Saturday, January 30, 2010

Thursday, January 28, 2010

J.D.SALINGER IS DEAD

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Michelangelo's complaint

above me all the time, dribbles paint

so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!

Michelangelo was a sculptor and a poet, and Robert Pinsky has posted a poem of his regarding the aches and pains he experienced as he undertook the challenge of painting the Sistine Chapel.The sonnet is less interesting as poetry than it is a document of how Michelangelo felt about his labor over the commission he didn't want, the pa

inting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. No offense to Gail Mazur's translations, but the fleshy descriptions that inform us of what appendages and what internal organs ache likely read better in the Master's original Italian, the advantage of the original tongue being that one could better ear the innate musicality of the nouns and their near rhymes. This seems just a tad strained, and reads as though Mazur had to create phrases of her own when some word clusters couldn't be clearly conveyed into English. This raises the question as to how much of Michelangelo we were actually reading. Or perhaps I'm just tone deaf to the whole matter. What do believe, though, is that we are getting an accurate reading of the great artist's pains and frustrations; what is flat as poetry is fascinating as document. This is a another cranky, self-lampooning poem from a genius who finds that possessing over-sized talent can be a large cross to bear, being, in this case, a great physical pain. I did enjoy the way in which Michelangelo described the way his body has been twisted and reconfigured in the pursuit of filling up an unlikely surface ; the canvas, as it were, and the artist's body , were in the least likely of locations. The poem is the venting of a man who angry with the moral and social authority of the Pope who is preventing him from working in what he feels is his true medium, sculpture; painting is a curse that visits a stream of punishments upon. It's as if an interloper is being punished :

inting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. No offense to Gail Mazur's translations, but the fleshy descriptions that inform us of what appendages and what internal organs ache likely read better in the Master's original Italian, the advantage of the original tongue being that one could better ear the innate musicality of the nouns and their near rhymes. This seems just a tad strained, and reads as though Mazur had to create phrases of her own when some word clusters couldn't be clearly conveyed into English. This raises the question as to how much of Michelangelo we were actually reading. Or perhaps I'm just tone deaf to the whole matter. What do believe, though, is that we are getting an accurate reading of the great artist's pains and frustrations; what is flat as poetry is fascinating as document. This is a another cranky, self-lampooning poem from a genius who finds that possessing over-sized talent can be a large cross to bear, being, in this case, a great physical pain. I did enjoy the way in which Michelangelo described the way his body has been twisted and reconfigured in the pursuit of filling up an unlikely surface ; the canvas, as it were, and the artist's body , were in the least likely of locations. The poem is the venting of a man who angry with the moral and social authority of the Pope who is preventing him from working in what he feels is his true medium, sculpture; painting is a curse that visits a stream of punishments upon. It's as if an interloper is being punished :My haunches are grinding into my guts,

my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight,

every gesture I make is blind and aimless.

My skin hangs loose below me, my spine's

all knotted from folding over itself.

I'm bent taut as a Syrian bow.

There's not the remotest suggestion of joy in this passage. Rather than being in the moment with the object he's fashioning, gather inspiration as he goes along and reaching a point where mere technical mastery comes to the service of actual genius, what is described here is someone trying to remember formalities of something he wasn't comfortable doing, guessing around the edges of the tableau as to where colors and their textures out to go. He is "blind and aimless" , unable to see the work in whole, unable to envision it as finished, save for scaled down drawings outlining the work in progress. Interestingly, this isn't the voice of the supremely confident artist we read about, but rather the self-denigrating venting of a trainee in a new job. The feeling of doing this job wrong comes across as a palpable fatalism.The poem that surpasses mere complaint, it reveals the acute pain that accompanies the unwanted commission. But for all the discomfort and twisting and bending and otherwise unnatural distensions and compressions his body must absorb during the work, a clenched teeth determination comes across; as much as I feel pain and degradation, as great as this ceiling will be. We've come to admire the spectacle of the ceiling, the detail, the ingenious solutions to problems that arose, but for the artist it seems merely something to be endured, gotten over with. The ceiling appeared masterful as if composed from a resentment; Michelangelo sounds as if he regards this as mere professionalism.

My painting is dead.

Defend it for me, Giovanni, protect my honor.

I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.The sculptor feels abused, made to perform an unnatural function for a client whom he couldn't refuse. His body and his art were prostituted in the service of another man's egomania, and so he calls for his honor to be defended. He is not a painter, he assures us, and the irony of it all is that it is the painting on the Sistine Chapel for which he best known. Likely he would've loathed the recognition and seethe mightily that the masses who adore the painting are fools and simpletons.He was not a painter. Frank O'Hara wasn't a painter either. But he was an excellent poet.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

The Faith of Graffiti: a brief exchange

ng Norman Mailer's "The Faith of Graffiti" , and it seems astounding Mailer grasped a street aesthetic born of marginalized , nonwhite urban youth. This is an important essay I suspect Eric Michael Dyson or Cornell West would come to admire. Mailer is susceptible to the charges of depicting these artists as noble savages, but he does make the connections between the impulse to transform the environment by adding a bit of one's personality upon it with the shattered reconstructions of Picasso's vision. Nice polemic, this. What impresses me is that he refined the existential-criminal-at-the-margins tact he controversially asserted in his essay "The White Negro", backing away from the idea that violence could direct one to knew kinds of perception and knowledge, and emphasized an aesthetic response to a crushing , systematized oppression. Living long enough ,I suppose, made Mailer aware of strong trend in urban style that added value to circumstances and individual growth that didn't involve a fist, a gun or a knife.

ng Norman Mailer's "The Faith of Graffiti" , and it seems astounding Mailer grasped a street aesthetic born of marginalized , nonwhite urban youth. This is an important essay I suspect Eric Michael Dyson or Cornell West would come to admire. Mailer is susceptible to the charges of depicting these artists as noble savages, but he does make the connections between the impulse to transform the environment by adding a bit of one's personality upon it with the shattered reconstructions of Picasso's vision. Nice polemic, this. What impresses me is that he refined the existential-criminal-at-the-margins tact he controversially asserted in his essay "The White Negro", backing away from the idea that violence could direct one to knew kinds of perception and knowledge, and emphasized an aesthetic response to a crushing , systematized oppression. Living long enough ,I suppose, made Mailer aware of strong trend in urban style that added value to circumstances and individual growth that didn't involve a fist, a gun or a knife.-----------------

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Terry Gilliam Gets it Right

I equate clutter with flash, and it's the case that Gilliam really does not allow us much time in his films to allow his designs to register or resonate. It's the kind of flash one means when they discuss carnival game decoration--lots of cheap prizes dressing up a joint (I am an ex-carnie, after all) meant to attract attention, not intelligence. I... See More often wished there was less ebullience and more discretion in his designs; his best visual ideas goto waste. In "Imaginarium", they do not, as the tragedy with Ledger forced Gilliam to limit his range and so lend his story a logic that made sense in the terms of the fantasy he was operating within; he paid attention to his idea and didn't overshoot it.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Last Resort

No one

is poor. Like lions caged too long, the waves

loll lazily along the beach. He stares

out at the bright horizon, lost in thought.

I wonder if his memories might hurt.

Tonight, beneath a moon as clear and plain

as need, we'll drink banana daiquiris.

He'll ask the mariachi band to play

a Cuban song, which they'll almost get right.

But in the morning, he must realize,

we'll still awaken here. Same sun, same sea:

the simulation, if more dream than real,

is close enough...

