary and potentially terminal relief

booze supplies, but it is said so often by members without thought that it

implies strongly that if one attends and corrects the causes of the symptoms,

one may return to normal drinking. It undercuts the importance of remaining

abstinent. Alcohol, in my experience, was not a symptom, it was (capital was)

and remains (capital remains) the problem itself. Generally speaking, all the

other things that AA offers effective help in--making amends, righting wrongs,

developing a workable spirituality that allows one become a better person, a

sober person--are impossible to achieve unless one adheres to permanent

physical sobriety. I just don't appreciate complicated problems being

trivialized by way of bumper sticker slogans.

I dislike the self-help phrase "Feelings are not

facts." The people who say have smiles that are so tight that it makes you

think those rigid smirks are the result of a string of psychotic breakdowns;no

one who utters the convenient adage truly seems convinced that it’s of any real

use to someone who’s losing their emotional equilibrium. One has to do a bit of

interpretation to get a sense of what the author was trying to say. I refute

this cliché thusly: if I am sad, elated, angry, in love or grieving, it is a

FACT that I'm feeling that way. The knee jerk bootstrappism of the cliché, on

the face of it, discounts feelings and implies you ought to ignore them. Bad

advice, dangerous advice. If you're feelings are out of hand and seeming too

much to handle, one is advised STRONGLY to get help to understand the feelings

and what one can do to recover. Feelings are not facts" is intended to tell sufferers

that one should not let their feelings overwhelm them and prevent them from

being proactive in their life. That I am feeling depressed, bereaved, elated,

et al, however, are, in themselves, facts, and

excessive states of each or in combination thereof that prevents the sufferer

from engaging their daily life fully cannot be dismissed with this smug phrase.

There are reasons one continues to be overwhelmed by fear, grief, anxiety,

angst, a feeling of impending doom; if ignored, these feelings can become truly

immobilizing. The danger in this is that the phrase seems to have

morphed from being a part of a psychiatric / therapeutic treatment modality

where distinctions are explicit and the aim, guided with professional aid, is

to repair and reinforce a patient's coping skills, to make them increasingly resilient in spite of their

feelings. The phrase implies a short cut and, sadly, I see many who would

otherwise benefit from a more therapeutic situation vying for a faster fix.

Generally speaking, they don't appear to be making progress. I see a lot of

this and, in fact, have my own issues to wrestle with as a sober alcoholic. There

is an AA phrase, an unfortunate one I think, that states that alcohol is merely

a symptom of an underlying disorder. I know precisely what the author of that

phrase meant, that there are reasons why we drank, emotional distresses and

such that are now triggers toward the temporary and potentially terminal relief

booze supplies, but it is said so often by members without thought that it

implies strongly that if one attends and corrects the causes of the symptoms,

one may return to normal drinking. It undercuts the importance of remaining

abstinent. Alcohol, in my experience, was not a symptom, it was (capital was)

and remains (capital remains) the problem itself. Generally speaking, all the

other things that AA offers effective help in--making amends, righting wrongs,

developing a workable spirituality that allows one become a better person, a

sober person--are impossible to achieve unless one adheres to permanent

physical sobriety. I just don't appreciate complicated problems being

trivialized by way of bumper sticker slogans.Sunday, January 8, 2017

More old record reviews

Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) - Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band (Warner Brothers) This is one of the few times tha t all of Beefheart's freaky talents have been . captured successfully on record, easily the first time since 1968's Trout Mask Replica. The music is as crankishly idiosyncratic as it's ever been (jump-cut time signatures, a free mixing of "free-jazz" randomness and pop song structures, blues and neoclassical shades blending into thick atonal texture) and Beefheart's vocals, one of the raspiest voices anywhere, de liver his dadaesque, free-associative lyrics with the same kind of off-kilter verve.(One would be remiss in thinking that Beefheart's lyrics are without substance or lack meaning: no less than Wallace Stevens, who explored his dreams of a world of perfect arrangements and their contradictions, Beefheart, nee Don Van Vliet chooses to inspect a terrain of imperfect things, material and organic, and forge connections and conversation between them with nothing but the force of applied and intense whimsy. )

The effect sounds like an Unlikely super session between Howlin' Wolf and Alfred Jarry (costumes designed by Max Ernst) . His new Magic Band, featuring ex-Zappa sidemen as Bruce Fowler (trombone) and Art Tripp (drums) , handle the demands of the music with disciplined ease, executing Beefheart 's quixotic time signatures and self-deconstructing arrangements with a professionalism that tends toward both perfection and liveliness, usually an unlikely symbiosis in art-rock groups. However cerebral Beefheart's music sounds, though, it should be POinted out that Shiny Beast is a fun album, full of good humor and strong material. This time out, The Captain is out to entertain and beguile, a work of art that does what any object of scrutiny must do, which is to offer a genius's blend that confuses, edifies, confounds and elevates the individual attendee .

The effect sounds like an Unlikely super session between Howlin' Wolf and Alfred Jarry (costumes designed by Max Ernst) . His new Magic Band, featuring ex-Zappa sidemen as Bruce Fowler (trombone) and Art Tripp (drums) , handle the demands of the music with disciplined ease, executing Beefheart 's quixotic time signatures and self-deconstructing arrangements with a professionalism that tends toward both perfection and liveliness, usually an unlikely symbiosis in art-rock groups. However cerebral Beefheart's music sounds, though, it should be POinted out that Shiny Beast is a fun album, full of good humor and strong material. This time out, The Captain is out to entertain and beguile, a work of art that does what any object of scrutiny must do, which is to offer a genius's blend that confuses, edifies, confounds and elevates the individual attendee .

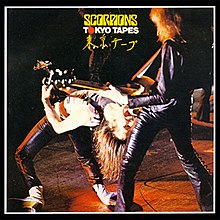

Tokyo Tapes - Scorpions (RCA) Recorded live in Japan (the new hard-rock capital of the world), the German Scorpions play their way through four sides of machine-shop heavy metal. The songs are generally undistinguished (this band exhibits little originality in the songwriting department) , the drum work tends to be as rigid as rigor mortis, and the singing, in phonetic English, approximates the sound of a barking dog_ What makes the album a delight, though, is the guitar work of Ulrich Roth. Like Edward Van Halen, Roth's style combines flash (ala Jeff Beck and Johnny Winter), technique (Allan Hold s worth and Harvey Mandel), power (Leslie West a and Hendrix) and taste (Ritchie Blackmore). His solos are swooping, over-powering sorties, with dizzying sonic riffs, fleet-fingered note configurations and screaming obstinate sustains. This leads to a monotonous virtuosity that begs to be paid attention to, though. As is the case with most fret masters in rock and roll, the harmonic palette is limited compared to the full chromatic smorgasbord classical or jazz formats afford musicians given to playing many notes; after a bit , all those scurrying steeple races up and down the guitar neck resemble inspiration and melodrama less and the mechanical fury of factory machines more. Maybe that’s the point.

Tokyo Tapes - Scorpions (RCA) Recorded live in Japan (the new hard-rock capital of the world), the German Scorpions play their way through four sides of machine-shop heavy metal. The songs are generally undistinguished (this band exhibits little originality in the songwriting department) , the drum work tends to be as rigid as rigor mortis, and the singing, in phonetic English, approximates the sound of a barking dog_ What makes the album a delight, though, is the guitar work of Ulrich Roth. Like Edward Van Halen, Roth's style combines flash (ala Jeff Beck and Johnny Winter), technique (Allan Hold s worth and Harvey Mandel), power (Leslie West a and Hendrix) and taste (Ritchie Blackmore). His solos are swooping, over-powering sorties, with dizzying sonic riffs, fleet-fingered note configurations and screaming obstinate sustains. This leads to a monotonous virtuosity that begs to be paid attention to, though. As is the case with most fret masters in rock and roll, the harmonic palette is limited compared to the full chromatic smorgasbord classical or jazz formats afford musicians given to playing many notes; after a bit , all those scurrying steeple races up and down the guitar neck resemble inspiration and melodrama less and the mechanical fury of factory machines more. Maybe that’s the point.Thursday, January 5, 2017

BEST RECORDS OF 1980

(from the UCSD Guardian, where I was bloviating for a few years as Arts Editor during the late Seventies, early Eighties.-tb)

After a modicum of meditation, soul-searching, and late-night phone calls, I've decided that this annual autopsy we call a "year-in-review" won't be as grisly as I imagined. In fact, the most outlandish generalization one could make about the state of pop music in 1979 is that it was merely "okay." As in any year, there were plenty of decent albums that passed through my hands on to mine and my writer's turntable, but there was a sizable proportion of discs from new and established artists that fall well below what one wants to hear. In any case, rock and roll don't seem to be dying at the present moment, though I, like anyone else who's been involved with the stuff too much for their own good, would have to have heard more records that reached the high watermark. What follows are my annual hit-and-run comments on the previous year's more or less notable releases.