The son wonders what his father is thinking about and wonders if the quiet state is either a profound contemplation of things , or the consequence of lack of thought. Campo doesn't belabor the point or lard up this lyric with a routine confession or lacerating self-examination, but achieves instead a nearly perfect three way balance between a beautiful location, a qualified projection of another's thoughts, and the narrator's own undecidedness about his father's state of mind and comfort; it's a skillfully arranged scenario where a complex interaction of detail and perception are conveyed in language that presents the dueling impressions of exterior beauty and psychic restlessness.

Beyond that, of course, is the perennial mind/body split, voiced in terms of whether a person of diminished capacity is getting the most for their money as they are situated in a beautiful clime, during a perfect day. Nature, though, cares nothing of our aesthetic situation, in fact does not think at all and merely exists as ceaseless churning process, a notion that comes back to us at the end of our contemplation that despite our desires that our mothers, fathers, sons and daughters and, perhaps ourselves, live forever, in memory if not monument, we are mortal and part of the natural process we want to tame with vacation and leisure time, and that the clock is always running out.

The birds-of-paradise,

though mute and flightless, still preen in the breeze.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

CONAN O'BRIEN IS LAME!

delivery, timing or punchlines in the decade plus he hosted Late Night; there was an unsettling, not endearing nervousness about the man's manner (as opposed to style) in front of an audience, and he always made think of the one funny friend you have who thinks he can be a comedian. Yes, you know the punchline, the night your friend signs up at local comedy club amateur night, he breaks out in flop sweat, his topics conflate with one another like unruly schools of fish, his tongue seems to swell, his twitchy delivery is one click away from a sobbing breakdown.

delivery, timing or punchlines in the decade plus he hosted Late Night; there was an unsettling, not endearing nervousness about the man's manner (as opposed to style) in front of an audience, and he always made think of the one funny friend you have who thinks he can be a comedian. Yes, you know the punchline, the night your friend signs up at local comedy club amateur night, he breaks out in flop sweat, his topics conflate with one another like unruly schools of fish, his tongue seems to swell, his twitchy delivery is one click away from a sobbing breakdown.At his best, he seemed like he was rehearsing his ad libs in front of the bathroom mirror; at his worst he looked painfully ill-at-ease, often times casting a sidelong glance that made him appear like a rushing pedestrian trying to catch his profile in a store window. I would say good riddance, of course, but it's only a matter of time before Conan O'Brien sets up shot on another outlet, Fox most likely, and the likes of us looking for something to gaze upon while sleep descends on not quickly enough will have to rush past this over paid stiff's limp humor. To make matters less appealing, we'll have to pass the crusty walls of Lenoland on the way to catch Letterman's usually sprite monologue. One may avoid the whole ordeal, to be sure,by going to bed early; sleep has never seemed more attractive.

Monday, January 18, 2010

Mummified

that poet Charles Harper Webb seemed to be on a creaky anti-West riff, using the anecdote

as reason enough to rehash a favorite harangue. There was a further suggestion that since the poem is a critique of Western technology strip-mining a culture for the sake of economic expansion, Webb wouldn't be inclined to criticize Egyptian history. Their record, it was asserted, wasn't Edenic and absent of cruel events. Had I came across the sentence that he had, I too would have been struck, surely, but the irony of the fact--white people converting human corpses into fossil fuel--and would have been motivated to write my own mediation on the severely negative side of Imperialism. His concern wasn't whether Egyptian history was noble or ignoble, but that European exploration into the area was intended not to learn but to discover exploitable resources. What he gets at, his intent and success, I think,is that the mentality is a pervasive attitude in the invading culture, and that the psychology extends to a narrowly set pragmatism; short of coal and timber, need to save money. Blimey, burn these bandaged cadavers, there not doing any good just laying around as they are. The fault with Cameron's visually magnificent Avatar , is that it relies on tropes that are too obvious, especially on the Pocahontas / John Smith tale. Webb, on the other hand, is riffing on an historical fact, and provides a provocative argument that it's not an isolated instance. I don't think he's anymore anti-West than , say, Jonathan Swift or , say, H.L.Mencken, two writers we praise for their critical eye and caustic wit, as well as their willingness to speak an unruly version of Truth to whatever gathered assemblage of thugs happen, at the moment, to constitute Power. You could say that Webb is a satirist in someway, a wiseacre, but whatever he is in spirit, he still notices how things that are said clash with things that are done, and that, like George Carlin, he has a willingness to push codified interpretations to the point where they become absurd. He is a poet, I think, who is keen on exposing contradictions and revealing the lies and embedded evasions we use to ease ourselves through the daily dose of cognitive dissonance.

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Poems by Galway Kinnell and Larry Leavis

The difference is that his poems have a mood and a destination he seeks in his inclusion of every day things and events and his self-conscious interactions with them. All the choice ironies he writes in this poem, poem are fluid and presented with a rhythm that combines of someone recalling a recent set of experiences and sensing the arrangement of the details. It's not unlike watching someone unpack boxes in a room of empty shelves, arranging the books and bric a brac in positions that highlight priority of detail. --

SHEFFIELD GHAZAL 4: DRIVING WEST

A tractor-trailer carrying two dozen crushed automobiles overtakes a tractor-trailer carrying a dozen new.

Oil is a form of waiting.

The internal combustion engine converts the stasis of millennia into motion.

Cars howl on rain-wetted roads.

Airplanes rise through the downpour and throw us through the blue sky.

The idea of the airplane subverts earthly life.

Computers can deliver nuclear explosions to precisely anywhere on earth.

A lightning bolt is made entirely of error.

Erratic Mercurys and errant Cavaliers roam the highways.

A girl puts her head on a boy's shoulder; they are driving west.

The windshield wipers wipe, homesickness one way, wanderlust the other, back and forth.

This happened to your father and to you, Galway -- sick to stay, longing to come up against the ends of the earth, and climb over.

All speak of the contradictions of travel and the false hopes that lie in the speed and distance one can personally attain. As with his father, Kinnell finds he can not travel out of his own skin or his awareness of who he is and suggests that his attempts to out pace his demons merely fed their flame.

______________________

Normally I dislike poems that use poetry or the fact that the writer is a poet as their subject matter because it smacks of a chronic elitism that kills the urge to read poetry at all, but Larry Levis in the poem below attends to the task with humor and a willingness to let the air of out of the practitioner;s inflated sense of importance. He is of the mind that poems have to "hit the bricks", get road tested where people live and work. What makes his writing remarkable is his ability to be straight forward without being literal minded.

The Poem You Asked For

by Larry Levis

My poem would eat nothing.

I tried giving it water

but it said no,

worrying me.

Day after day,

I held it up to the llight,

turning it over,

but it only pressed its lips

more tightly together.

It grew sullen, like a toad

through with being teased.

I offered it money,

my clothes, my car with a full tank.

But the poem stared at the floor.

Finally I cupped it in

my hands, and carried it gently

out into the soft air, into the

evening traffic, wondering how

to end things between us.

For now it had begun breathing,

putting on more and

more hard rings of flesh.

And the poem demanded the food,

it drank up all the water,

beat me and took my money,

tore the faded clothes

off my back,

said Shit,

and walked slowly away,

slicking its hair down.

Said it was going

over to your place.

Poets often enough try to use idiomatic language with the intention of using the vernacular to suggest dimensions of significance only a select priesthood of poets can decipher, if only barely; too often all the reader gets is a lugubrious meandering in the mother tongue of something that cannot decide what it wants to be. I suspect many take themselves to be latter day Ashberys or keepers of the Language Poetry practical/critical attack, but this would a defensive reflex, I think, a wall around an ego that cannot concede that it's owner has written a body of poems that mistake being dense with density. Dense merely means impenetrable, which means nothing , ideas in this case, get or get out. Density is somewhat more of a compliment, implying, as I sense it, that there lies therein a series of perception and interestingly worded ideas that cling to solid images in a lean, subtle, nearly invisible way--intellection and detail find a perfect fit--that one can draw series of readings from the work, if not a final verdict. Leavis shows that it's possible to elude having to explain yourself and be suggetively vague to intent without sacrificing the illuminated surface of the poem.

Sunday, January 10, 2010

Rock and Roll

Truthfully, I had to walk away from a conversation in late December that rock and roll is was dead as a boot; Fifty somethings like myself have the feeling that last bit of authenticity ended as we came into our late twenties and had replaced avocations with careers. I’m just tired of anyone declaring whole art forms as “deceased” merely because they’ve gotten older; rock and roll seems healthy to me, as it goes, and however large a segment of the marketplace it holds , those who play it and those who listen to it, young and not so young, think the music is alive and, well, kicking ass. The complaints come down to this, The Fall from Grace; the Garden of Eden was so much nicer before the corporate snakes moved in and loused it up for everyone. Regardless of musical terms and pseudo terms that are tossed about like throw rugs over a lumpy assertion, is the kind of junior-college cafeteria table thumping that is demonstrably empty of content. Reading any good history of rock and roll music will have the music develop along side the growth of an industry that started recording and distributing increasingly diverse kinds of music in order to widen market shares. The hand of the business man, the soul of the capitalist machine has always been in and around the heart of rock and roll: every great rock and roll genius, every jazz master, each blues innovator has the basic human desire to get paid. Suffice to say that some we see as suffering poets whose travails avail them of images that deepen our sense of shared humanity see themselves still as human beings who require the means to pay for their needs and finance their wants, like the rest of us. There has always been a market place where the music is played, heard, bought and sold--and like everything in these last months, the marketplace has changed, become bigger, more diffuse with new music, and new technologies. Some of us are vaguely, and snottily mournful for an era when only the music mattered, and something inside me pines for that innocence as well, but innocence is the same currency as naïveté, and consciously arguing that the way I formerly perceived the world was the way it actually worked would be an exorcise in ignorance, as in the willful choice to ignore available facts that are contrary to a paradigm that's sinking into its loosely packed foundation. Again, it's hard to discern the line naysayers want to peruse, other than prove that he's an amateur Mencken, a pundit without platform, sans portfolio. It's my suspicion that for the typical young music listener now, this is the Eden they expect never to end, which means that it’s the best time in the world for rock and roll for some mass of folks out there.

Friday, January 8, 2010

Against Rhyme 2

"Isn't it interesting that so much instantly forgettable poetry is written by poets who disparage any form of rhyme!" I am vain enough to assume she meant me in her offering, to which I was also vain enough to respond to. Likely her response will mention that she didn't name me at all, add a couple of more indirect digs, after which we can expect that conversation to become stony silence or snarky round robin. All the same, here's my response, and the last I'll bother this blog with on this subject.

Much of my poetry is forgettable , yes, but much of it is good, I think, as I've been at this craft, free-verse style, for a very long time. The quality of my output, I believe , is on a par with any other good yet minor (league) poet with an ear for music who continues to hone their skills, is mostly in relative anonymity; grand slams, hits, near misses, strike outs, belabored performances, all of them in mostly equal abundance. My poetry, if I happen to be your unnamed example, isn't the point of comparison, though, and is largely irrelevant to what I was addressing. I would challenge anyone to produce something I've written, here or elsewhere, where I insisted my writing in general as an example anyone should follow; my claims for my style are modest. Let us just say that I like the way I write prose and that my style in poetry has evolved over some 40 plus years and that I believe there's been some improvement in quality. The point in the original was, and remains, that rhyming in the current time is archaic technique that is at odds with the zeitgeist and expressed the idea that it too often sounds strained, false and little more than a demonstration of one's facility with a technique that calls attention to itself rather too much.

Eliot, of course, could compose rhymes (as opposed to "construct") that were fluid and musical and never far from the sound of the spoken voice. For all his erudition , he could write an abstract, fragmented verse in a clear and plain vernacular, and was able, as well, to extend his phrase of the voice , not of the metronome, a guiding aesthetic during his period. Masterful as his rhyme schemes were, however, Eliot is generally regarded as someone who could mix his techniques, balancing free verse and the metered form.

This was part of his genius, and that sort of genius , in the twentieth century as regards an exclusive rhyming technique, is rare, rare, rare. None of this, though, is to insist that there is no place for rhyming--the skilled hand can employ it when it makes musical sense, when it is effective service to a perception and does not announce itself , as so many latter day New Formalist poets do when they write their elaborations. The great poems in English of the 20Th century are not rhymed; the poets of the last hundred years or so have sought less to mimic the argued perfections of ancient standards and sought rather to seek individual accommodation with a general conception of the human voice as it speaks. The heavens and the earth are less the things to be pondered through rhetorical skeins that imply an extra-human dimension than the are things we see and speak of in terms of our own experience, the subjective passing through the general conception of everyday life.

Wednesday, January 6, 2010

Against Rhyme

Just because something rhymes and has regimented meter doesn't, by default, make it a poem. We would generally think agree that a poem is , in some sense , a heightened speech that seeks to get at perception, sensation, and psychological states that are problematic for standard prose writing, and that , broadly speaking, the writing that qualifies for those qualities, vague as they are, ought not to be sentimental, conventional, sing-songy, prone to cliche, platitude , scoldings, lectures, or inanely obvious moralizing.

Rhyming, a condition that about dominated all poetic technique until relatively recently in written history, has about been exploited to the degree that it is nearly exhausted . A contemporary audience, desiring a more intriguing vocabulary to discuss and describe the experience of the individual in a culture that is accelerated and quantified and subdivided among a host of meaningless disciplines, wants that discussion to be in a parlance, a rhythm, a cadence and verve that is recognizably of the modern time that typifies the way we address our experiences, and yet has the embedded genius to last decades beyond it's writing.

The art continues as it always has, it changes as the language has, it's pitches and dictions have taken on the twists of the spoken language and forges a unique set of voices that keep the language fresh, relevant, alive. It might well have to do with the fact that the feeling of experience can no longer be contained and convincingly resolved with the now-formula ironies a precise formula compels you to reach; two world wars and the use of nuclear weapons has pretty much undercut the chiming resonance formalistic poems present us; they sound false and eager to smooth away the tragic, the gritty, the sad, the plainly inexplicable conditions of everyday life with a grandiose , over determined orchestration of sounds that are meant, I suppose, to convince you that beauty is most important overall and that petty miseries and small joys are of no consequence. It seems nothing less than a mirror of the conceit of organized Christianity that God has a purpose for this world and that we must accept his will, as small laces in a complex weave. It's about surrender, actually, but it would be the case, rather, that enough history has culminated so recently regarding the disasters of absolutist philosophies that the taste, collectively, has preferred the colloquial to the grand, the open ended to the determined resolution, being-in-the-moment rather than controlling the agenda.Syllabic convolutions, pretty as they sound, are just that, pretty sounds, not the voice of Higher Authority.