1) Armed Forces — Elvis Costello (Columbia): Although Nick Lowe's production is at times heavy-handed and strains too often for effect (too much piano, echo chambers, an overkill of vocal over dubs), Costello remains a formidable talent that no amount of cheap garnish can obscure. At best, (more times than not) Costello is dead on target. At worst, he's utterly incoherent and artlessly paranoid.

2) Nice Guys — The Art Ensemble of Chicago (ECM): By definition, avant-garde or "free" jazz is supposed to be difficult for the uninitiated to warm up to, but the Ensemble's latest seems (to me at least) to be the one '79 release in the genre that even Mangione fans can find enjoyable. Nice Guys is a brilliant crazy quilt of styles and strategies, with the shifting textures and colorations of saxophones, trumpets, drums, bass, and a plethora of more obscure instruments proceeding through a fascinating session of unconventional improvisation.

3) Trevor Rabin — Trevor Rabin (Chrysalis) Rabin is a singer-songwriter-guitarist from South Africa who's same-named debut album supplies the kind of mega-rock that Todd Rundgren's been promising for years. Rabin proceeds through a far-fetched array of styles, from Mountainesque heavy-metal, syrupy ballads, McLaughlin-inspired jazz-rock, Zappa-like ensemble virtuosity, through disco and reggae, often blending these incongruous strands into the same song. And, incredibly, it works.

4) Van Halen II — Van Halen (Warner Brothers): Edward Van Halen plays flashy hard rock guitar with admirable vengeance and ingenuity; that is enough for me.

5) One of a Kind — Bill Bruford (Polydor): The former Yes, King Crimson and Genesis drummer deftly leads a band of superb musicians through a session that combines the best of progressive rock (compositional organization with a rich sense of harmony and counterpoint) and the best of fusion rock (inventive soloing meshing hard-rock dynamics with fleet-fingered technique). Guitarist Allan Holdsworth performs as though in a state of grace, and bassist Jeff Berlin is someone to watch out for.

6) New Values — Iggy Pop: Iggy, who is the godfather of punk if anyone is, has finally transcended the problems that've too often stopped him from delivering that all-purpose knockout punch. The music is crunchy, cantankerous rock and roll, Iggy's vocals have the appeal of the off-hand remark, and the lyrics succeed in being anti-intellectual without the obnoxious posturing that is the calling card of many whom Iggy has influenced. Iggy proves here that he is the main-man.

7) Shiny Beast (Bat Pull Chain) — Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band

ner Brothers): Beefheart, rock's most idiosyncratic avant-garde individualist, is refreshingly in place for once, seeming to have hammered his worrisome kinks and quirks into a form that benefits his talent for constructing fractured, asymmetrical, dada-derived music. Splendid use of free jazz tonalities, urban blues, Caribbean rhythms, and rhythm and blues. (Warner Brothers): Beefheart, rock's most idiosyncratic avant-garde individualist, is refreshingly in place for once, seeming to have hammered his worrisome kinks and quirks into a form that benefits his talent for constructing fractured, asymmetrical, dada-derived music. Splendid use of free jazz tonalities, urban blues, Caribbean rhythms, and rhythm and blues.

8) Fear of Music — Talking Heads (Sire): Talking Heads, I fear, is more of an alliance with art-rockers like Eno, Roxy Music and John Cale than with the New Wave, but that hasn't stopped me from liking them. Their music has a cleverly controlled graininess that puts them half-way between garage band amateurism and the post-twelve tone rigors of the "new music" conceptualists. David Byrne's lyrics, sung in a voice that sounds as though it might evaporate at any moment, expresses the tortured holistics of the paranoid mind while allowing as little self-pity as possible. This is the work of a refreshingly straightforward sociopath.

9) Rust Never Sleeps — Neil Young (Warner Brothers): Young, who, like Norman Mailer, has been producing advertisements for himself for years to little advantage (self-revelation must attain the universal, not the therapeutic, it's to sit well as something I'd like to investigate), has released a masterpiece of a kind, a rock and roll testament that deals with American icons, institutionalized violence, and the sand-trap of self-love (among other themes). And Crazy Horse helps Young play some of the dirtiest rock and roll of the sear.

10) Squeezing Out Sparks — Graham Parker: Parker bites the head off of everyone who's ever done him dirt with music and lyrics that have the mainstream kick of the old Rolling Stones. Blunt, uncompromising stuff.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-

here