The language changes; that's how it stays viable as way of making ourselves understood. Poetry changes; that's the way we keep ourselves interested in testing the limits of our imaginations. Poetry is an active thing, done in real time, in the present period. It is not an art consigned to being little more than duplications of what was done before, endlessly before, forms leeched of all vitality and allure.

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

This tug has a kick

Nothing comes into being until "you" see it and confront it, do something with it, and then walk away from it, with a narrator trying just a bit too hard to convince the reader that "you" have been changed, or encountered an irony that is , for the moment, invisible and not felt.

Tuggin' has the good graces of being short and not epic , and what we get is a breathless stream that has the magical , exhilarating feel of an excited witness recounting to the the protagonist just how incredible the previous adventure was.

Miller does interesting things with letting things bump into one another, step on each other's toes, of allowing one idea to intrude upon the other; there is the the feeling that there is only so much time to set the seen, establish the winter game in the cold snow, and to emphasise how fast the fun comes at you and how abruptly a tragedy can occur.

Then the steel-.

hearted tug as the truck started up

again, as your shoulders yanked

to just short of snapping. And if

you held on, your time was up

as the driver fishtailed and cast

you across the covered concrete

to bury you in a six foot bank

of snow, everyone cackling, blood

electric, all the pieces of your face

inches away from the hydrant

you wouldn't see till spring.

Action, jerks of a truck, rules of the game, landing in a snow bank , just missing the unforgiving fire hydrant that other wise might have been unseen and out of mind until the spring thaw; this is a a lot of information to get across, and Miller writing seems something like a vivid slide show with quick witted captions underscoring both fun and the danger.

He does something else as well, with the simple mention of the fire hydrant, evoked in a Frost-like terseness; it's a perfect image to end on, some still life that's seasonal and scenic, suitable for a greeting card, but which also reflects back to the "you" that dominates the action; I sense a stunned realization that someone could have been seriously hurt, perhaps killed. Nicely done, effective, fast, visual.

Sunday, January 3, 2010

A meditation for the New Year

harangues. I have no intention of becoming divorced from the one thing, writing, that has been the only thing that I've continually well. I might plug my other hobby that I've gotten more involved with , an activity that fills the time various searches and scannings from different job sites , playing blues harmonica. I video taped myself improvising over instrumental blues tracks, and I have to say, nearly blushing, that I've gotten pretty good. You can find those bits of funky squawking on YouTube, under the user name TheoBurke. There is a link in the blogroll . But the issue at hand is getting into the writing groove again, to keep my mind alive and to perhaps gain a sliver of self esteem and relief, if only to believe that my brain isn't dead and that I will be employed again, in a job I like, and that things all around, for all people, will get better by measurable , noticeable degrees. Well yeah, you guessed it by this point, I am writing this just to see the page fill up with words, and there is a measure of trying to hype myself to the tasks at hand. About being laid off, it must said that I am in good company. There's an understandable tendency to allow one's psyche move toward the dangerous intersection of Fear and Dread, but all things being equal in this world, there is the faith that we will all come through these strange days more or less in one piece. The family, friends, and general fellowship have reminded me when I needed to hear it that there somethings worth pushing on for, that there are things in this life that make life a joyous thing despite the recent set backs many of us have encountered. We will endure, we will thrive, we will go through the changes. Yes, I know, it's all that strained optimistic that clouds many a forecast for the New Year. I look at this way, it can't help but be better than what we've had before. One day at a time, I do the thing that's in front of me, I do the next indicated thing. I type, I write, I live, and that's a good thing, an irreplaceable thing.

Friday, January 1, 2010

second notes for the new decade

Poetry works in many ways, but so does criticism, and a pragmatics of interpretation is the most useful way for me to make a poet's work something other than another useless art object whose maker adhered to someone else's rules. My gripe is a constant one, that each succeeding school of thought on what poets should be doing are too often reductionist and dismissive of what has been done prior. This isn't criticism, it's polemics, contrary to my notion that what really matters in close readings is the attempt to determine whether and why poems work successfully as a way of quantifying experience and perception in a resonating style.

First notes for the decade

but the enemies of the common good love to be discounted; they are well aware that we love to be entertained while we have our hot buttons pushed, and that there far too many Americans with the right to vote who love nothing better than taking conspicuous buffoons seriously.We shouldn't dismiss the idea that Palin, Limbaugh , Beck or, choke, Ted Nugent can become President. The electorate twice elected GW Bush and a host of other fringe-clinging hard righters, a combination that has done the country no good favor.The GOP and the like understand how to work The Big Lie, and have shown a genius at manipulating a general discontent among voters, convincing them again and yet again to vote against their interest. We would do well not to dismiss the above list and stay hard at the fight. The thousands who've shown up at Tea Bag rallies convinces me that there's still a festering, hateful insanity out there; it is no longer at the fringe and has, in fact, metastasized to the center. The Right Wing Noise Machine is louder than it's ever been. We have to make noise of our own and take over the conversation.

but the enemies of the common good love to be discounted; they are well aware that we love to be entertained while we have our hot buttons pushed, and that there far too many Americans with the right to vote who love nothing better than taking conspicuous buffoons seriously.We shouldn't dismiss the idea that Palin, Limbaugh , Beck or, choke, Ted Nugent can become President. The electorate twice elected GW Bush and a host of other fringe-clinging hard righters, a combination that has done the country no good favor.The GOP and the like understand how to work The Big Lie, and have shown a genius at manipulating a general discontent among voters, convincing them again and yet again to vote against their interest. We would do well not to dismiss the above list and stay hard at the fight. The thousands who've shown up at Tea Bag rallies convinces me that there's still a festering, hateful insanity out there; it is no longer at the fringe and has, in fact, metastasized to the center. The Right Wing Noise Machine is louder than it's ever been. We have to make noise of our own and take over the conversation._________________________________

Philanthropist Ruth Lilly has passed away, and there's an increase in the rumbling and grousing about the $100,000,000 endowment she gifted the Chicago-based Poetry Foundation with.It seems that if you want to kill an art form you truly love, give it's practitioners a lot of money to make sense out of. Poetry is such a fractured terrain in terms of techniques, schools, aesthetics and, shall we say, severe differences as to how to see life , that Ruth Lilly's gift was bound to create controversy and resentment; poets are picayune as it is with the meager resources available to them. I'm half way surprised that there hasn't been a blood letting over the funds.Still, I have to say that the Poetry Foundation were as deserving as anything in existence; I was fairly impressed by the fact that they never lowered their editorial standards by publishing one of Lilly's allegedly substandard submissions to Poetry Magazine. Whoring for an endowment they were not.

______________________________

I took a Facebook quiz that would tell me what famous film director I would be, and the answer, revealed after answer some insipid movie related multiple choice questions, was that I was Stanley Kubrick.I have never liked this man's movies. Impressive, yes, but for the most part I think he's all gesture, no story. He was more in love with the allegory than with the story the device was supposed to serve.I might add that Martin Scorsese shares many of the flaws with Kubrick, the bulk be of them preferring spectacle to a plausible and compelling narrative line. The difference, I think, is that Scorsese doesn't take a long time between pestering the world with his lack taste. The would have been one attribute from Kubrick he could have benefited both him and ourselves. I suspect there were nothing but superstar names in the roster of results the quiz created bothered to assemble; obvious choices, me thinks. Clint Eastwood, The Coen Brothers, Michael Mann, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, Ridley Scott, Chris Nolan, Walter Hill, Sam Rami, Guillermo Del Torro, John Huston, Woody Allen, Wes Anderson, Jim Jarmasch, Quinten Tarantino, Sam Fuller, Don Siegel, now there are some names I wouldn't mind being my "inner director".

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

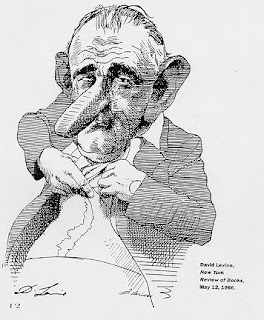

David Levine, RIP

David Levine,very likey the most important caricaturists of the 20Th century, has passed away at the age of 83. Whether his target was Lyndon Johnson,Richard Nixon , Henry Kissinger or Bill Clinton, Levine took an unkind eye to the liars, scallywags and overachieving glory seekers who managed to make the world into a trash-strewn playpen. He showed them them not as extraordinary personalities but rather as chronic sufferers of delusion. Bad haircuts, unshaven jowls, necks that couldn't quite fit into the necks of their assigned shirts, Levine saw these power elitists as strange and difficult creatures who looked and sounded sane , but who seemed malformed and amoral on closer inspection. His acid-etched pen and inks were long a tonic in the middle of many a meandering political controversy,and one wonders where such clarity and moral outrage might come from next. Let's hope we get luck.

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Holmes gets all twisted

Monday, December 21, 2009

More notes on Charlotte Boulay's "planting daffodils"

This is a strong poem, I think, and I don't think there's a false or strained remark or move anywhere in it. The language is unpretentious without being self-consciously barren as, say, David Mamet's or Paul Auster's poems can be, and her elisions , the pause and unspoken link between the imaginative (Juliet) and the material (the garden in fall) is done with just enough spacing to surprise a reader with the association. The connections between them are presented well--there's no sense in the images being overdressed for the occasion, so to speak--and I rather like the darker implication about human vanity being under-addressed, almost not at all, but implicit all the same. It gives you the effect of a delayed shock of recognition.It's wise of her to avoid as well the mention of Easter.This poem within the scope of what man imagines and what man must actually contend with. The context is broader and the inference is wider as a result, and the reader not interested in particular religious references aren't excluded . Boulay seeks a wider empathy.

The whole issue as to what makes for a "moving poem" is as subjective as what the best ice cream flavor is. The distinguishing these differences in taste are what makes discussing poems , at times, a great pleasure. As a poem, "planting daffodils" is a lyric , analogous to music, and there is something in the sound of the words and the spaces between the images they've formed that gives me a clue to several ideas that are tangible yet beneath the surface of what the poem describes; the art of what was almost said. This poem is a useful illustration of how our concepts of life and death are layered in sets of metaphors and analogies that contrast our routine lives with our idealizations, and warns, at the margins, that we will be surprised, shocked and saddened at the end if we think we've gained control of our fate beyond our final day.

Saturday, December 19, 2009

Dulled

So many poems have come our way concerning people who are dead, dying , grievously ill or otherwise three-sheeted to states that lack a pulse. This would be depressing normally, but it 's interesting to witness how the writers manage to obfuscate , obscure and botch a subject. A sudden death is confusing and I understand the attempt to write one's way from a mire conflicting emotion, but there is , often times, only more confusion. Rather than being made aware of the experience in phrases that can unmistakeably convey emotion and irony that can occur in the midst of the psychic turmoil, we are only witnesses to someone's inarticulate graspings towards a verbal effect. It's wearying to come away from a poem convinced not by the by the sentiment , but only by certainity that the writer couldn't get across a difficult set of ideas. The problem maybe , at times, that the notions were still forming; even in an art where obvious meanings are not required, there still needs to be a tangible set of figures one has considered and crafted with which a plausible surrendering of disbelief is possible.As with the fallen who are being addressed, directly or by way of intensely crowded example, the poets who've braved the page and revealed their dedications don't appear eager to really discuss anything; imagery,allusion, archaic and grating coinages emerge and make the subject disappear under the weight of description, which may be the hidden strategy after all. There is nothing less than the creation of distance from the heated stew of unresolved tension; compare this event to other things and eventually the original idea is lost , not to return to our mind. For the time being at least...

Rosenthal's "Morophine", while not dealing with a fatality, prefers jumping from one image, metaphor, simile to the other instead of establishing a series of ideas through the imagery to bring us to a perception a reader would not otherwise have had. It begins nicely enough, concretely, but quickly and seeming to plan it is lost in a parade that seems less a poem than devices gone amok:

The window to this world opened again

as the drips slowed, and she became

whippy as a sheet of glass improperly

annealed, ready to smash at any

indefinite touch in a whining matrix

of stresses,the bed frame a museum box

where she lay, encased as a mummified

kestrel tailed with a fleece of fetid cloth

laid out by the mongoose (pharaoh's rat)

cradled in the nook of a dead arm,

and her eyes were intensified as soup

with beef bouillon and parsnip, potato,

celery ends, the candor of bread and butter

to swallow the fact of what happened.

Different ideas come to me, none related to what Rosenthal had in mind; I am thinking more of the Clampitts arriving in Beverly Hills in an old truck crammed with every gougedand dented piece of property they ever bought through the Sears Roebuck catalogue, the toys in many an old cartoon who come alive when the shopkeeper leaves for the night, a bargain table full of sundry used merchandise, slightly worn, marked down . The succession of metaphors is overdone, and the idea --that there is a human need,it appears, to numb and distance ourselves from the unfiltered sensations of both the worlds we have both in and outside our head, and that one desires to be delivered by means greater than themselves to an plateau where the material stuff matters not--is ironically mummified by Rosenthal's desire to make this brief verse vivid. This is a baroque diorama, a box of strained effects, without the lyric imperative. It's a noise maker only, static and crackle.

Monday, December 14, 2009

Artificial, yes. Intelligent, no.

Salon has started a rather fine film section in it's redesign, and it was a surprise to see Chicago Reader movie critic Jonathan Rosenbaum highlighted in a brief piece defending Steven Spielberg's maligned sci-fi meditation on the human soul, A.I.Artificial Intelligence. His defense of the feature , brave as it is, has the benefit of being a pithy:

Reading it simply as a Spielberg film, as most detractors do, or even trying to read it simply as a Kubrick film, is a pretty futile exercise with limited rewards, even though the fingerprints of both directors are all over it. Seeing it as a perpetually unresolved dialectic between Kubrick and Spielberg starts to yield a complicated kind of sense -- an ambiguity where the bleakest pessimism and the most ecstatic kind of feel-good enchantment swiftly alternate and even occasionally blend, not to mention a far more enriching experience, however troubling and unresolved. As a profound meditation on the difference between what's human and what isn't, it also constitutes one of the best allegories about cinema that I know.

I am glad someone thought this was a good movie. I had the good fortune to take a couple film courses with Jonathan Rosenbaum in the seventies when he was a visiting film lecturer in UC San Diego's Visual Arts Department. The topic of one class, Paranoia in Films, was an especially engaging, if diffusely defined course, and it was of particular interest that the required text for the course was Gravity's Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon, from which Mr. Rosenbaum would bestow cryptic quotes from the book like "God is the original conspiracy theory" while showing acutely observed studies in monomania such as Nick Ray's Bigger than Life. That film in particular was apt for a course in paranoia on film, as it dealt with a meek school teacher's growing dependence of a mood altering medicine (cortisone) that converted into an arrogant, edgy, lunatic who needed eventually to be placed in a straight jacket. The print Rosenbaum received for the class wasn't the theatrical print he expected, but rather the cropped version, intended for television screens, where much of the image was cut away and the focus was on the talking heads. Viewing a tightly contained James Mason screaming larger than life on a large auditorium screen made you feel like you were watching someone trying to escape from a shrinking glass box. Paranoid indeed.

It's with this back story that I understand his appreciation of A.I.:Artificial Intelligence, but where he sees a brave vision from Steven Spielberg in the way he attempts to sort through the ways technology threatens to blur and eventually erase the distinctions between human and android programming--the eventual point was that both these creations are subject to a hard wiring that needs to bond with others as a defense against the lurking solitude--but it remains for me a vague, grandstanding mess. The buzz was that this was intended as the last film Stanley Kubrick was to make but never got to, and that Spielberg had gained access to the notes and developed his own ideas about how to flesh out, so to speak, the bare premise. Kubrick , is not the best person to pick if you're in the market for a useful idea for a film; more than a few of us have felt that the late director's reputation was inflated beyond sane justification, a man who could indeed shoot an engrossing sequence but was ill at ease to explain what thinking lay behind his imagery. It was a matter of monumental style in Kubrick's films, and he's lucky enough to make a hand ful of movies that haven't had their reputations collapse after their initial release and the wave of awestruck reviews.

His final movie, Eyes Wide Shut, was as pompous and preposterous a botched project as anything Ed Wood had made; you suspect that he had actually died before he had a chance to repair the raw feed in post production. Even the director's skill for making capable actors appear like sleepwalkers wasn't enough to calm the antsy Tom Cruise; he remains within his emotional range as an over-eyed wind-up toy. AI,in kind, was a half a bad idea from Kubrick's mind, was was reason enough for Spielberg to pour on the effects, flash the lights, go crazy with the colors, with abrupt and unconsidered cuts between broad humor, family hour sweetness and uncorked violence and villainy. The last set of clauses sound like a Coen Brothers movie, sure, but the Coens have a tone that runs through through their vexing genre variations and character studies; there are links, there are connections, there are matters in the frames that can be discussed, debated, but which are very tangibly present in the movie. Spielberg is muscle, flash, loud noises; his idea of subtext is a Cliffs Notes of discussion points--what morality play that can be discerned operates only on the surface, and it is when this happens--as it does all though this messy, ill-lit narrative--that you realize what button-pushing schlock meister the director really is. The whole A.I. enterprise comes off like that horribly cropped scene of James Mason yelling on an auditorium screen. Nothing at all fits the slim premise.

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Best Books of the Decade

But we are here, ready or not for the next decade, ready or not in one's attempts to secure a sound employment ( too much detail, perhaps, but I was laid off my job last week, but I'm in noble company). My best guess to that matter is that we are ready; there have been some terrific books written over the last ten years , some brilliant writing, intriguing tales, illuminating accounts of emotion and fancy, all of which serves the central purpose of literature, to help us think about ourselves in the world.

These books have kept me out of the vacuum of merely sitting in front of a computer grazing off the headlines --they have kept me engaged with the world for the last ten years and have given me ample reason to talk to old friends and make new ones. We have something to talk about, and that seems to be the point of reading books and sharing what one enjoys with others; books are the grounds through which our different lives find a common set of metaphors , through which we can discuss surmount of differences and frame our similarities.

My best books of the Last Decade. These remarks, of course, are culled from previously posted reviews.

My Vocabulary Did this To Me

poems by Jack Spicer

Spicer is an interesting poet on several levels, all of them deep and rich with deposits that reward an earnest dig. He is , I think, on a par with Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams with the interest in grilling the elaborating infrastructure of how we draw or are drawn to specialized conclusions with the use of metaphor, and it is to his particular brilliance as a lyric poet, comparable to Frank O’Hara (a poet Spicer declared he didn’t care for, with O’Hara thinking much the same in kind) that the contradictions, competing desires and unexpected conundrums of investigating one’s verbal stream are made comprehensible to the senses, a joy to the ear. No one, really no one wrote as distinctly as the long obscure Spicer did, and editors Gizzi, Killian and publisher Wesleyan Press are to be thanked for restoring a major American voice to our shared canon.

Bear v. Shark

a novel by Chris Batchelder

Bear V. Shark by Chris Bachelder is post-modern hoot. Don't let the tag "post modern" put you off, because Bachelder gets it exactly right as he skews his target, television and the culture of Total Media Saturation. Bear V.Shark is a great, wild read for anyone who enjoyed Pastoralia or the work of Mark Leyner. There is a vaguely described though loudly trumpeted Big Event forthcoming that's precisely what the title suggests, in a future time when TVs have no off switches and whose soft ware can sense a viewers boredom and flip the channels for them: TVs are everywhere in this world, in the kitchen, the furniture, bus stops, train stations, and in such a society, the idiom of everyday language is subverted by commercial patois and jingles. America, here, is subtly insane and in a constant state of distraction.This is the America that Baudrillard absent mindedly ruminated about, only much funnier, edgier, and smarter in the evisceration

Cosmopolis

a novel by Don DeLillo

Don DeLillo again shows that he's our best novelist of American absurdity with this strange off-kilter comedy that centers around the events of an eventful day in Manhattan. Against a backdrop of raves, a Presidential motorcade, a rock star's funeral, mysterious street demonstrations and the constant, ghostly electronic feed of news of pending financial disaster, a young billionaire asset manager limousines uptown to get a haircut in order to embrace his sense of inevitable, personal apocalypse. DeLillo's writing is outstanding, funny with a cool lyricism, poetic when you least expect it. The brillance here, as with White Noise and especially Mao ll is the way characters seek to reconfigure their metaphors, their assuring base of references , once their world view is rattled and made less authortative by unexplainable events and human quirks. This is semiotics at its best, an erotic activity where DeLillo probes and glides over the surfaces of ideas , notions, theories and their artifacts, things intellectual and material emptied of meaning, purpose. It's a hallmark of DeLillo's mastery of language that he gets that psychic activity that constantly tries to reinfuse the world with meaning and purpose after the constructions are laid bare; Eric, here in this world of commodity trading, which he regards as natural force that he's mastered and control, attempts to reintroduce mystery into the world he is trapped in. He is bored beyond the grave with the results of his luck. His efforts to live dangerously , spontaneously and thus get a perception he hadn't had and perhaps secure a hint of a metaphysical infrastructure that eludes, all turn badly, but for DeLillo's art it's not what is found , discovered, or resolved through the extensions of language, but rather the journey itself, the constant connecting of things with other things in the world; this is the poetry of the human need to make sense of things in the great , invisible state beyond the senses, a negoiation with death. His imagistic tilling of the semiotic field yields the sort of endless irony that makes for the kind of truly subversive comedy, a sort of satire that contains the straining cadences of prophecy. The city, the place where the the hydra-headed strands of commerce, history, technology and government merge in startling combinations of applied power, becomes an amorphous cluster of symbols whose life and vitality come to seem as fragile and short-lived as living matter itself.

The Time of Our Singing

a novel by Richard Powers

This amazing novel by Richard Powers. an ambitious generational tale of an American family with a mixed heritage of African-American and German Jew, and covers the travails, triumphs and tragedies of this family. There are three children, one with a beautiful singing voice who opts for a classical music career, a daughter who becomes involved with the civil rights struggle,and a second brother who, though gifted as well, buries his ambition to bridge the gap between his siblings. Not a perfect novel--sometimes Powers' superb style turns into a list of historical events as a means to convey the sweep of time-- but the central issues of race, identity, culture are handled well within the story. The writing is generous and frequently beautiful, especially at the moments when the description turns to the music. Powers, as well as any one, describes how notes played the right way can make one believe in heaven and the angels who live there.

Frantic Transmissions to and From Los Angeles

a memoir by Kate Braverman

Frantic Transmissions to and From Los Angeles is a memoir, of sorts, about growing up in Los Angeles, and then the eventual moving away from that famously center-less city. Writing in a high poetic and semiotically engaged style that recalls the best writing of Don DeLillo (Mao ll) and Norman Mailer (Miami and the Seize of Chicago), Braverman deftly defines isolated Los Angeles sprawl and puts you in those cloistered, cul-de-sac'd neighborhoods that you drive by on the freeway or pass on the commuter train, those squalid, dissociated blocks of undifferentiated houses and strip malls and store front churches; the prose gets the personal struggle to escape through any means , through art and rage, and this makes Frantic Transmissions not unlike Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, wherein the prodigal son or daughter deigns to move up and away from a home that cannot keep them, with only raw nerve and the transforming elements of art to guide them. What Braverman confronts and writes about with a subtly discerning wit is the struggle of defining the place one calls home, and what roles one is obliged to assume as they continually define their space, their refuge. All through this particularly gripping memoir there is the sheer magic and engulfing power of Braverman's writing; I was fortunate to receive an uncorrected proof of Frantic Transmissions a couple of months ago, and I was knocked out by what I beheld. Sentence upon sentence, metaphor upon simile, analogy upon anecdote, this writing is rhythmic and full of stirring music. There is poetry here that does not overwhelm nor over reach; this is an amazing book, and it is one of the best books about life in Los Angeles , quite easily in the ranks of Nathaniel West, Joan Didion, and John Fante.

HIP:The History

non fiction by John Leland

John Leland's Hip:The History is the sort of book I like to read on the bus, the portentous social study of an indefinite essence that makes the reader of the book appear, well, hip. This is the perfect book for the pop culture obsessive who wonders, indeed worries and frets over the issue as to whether white musicians can become real blues musicians or whether Caucasian jazz musicians have added anything of value to the the jazz canon besides gimmick.

Leland, a reporter for the New York Times, has done his research and brings together the expected doses of cultural anthropology, literature and, of course, music to bear on this sweeping, if unsettled account as to what "hip" is and how it appears to have developed over time. Most importantly he concentrates on the lopsided relationship between black and white, each group borrowing each other's culture and suiting them for their respective needs; in the case of black Americans, rising from a slavery as free people in a racist environment, hip was an an ironic manner, a mode of regarding their existence on the offbeat, a way to keep the put upon psyche within a measure of equilibrium. For the younger white hipsters, in love black music and style, it was an attempt to gain knowledge, authenticity and personal legitimacy through a source that was Other than what a generation felt was their over-privileged and pampered class. Leland's range is admirable and does a remarkable job of advancing his thesis--that the framework of what we consider hip is a way in which both races eye other warily--and is sensitive to the fact that for all the attempts of white artists and their followers to cultivate their own good style from their black influences, the white hipsters is never far from black face minstrelsy. For all the appropriation,experimentation, and varied perversions of black art that has emerged over the decades, there are only a few men and women who've attained the stature of their African American heroes, people who, themselves, were the few among the many.

The Silver Dazzle of the Sun

poems by Paul Dresman

The speakers are shaped by language that accommodates the vastness of region, The West, both as a physical place and collective social construction, looms large in a good deal of the present poems(as it is in Dorn's long lines), and it is the marriage of voice and location that gives the poetry in The Silver Dazzle of the Sun a life that is absent from too much published poetry. The world climbs through the language and appears through deft description fresh as a moment of first perception; style is content, to beg an old question, but it's a worthwhile distinction to make clear. Dresman's work brings us a world of felt experience that can be addressed in useful ways. There are no epistemological quandaries here, no rueful mediations on malformed vowels. There is , though, plenty of wit, anger, flights of lyric speculation, writ with a sure composing hand.There is something of a medley of voices at play in these works, where a terrain on which innumerable generations of have written on emerge in a layered and subtly orchestrated music. The poetics of wonder, rage, joy and sorrow are harnessed with extraordinary skill. Above all else, the poems come from a voice that is speaking to you;

there are moments when the candor and unreticent wit of the writing makes you ponder again the incidents in your own experience that you might not have regarded for years. The poetry is that good.

Big If

a novel by Mark Costello

This is a superb comedy of contemporary American life involving a low-level Secret Service agent who finds she must get reacquainted with her computer-genius brother when she takes a respite from the paranoid turns and twists of her job. This is a book of richly skewed characters doing their best to make sense of their lives. Costello's prose is alive with the things of our life, and is superb at demonstrating the clash between happiness material items promise and the world that denies such rewards. He is the master of setting forth a metaphor and letting it travel through a storyline just beneath the surface, operating silently, almost invisibly, always effectively.

Their father, in the first portion of the book , is a moderate Republican insurance investigator of scholarly reading habits who happens to be a principled atheist. You cannot have both insurance, the practice of placing a monetary remuneration on unavoidable disaster, and assurance, which has religion promising protection from evil and disaster. The children, in turn, assume careers that seem to typify the dualism their father opposed, son Jens becoming a programmer for the Big If on line game for which he writes "monster behavior code" that attempts to outsmart human players and have them meet a hypothetical destruction. Daughter Vi, conversely, becomes a Secret Service agent, schooled in the theory encoded in The Certainties, a set of writings that lays out the details, nuances and psychology of extreme protection. These are world views in collision, and Costellos' prose is quick with the telling detail,the flashing insight, the cutting remark. On view in Big If are different models on which characters try to contain , control, or explain the relentless capriciousness of Life as it unfolds, constructs through which characters and the country and culture they serve can feel empowered to control their fate in a meaningful universe. The punchline is that Life goes on anyway, with it's fluctuating, undulating, chaotic dynamics that only occasionally seem to fall into place. Costello wrests a subtle comedy of manners from the small failures of anyone's world view to suitably make their existence unproblematic. This is a family comedy on a par with The Wapshot Chronicle, but in an America that is suddenly global, an air that makes even the most familiar things seem alien and fantastic. Costello is a modern master, and fans of White Noise and The Corrections will enjoy the emergence of a master.

It's Go In Horizontal: Selected Poems 1974-2006

poems by Leslie Scalapino

Laying out a poem like it were a trail of bread crumbs a reader would to the bigger feast of The Point Being Made is not how writer Leslie Scalapino writes. As we find ourselves in a time when the popular idea of the poet and their work they compose seems slanted toward the lightly likable Billy Collins and others witing poems that can be grasped, shared, written out in a fine hand on perfumed paper and preserved between the leaves of a dictionary of quotations. Scalapino requires not the casual gaze but the harder view, the more inquisitive eye. Scalapino brings a refreshing complexity to her work, a sanguine yet inquisitive intelligence that is restless and dissatisfied with the seemingly authorized narrative styles poets are expected to frame their ideas with. The framing, so to speak, is as much the subject in her poems and prose, and the attending effort to interrogate the methods one codifies perception to the exclusion of details not fitting a convenient structure, Leslie Scalapino has produced a body of work of rare and admirable discipline; the writing is a test of the limits of generic representation.Her work as well is an inquiry in how we might exist without them. In as series of over nineteen books over published since the seventies, she has been one of the most interesting poets working , an earnest inquisitor of consciousness and form blurring and distorting the boundaries that keep poetry, prose, fiction and auto biography apart.It's Go in Horizontal is a cogent selection from three decades of writing. The distinction blurring is not a project originating with her, but there is in Scalapino's work the sense of a single voice rather than expected "car radio effect", the audio equivalent of Burrough's cut up method that would make a piece resemble an AM dial being moved up and down a distorted, static-laden frequency. Leslie Scalapino's writing is one voice at different pitches responding to an intelligence aware of how it codes and decodes an object of perception. The work is fascinating , interrogations that wrestle with the act of witnessing.

The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan

poems by Ted Berrigan

It's not enough that we have the same first name and the same Irish second initial, my attraction to Berrigan's poems was the rather unbelligerent way he ignored the constricting formalities in poetry and rendered something of a record of his thoughts unspooling as he walked through the neighborhood or went about his tasks. "Where Will I Wander" is the title of a recent John Ashbery volume, and it might well be an apt description of Berrigan's style; shambling, personal, messy, yet able to draw out the sublime phrase or the extended insight from the myriad places his stanzas and line shifts would land on. The world radiated a magic and energy well enough without the poet's talents for making essences clear to an audience needing to know something more about what lies behind the veil, and Berrigan's gift were his personable conflations of cartoon logic, antic flights of lyric waxing, and darkest hour reflection , a poetry which, at it's best, seemed less a poem than it did a monologue from someone already aware that their world was extraordinary and that their task was to record one's ongoing incomprehension of the why of the invisible world.

The Age of Huts

poems by Ron Silliman

The Age of Huts brings together several books he's published as a long standing project. It makes for alternately exhilarating and exasperating reading. Those who stay with Silliman and his task are rewarded with what is really the most thorough on going examination of the American vernacular since William Carlos Williams composed and assembled his central epic poem Paterson in 1963. Silliman’s is the language of a place, and there is a logic as the streams and eddies of unassigned sentences the blended variations at once rich, dissonant.

The Time of Our Singing

a novel by Richard Powers

This is an amazing novel byRichard Powers. an ambitious generational tale of an American family with a mixed heritage of African-American and German Jew, and covers the travails, triumphs and tragedies of this family. There are three children, one with a beautiful singing voice who opts for a classical music career, a daughter who becomes involved with the civil rights struggle,and a second brother who, though gifted as well, buries his ambition to bridge the gap between his siblings. Not a perfect novel--sometimes Powers' superb style turns into a list of historical events as a means to convey the sweep of time-- but the central issues of race, identity, culture are handled well within the story. The writing is generous and frequently beautiful, especially at the moments when the description turns to the music. Powers, as well as any one, describes how notes played the right way can make one believe in heaven and the angels who live there.

The Plot Against America

a novel by Philip Roth

Novelist Philip Roth, always a spiky and unpredictable story teller, creates an alternative history for America, a fascinating and troubling fantasy of "what if": Charles Lindbergh, aviation hero and Nazi-sympathetic isolationist, is nominated by the Republican Party in the 1940 presidential election, and handily defeats FDR. Using his own family as the center of this fable, Roth has written a novel with the impact of a memoir of hard and terrible times,speaking to how easily a homegrown fascism could take root and grow. The power of Roth's novel lies not only in the impressive historical research he brings to the novel, but especially in how creeping Totalitarian persecution effects the lives of characters who are complex, sympathetic, argumentative. This is not a dry recital of dates, events, names from fading ledgers and indexes, because the novel is a family saga among its several formations, and what Roth has done is highlight a family's struggle between each other and their inner lives while the nation prepares to give in to its worse fears and lay the land for fascism. Several instances -- the family listening the radio during the convention, a hapless father become less powerful in the children's eyes as political forces move against American Jews, the subtly advanced symbolism of the fictional Philip Roth's stamp collection-- gives a reader an vivid accounting of the things that disrupted, destroyed, lost by systematized evil.

The Plot Against America is a masterpiece of the first rank, as relevant as morning headlines, timeless as great literature, qualities that place him, unexpectedly, in the same league with Sinclair Lewis.This is art as a form of truth-telling, of an acute paranoia made comprehensible through a focus of literary skill that gives voice to the unspeakable. Roth was obliviously raised to revere democracy , and this work, tempered by experience and the history of human kind to go wrong and become complicit in evil, sounds off a warning for the reader that is hardly an original thought but meaningful resounds even still: the price of freedom is constant vigilance because the enemies of our rights as citizens are snakes sleeping with one eye open.

The Body Artist

a novel by Don DeLillo

DeLillo is perhaps the best literary novelist we have at this time, which the career-defining masterwork Underworld made clear to his largest readership yet: at the end of all those perfect sentences , sallow images and and long, winding, aching paragraphs is a narrative voice whose intelligence engages the fractured nature of identity in a media-glutted age. The Body Artist has him contracting the narrative concerns to a tight, elliptical 128 pages, where the Joycean impulse to have a private art furnish meaning to grievous experience is preferred over the dead promises of religion and philosophy. What exactly the woman character does with her performance body art, what the point is of her ritualized , obsessed cleansing of her body, is a mystery of DeLilloian cast, but it's evident that we're witnessing to a private ritual whose codes won't reveal themselves, but are intended as a way for the woman to again have a psychic terrain she can inhabit following the sudden and devastating death of her film maker husband. The entrance of the stranger in the cottage turns her aesthetic self-absorption , slowly but inevitably, into a search into her past in order to give her experience meaning, resonance, a project she quite handily ignores until then. The sure unveiling of her psychic life is a haunting literary event. DeLillo's language is crisp, evocative, precise to the mood and his ideas: you envy his flawless grasp of rhythm and diction as these traits simultaneously make the cottage on the cold , lonely coast seem sharp as snap shot, but blurred like old memory, roads and forests in a foggy shroud. A short, haunted masterwork.

Crackpots

a novel by Sara Pritchard

Brief, beautifully written book about an awkward young girl being raised by an eccentric family. Note that there is no child abuse or other hot button stuff engineered in to make the book appeal to the Oprah book clubs, just a humorous and bittersweet novel of a girl, beset with any number of glum circumstances and embarrassments, maturing to a resilient adult with soft irony that gets her through the day. Pritchard is especially fine as prose stylist.

Half Life:Poems

poems by Meghan O'Rourke

Meghan O'Rourke,poetry editor for The Paris Review and a cultural editor for Slate,is also a poet with unique ability to get a nearly intangible notion, an inexlicapable sensation into words. Giving voice to hunch, making the half-idea a textured, tangible thing, hers is a poetry that completes sentences we cannot finish ourselves. Precision and morphological accuracy aren't the point, and the words themselves, the images they create or suggest, are more like strands of half remembered music that is heard and triggers an intense rush of association; any number of image fragments, sounds, scents, bits of sentences, suggestions of seasonal light in a certain place, race and parade through the mind as fast as memory can dredge up the shards and let them loose. Just as fast, they are gone again, the source of quick elation or profound sadness gone; one can quite nearly sense that streaming cluster of associations that make up a large part of your existence rush onward, going around a psychic bend, scattering like blown dust in the larger universes of limitless life. All one is left with is memory of the sudden rush, the flash of clarity, and the rapid loss, the denaturing of one's sense of self in a community where one might have assumed they were solid and autonomous in their style of being, that nothing can upset the steady rhythm of a realized life.

-

The Atlantic a month ago ran a pig-headed bit of snark-slamming prog rock as "The Whitest Music Ever, "a catchy bit of clickbait...